Hayden Anhedönia wanted to make films. But like so many girls from small-town America, her ambitions outpaced her means. Instead, she wrote music: atmospheric, genre-blurring, and (crucially) low-budget songs that could soundtrack a séance. Ethel Cain, a character in her imagined cinematic universe, became her musical alter ego and the protagonist of Preacher’s Daughter, her 2022 debut. Anhedönia didn’t need Hollywood backing to style herself as an auteur: She wrote, performed, and produced her songs largely alone, while cultivating a camera-ready tradwife-meets-trucker aesthetic. Unguarded about the scope of her dreams, she echoed one of her most obvious forebearers when, in 2021, she said that she wanted hers to be the “next great American record.”

Preacher’s Daughter was billed as the first installment of a trilogy following three generations of women—Ethel Cain being the youngest—in a Southern evangelical setting with evident parallels to Anhedönia’s own upbringing in the Florida panhandle. The story, a grisly travelogue, is pocked by familial trauma, perverse sex, even cannibalism. Its somewhat tamer new prequel, Willoughby Tucker, I’ll Always Love You, has a younger Cain ensnared in a teenage love triangle with the title character and death. Sprawling as it is, the project, so far, coheres around its defining theme of fragility—of life, of love, and of the American dream.

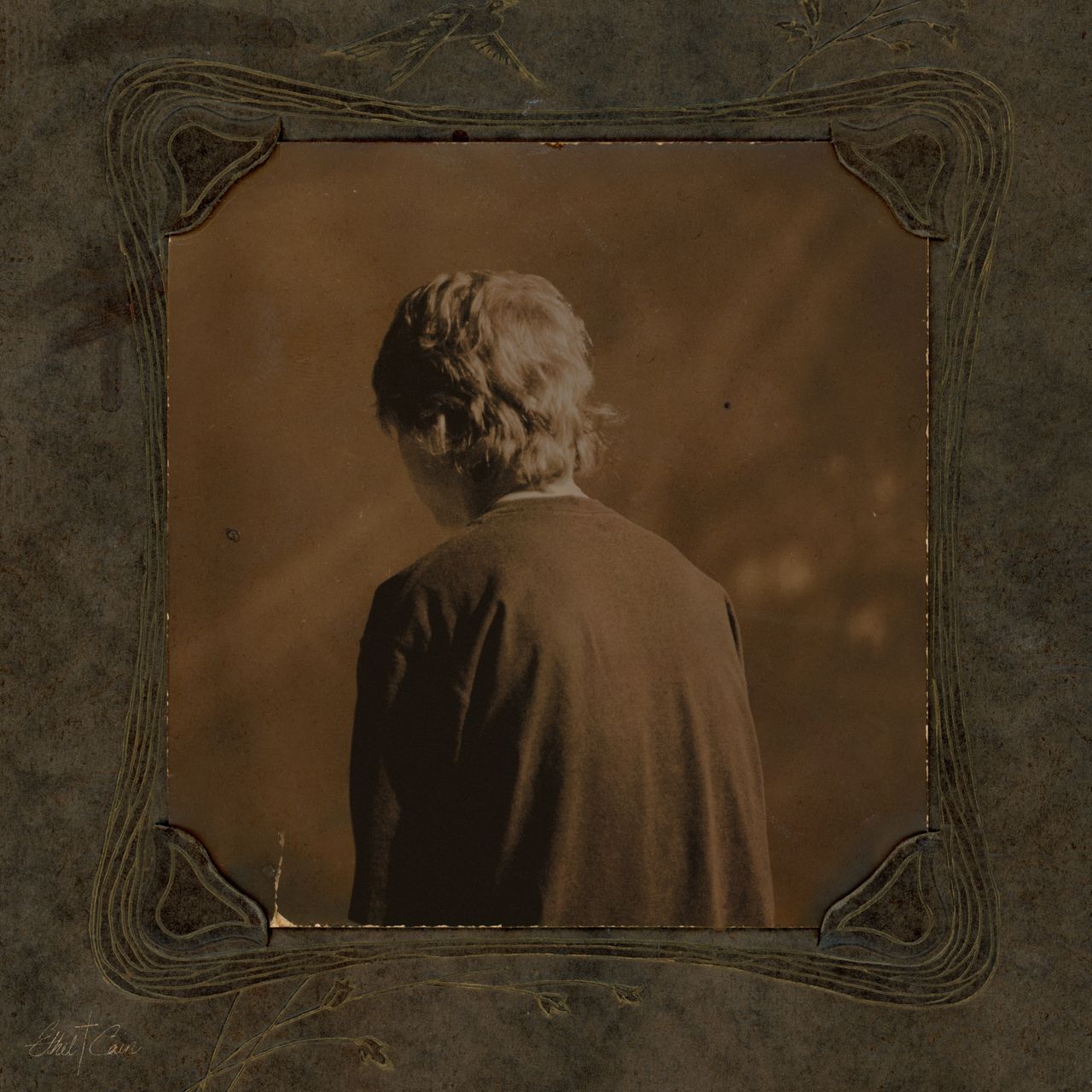

You’d be forgiven for not getting all of that just from listening. While loaded with backstory, these records subsist more on ambiance than on plot. Anhedönia, often classified as a pop artist, gravitates equally—and on Willoughby Tucker, increasingly—to sludgy slowcore and dusty, sepia-toned folk; to sounds that are laggy and distorted, like dinged-up records played at the wrong speed. (For a more extreme application of this interest, see Perverts, the ambient album she released in January.) Her characters are illuminated in lightning bolts of imagery rather than in continuous tracking shots: The love interest on “Dust Bowl” is a beautiful and tortured “natural blood-stained blond” who takes her to see slasher flicks at the drive-in; elsewhere, Cain languishes in a stale, mildewy bedroom and in pallid hospital light. In the darkness between these flashes, Anhedönia smears drones and lap steel and tape crackle and cardiac monitor beeps into murky abstraction.

And then there’s “Fuck Me Eyes,” Willoughby Tucker’s second single. A tender, colorful character study of a teenaged town harlot, the song features some of Anhedönia’s sharpest writing (“Three years undefeated as Miss Holiday Inn”) and most maximal production—all twinkly ’80 synths and booming percussion—as it probes the gap between desire and acceptance. Sonically, it’s a headfake, a play she’s run before: “American Teenager,” the arena-ready single from Preacher’s Daughter, is similarly at odds with its context. On its own, “Fuck Me Eyes” is captivating. In situ, it has the feeling of a box ticked—the legible pop song that exists to justify the unmarketable creative choices surrounding it.