This may be the greatest radio station you’ve ever come across. Unless it’s multiple stations talking over each other, in and out of range. Sounds arrive in strange combinations; nothing is quite exactly the way you remember. Did that classic rock band really have a synth player, and why did they pick a patch that sounds like a mosquito buzzing through a cheap distortion pedal? And those eerie harmonies swirling at the outskirts of that last-dance ballad by some 1960s girl group whose name ends in -elles or -ettes. Did they hire a few heartbroken ghosts who were hanging around the studio as backing vocalists? Or are these fragments of other songs, other signals, surfacing like distant headlights over a hill, then disappearing once more?

Or maybe this is Diamond Jubilee, the sprawling and spectacular new album by Cindy Lee: two hours, 32 songs, each one like a foggy transmission from a rock’n’roll netherworld with its own ghostly canon of beloved hits. Like much of Lee’s past work, its spiritual center is girl group music, reduced to a single girl and reflected through a hall of mirrors. From there, it extends toward the far reaches of the radio dial, and sometimes beyond: the warped classic rock of “Glitz,” the fragmented disco of “Olive Drab,” the sunburnt psychedelia of the title track, the nocturnal synth-pop of “GAYBLEVISION.” “Darling of the Diskoteque” sounds like Tom Waits and Marc Ribot masquerading as Santo and Johnny; “Le Machiniste Fantome” like a cue from some fictional Ennio Morricone score to a film about 9th-century monks. But even at its most idiosyncratic, the music conveys the archetypal yearning of pop. Nearly every song is about a lover who’s gone, and the dream that their loss—the solitary moonlit nights, the resolve to move on, the resignation to wallow forever—might be as romantic as the love itself.

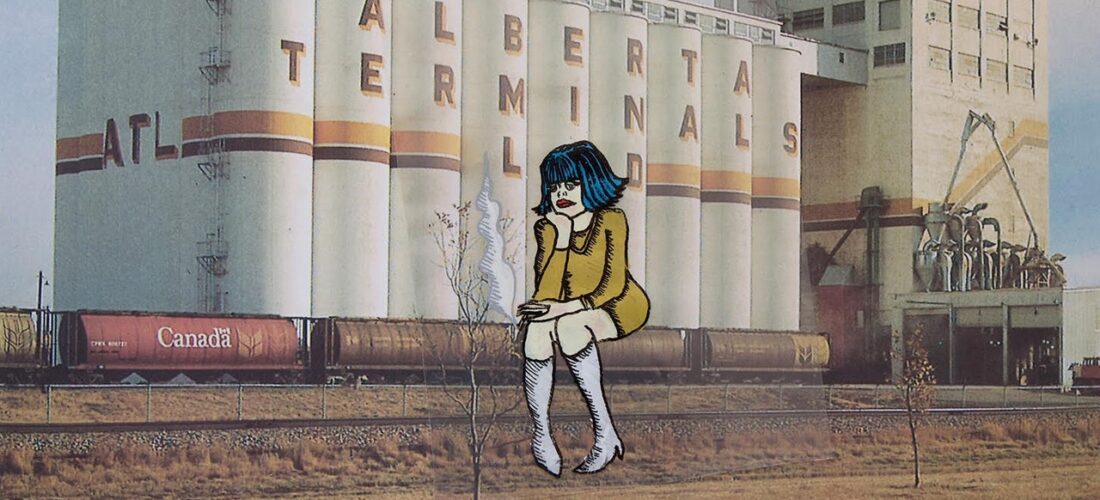

Lee is the glammed-up alter ego of songwriter, guitarist, and drag performer Patrick Flegel. In a different lifetime, they were the frontperson of Women, a brilliant and volatile Canadian post-punk band of the late 2000s. They flamed out quickly after two albums, an onstage fistfight, and the unrelated sudden death of one member, but their spindly guitar lines, asymmetrical rhythms, and surprisingly sweet melodies have remained influential on wide swaths of DIY rock. Flegel’s old bandmates formed Preoccupations and soon gravitated toward the crisp sonics and propulsive grooves of new wave. If Preoccupations found a stable middle ground between their old band’s extremes, Flegel pushed further out in both directions, donning a blue bob wig and Nancy Sinatra boots and releasing a series of albums as Cindy Lee that set pure pop songwriting alongside confrontational blasts of feedback.