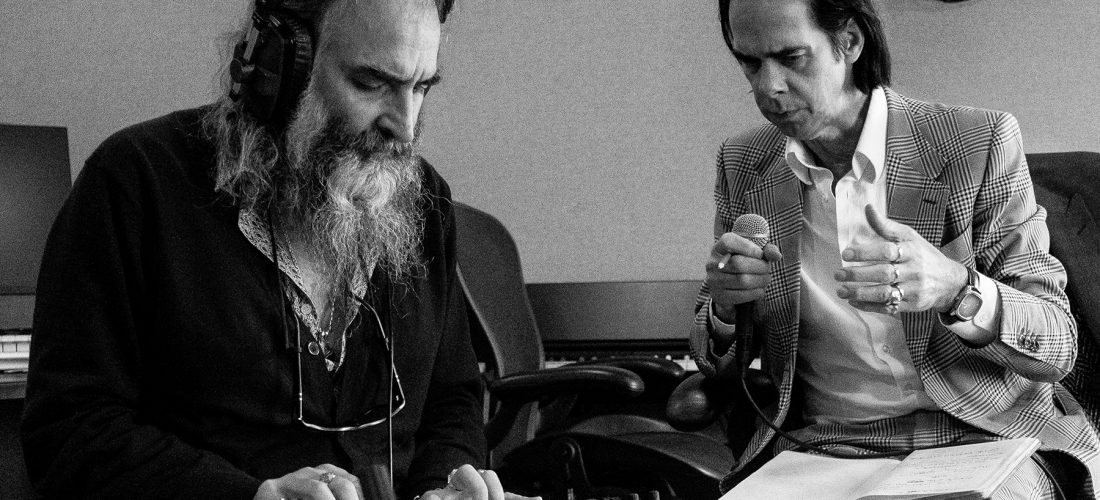

Nick Cave and Warren Ellis Find Hope Amid Today’s Sorrows on ‘Carnage’

Carnage would be a broad subject for any artist, especially anyone who has devoted an album solely to the art of the murder ballad. But this is Nick Cave, and in true Bad Seed fashion, there’s a twist: The crime scene here is spiritual rather than corporeal.

Carnage, a collaboration between Cave and Bad Seeds multi-instrumentalist Warren Ellis, is a relatively quiet meditation on spiritual salvation in the era of loneliness. On each of the record’s eight tracks, Cave attempts to make sense of his place in the world, as he sees it crumbling around him. When he thinks of love on the title track, it’s “with a little bit of rain, and I hope to see you again.” Deeper into the album, on “Shattered Ground,” his love is diffuse, “Everywhere you are, I am,” he sings into an ether of synthesized strings, “and everywhere you are, I will hold your hand again.”

If any artist were prepared for months of lockdown and social distancing, it would be Cave, whose music has dealt explicitly with loss for decades. Whether on the abject outbursts of his alma mater, art-punks the Birthday Party, or on the plaintive mourning and exalted ghost stories of the first nine Bad Seeds long players, he’s always reveled in the macabre. In the years following the death of his son, Arthur, grief was no longer his muse, but rather something he desperately wanted to escape. His most recent album, the exquisite 2019 LP, Ghosteen, was a gorgeous and heartbreaking two-part suite written from the perspectives of both children who have died and the parents mourning them. But as he navigated that album’s sad waters, Cave started turning his ship around in search of hope.

Carnage, in some strange way, is a glimmer of optimism. Many of its songs are about the time-worn subject of bidding farewell to someone you love (Cave even name-checks “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” on “Old Time”), but in a surprise twist, those same tunes are also about reunions. “Albuquerque,” oddly, is about feeling happy staying put: “And we won’t get to anywhere, anytime this year, darling,” Cave sings over a weepy synth bed, adding, “unless I dream you there … unless you take me there.” On “Lavender Fields,” with its slowly undulating orchestral strings, he narrates, “I am travelling appallingly alone on a singular road,” even though he knows that with his dedicated fanbase, that has never been the case. “We don’t ask who, we don’t ask why,” a choir responds to him him later in the song, “There is a kingdom in the sky.”

Since at least the second Bad Seeds record, 1985’s The Firstborn Is Dead, Cave has been alluding to kings and kingdoms. Then, the kingdom was Tupelo, Mississippi, birthplace of the inspiration for Cave’s trademark coiffure (and the King of Rock & Roll), Elvis Presley. By the Nineties, on The Boatman’s Call — the record, where Cave finally left guile behind in his search of true love and devotion — the kingdom is finally biblical, a place he hopes to dwell one day with his lover. It’s about as gothic as Christian rock gets. That kingdom is the same as the one on Carnage, though it feels more distant here.

On the album opener, “Hand of God,” a sparse yet noisy, deconstructionist blues, he sings of people in search of Heaven, but shifts it into a story of survival, hoping for intervention (this from the same singer who opened The Boatman’s Call with “I don’t believe in an interventionist God”). It’s stark and evocative, especially as a voice sings, “hand of god,” in falsetto behind his baritone. Ellis’ strings swell around him, like waves overtaking him. And on the baroque-sounding “Lavender Fields,” Cave is ploughing through “this furious world, of which I’m truly over,” in search of deliverance.

The Kingdom takes on a more sinister guise on “White Elephant,” a thinly veiled jab at right-wing extremists (remember, the elephant is a political effigy). Here, God represents Old Testament vengeance. God is a protester “kneeling on the neck of a statue … that says, ‘I can’t breathe’/The protester says, ‘Now you know how it feels.’” Here, God is “a Botticelli Venus with a penis” with an “elephant gun of tears.” But halfway through the song, with the sound of machine-gun drumming, the violence ends abruptly, and Cave and a choir sing rapturously, “A time is coming, a time is nigh/For the Kingdom in the Sky.” It’s a moment when the clouds park and hope shines in.

Outside of the Bad Seeds, Cave and Ellis have spent the past 16 years working on film scores, and they have developed a mutual understanding that allows the music to work in concert with Cave’s words. When the lyrics are despairing, the backdrop is somber and droning; when they’re hopeful, as on the end of “White Elephant,” it’s beatific. And even though there aren’t a dozen Bad Seeds supporting Cave this time (though drummer Thomas Wydler pops up on “Old Time”), Ellis plays 11 instruments including harmonium, autoharp, and glockenspiel, while Cave handles piano, synthesizer, and percussion. For as sparse as it sounds, there’s great depth to Carnage.

Ultimately, Cave’s message seems to be that only through togetherness and unity in spirit can people rise above the carnage — the depression, the fear, the prejudice, the ugliness — of this grim moment. “There’s a madness in her and a madness in me,” he sings on “Shattered Ground,” “And together it forms a kind of sanity.” And he closes the record, singing with a choir, “This morning is amazing and so are you,” over and over, before telling his lover, “You are languid and lovely and lazy/And what doesn’t kill you just makes you crazier.” It’s Cave’s way of saying he will stick this thing out until the end, no matter what tempest lies ahead.