Shabaka Hutchings’ tenor saxophone shows up exactly once on this album. Around 10 minutes before the LP ends, he summons the fierce momentum and sandpapery grit that have powered beloved bands like Sons of Kemet, the Comet Is Coming, and Shabaka and the Ancestors, and helped to make him one of the most celebrated jazz musicians of the past decade. As is usually the case when Shabaka—now billed by first name only—picks up what he has called the “big, loud, shiny horn,” the solo is thrilling. But this brief, incendiary statement carries a special weight in the wake of Shabaka’s announcement—made on New Year’s Day 2023 and clarified that summer—that he would be taking an indefinite hiatus from the tenor and his groups that feature that instrument.

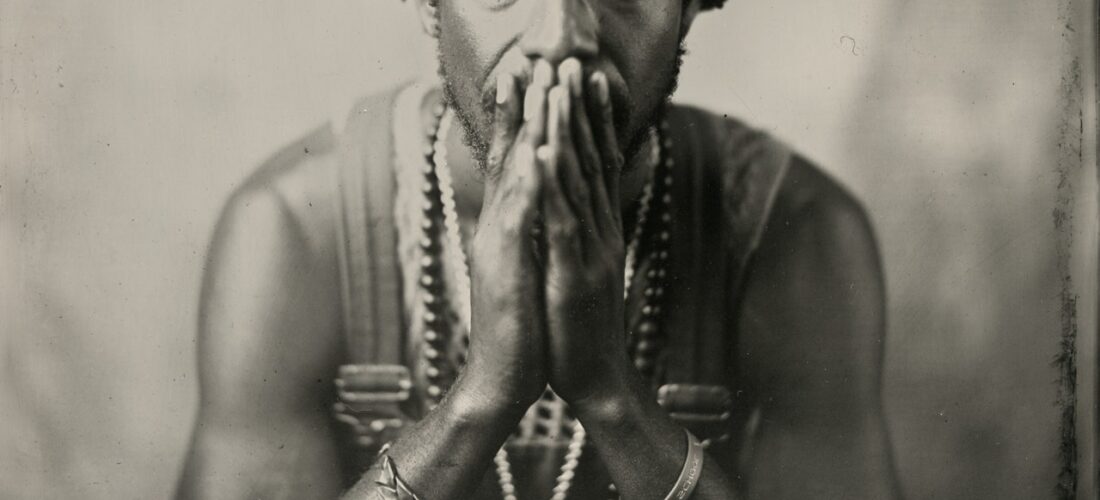

It’s easy to admire Shabaka’s stated reasons for putting down the horn: a feeling of burnout stemming from a heavy touring schedule that has kept him “on the road consistently treating the performance of a spiritual practice as a commodity to be sold repeatedly”; a quest to generate “energy without tension,” which has led him instead toward various flutes, including the Japanese shakuhachi and the clarinet, his original and, in his eyes, principle instrument. But could a Shabaka album with almost no tenor really have the same impact as his prior output? The answer is yes, absolutely, and that’s primarily because on Perceive Its Beauty, Acknowledge Its Grace—the artist’s first full-length statement in this vein, following a 2022 EP, Afrikan Culture—Shabaka hasn’t just subbed out one signature instrument for another; instead, he’s remade his music from the ground up.

Shabaka’s prior work was as much dance music as jazz. You couldn’t help but move to the heady electro-funk of the Comet Is Coming, the mighty Afro-Caribbean grooves of Sons of Kemet, or the richly layered intercontinental exchange of Shabaka and the Ancestors. Perceive Its Beauty, on the other hand, focuses on tranquility, a sense of meditative communion with a variety of guest vocalists and instrumentalists. Of course, Shabaka is hardly the only musician thinking along these lines lately. New Blue Sun, André 3000’s own flute-pivot LP, which featured a Shabaka cameo on shakuhachi, signaled the mainstream arrival of a wave that’s been building steadily across the past decade or so wherein various questing sounds of the 1970s—from Alice Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders to Steve Reich, Brian Eno and private-press New Agers like Iasos— have swirled together in a plume of incense, wafting across the decades to inform artists working in and around jazz, electronic music, and more.