Why Are Donald Trump and Tim Walz Both Talking About Bruce Springsteen?

Just over 40 years ago, Ronald Reagan became the first American president to name-drop Bruce Springsteen. “America’s future rests in a thousand dreams inside your hearts,” he told a crowd at a New Jersey campaign stop in September of 1984. “It rests in the message of hope in the songs of a man so many young Americans admire — New Jersey’s own, Bruce Springsteen.”

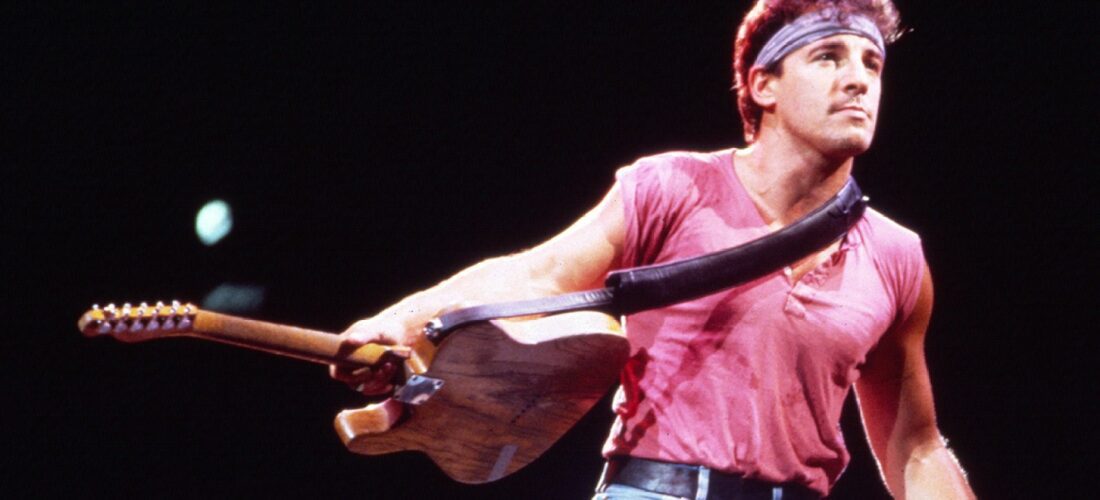

Springsteen was, of course, at a pop-cultural peak in that moment, fresh from the release of the world-conquering blockbuster Born in the U.S.A., with a flag on the cover and an easy-to-misconstrue title track. In the decades since, he’s made his left-leaning political views quite clear, campaigning for Democratic candidates and even partnering with Barack Obama for a podcast series and book. And even in the far-flung political era of 2024, where Beyoncé’s “Freedom” scores Kamala Harris‘ campaign, Springsteen’s name and music keep popping up — Donald Trump has him on his mind, Tim Walz is a vocal fan, and “Born in the U.S.A.” played at the Democratic National Convention.

Steven Hyden‘s excellent new book, There Was Nothing You Could Do: Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the U.S.A. and the End of the Heartland, traces the pop-cultural and political impact of that album. He recently sat down with Rolling Stone to discuss Springsteen’s continuing political relevance and more. (To hear more from Hyden on his book, check out the Rolling Stone Music Now podcast — his segment begins around the 42-minute mark of the Katy Perry episode above. Go here for the podcast provider of your choice, listen on Apple Podcasts or Spotify, or just press play above.)

The first big Springsteen moment of this campaign was when Donald Trump started musing onstage, pretty much out of nowhere, about the fact that Bruce doesn’t like him. What did you make of that, especially in the context of your book?

Trump’s relationship with classic rock is really interesting. He’s obviously a big fan of Sixties and Seventies rock music, as a lot of people his age are, and it’s an awkward situation because it’s not reciprocated from any of these people — Springsteen among them. These are his heroes, in some respects, at least musically speaking, and yet they view him unanimously as being bad for the country.

There’s so many musicians who don’t like Trump, but he keeps zeroing in on Springsteen. The fact that Bruce doesn’t like him — called him a moron, specifically, when I talked to him for Rolling Stone in 2016 — really bothers him. And I think that’s connected to the way Bruce carries some sort of American weight that other rock stars don’t.

Yeah, I think there is something with Bruce where that felt true 40 years ago, and it’s probably even more true now. He’s not seen totally as a political figure, but he feels more like a political figure than any other rock star. But he also has the populist thing going with him. There’s probably a part of Trump that feels like these are the people that I’m speaking to — Bruce should respond to me as well because he’s the middle-American-type guy, speaking up for average Americans. Now, of course, Trump isn’t actually doing that, but I think that there is some delusional thing in his mind, thinking that he and Springsteen in some ways are on the same side. So there probably is a little extra sting there, to not get that acceptance from Bruce.

As you mentioned in your book, in 2016 The New York Times tracked down an actual mill worker Bruce wrote about in the song “Youngstown,” and that guy said he was voting for Trump. There is that sense that Springsteen and Trump have been trying to speak to and for some of the same people in some ways.

It says something about how the politics of rural middle America have shifted over time. In the Eighties, it was much easier to find a blue-collar worker who worked in a factory who was also a Democrat. There was that sort of hard-hat Democrat who existed 40 years ago that you don’t see as much now, and it feels like a lot of that just has to do with culture-war type stuff, things like how people on the left and right present themselves to people in the middle of the country. So yeah, if you’re looking for a metaphor for how America has changed, the idea of characters in Bruce Springsteen songs who become Trump voters, obviously that was something that attracted me. That’s such a convenient metaphor for how the country has changed in the last 40 years.

And then Tim Walz came along. He’s a big music guy in general, but he’s definitely a huge Springsteen fan — there’s this video where he discusses his musical tastes with Harris and the first thing he mentions is The River.

Yeah, I think with Walz, his music taste has been one of the ways in which he’s presented himself as a normal guy, which becomes a big part of this campaign stigmatizing Republicans as the weird ones. But I think when he talks about Bruce Springsteen, people read that as, “Oh, he reminds me of my dad, or he reminds me of my uncle,” and it humanizes him in a very quick shorthand kind of way. I think that also just speaks to Springsteen’s place in the culture. When Obama was elected, Bruce was in his late fifties, so there was still something about Bruce that was a little younger, maybe. But now we’re at a point where when you think about Springsteen, it is something that your dad or maybe even your granddad likes. But it’s a positive thing. He is part of that all-American package, but also progressive at the same time. It’s like what we were saying before, it is almost like a throwback to that idea that you can be blue collar, but you can also believe in trans rights and defend abortion rights, and those things don’t have to be incompatible.

I think it’s fair to say that while Bruce is definitely associated with an older fanbase, there are also a good number of younger serious music fans and certainly younger artists who love him. He’s been cool on an indie level for maybe 20 years now, since Arcade Fire and the Killers first embraced him.

I feel like he took up the mantle that Johnny Cash used to have. He was like the older guy that younger generations always discover as, like, a beacon of integrity.

Or like Neil Young in the Nineties.

And Neil still to a degree, but with Johnny Cash and Springsteen, there’s also something very American about both of them. They are very masculine tough guys, yet there’s also a sensitivity to them. They are progressive politically. It balances a lot of the things that people value in America — that individualism, that toughness, but also a thoughtfulness. It’s like the positive side of people chanting “U.S.A.” in a crowd. Not the jingoistic, stupid, reactionary aspects, but the righteous side. For people of my generation, Johnny Cash was that person. And then Johnny Cash passes away.

And that’s around the time that Springsteen, I think, takes up that mantle, around the mid-2000s, and he’s had it since then. it’s interesting to see Bruce pop up in other people’s songs, where I feel like he’s a symbol of that. Zach Bryan being the most recent example. I love that the song is called “Sandpaper,” by the way, because Bruce is super-raspy, even raspier than usual. in that song. He feels very totemistic to me, like putting a bald eagle into your song, or something like that. And the Killers re-recorded “A Dustland Fairytale” and Bruce sang on it. That kind of reminds me of when U2 had Johnny Cash show up on a song. There’s a power to him as a symbol — he might as well be a bald eagle or an American flag or an apple pie or any other symbol of America you could think of.

Which again is why it bothers Trump so much that he doesn’t like him. As we’ve discussed, if there wasn’t that 1984 to 1985 period, where he used the title “Born in the U.S.A.,” shot an album cover with the flag on it, and had a flag onstage, this might all be seen slightly differently.

Yeah, exactly. That definitely put a fine point on it. Clearly he was already writing about working-class Americans before that, but the symbolism of “Born in the U.S.A.” and the success of it, the fact that it was so ubiquitous, is still so burned into people’s consciousness. In my first book, I wrote about Chris Christie and Bruce Springsteen and how weird it must be for Chris Christie to be this huge Bruce Springsteen fan and to know that Bruce, at least politically, does not like him at all. And I think that does speak to how, and this might be true of Trump as well, even though we know where Bruce stands politically, it’s still possible to take different things out of his songs, depending on where you fall. There’s a lot of things in his music that if you are conservative, you can relate to. And it just requires the mental jujitsu to block out the other stuff, which people do with songs all the time. We always disregard things that don’t align with our own experiences. We’ll latch on to one lyric or something and make the whole song about that. Because clearly there’s a lot of Republicans who love Bruce Springsteen. I think that’s been true forever. If you are conservative, there are things you can take from him that align with how you see America. it just forces you to disregard a lot of other things that are inconvenient.

I also think that was easier to say, frankly, pre-MAGA. I feel like it’s hard to be like, I’m a MAGA Republican and these are the five things I hear in Bruce’s music that will support my MAGA-ness.

I do think that there’s a lot of people who vote for Trump who are not like the people that we see talking online. I know people like this in my life who vote for Trump. Because they just always vote for Republicans. I mean, when Springsteen plays Jersey, I don’t think all the people in that stadium are Democrats. I think it’s probably more even than it would seem, but, we don’t know that for sure. We’d have to do a poll.

That’s fair. Finally, we heard “Born in the U.S.A.” at least twice during the DNC. This was a case of Democrats using, or misusing the song, the way Republicans more traditionally do — as a rousing, patriotic anthem. But is the pained, betrayed, angry patriotism of “Born in the U.S.A.” actually okay in this DNC context, given that we know this is the party its creator supports, or is it still weird?

It’s a little weird! But that song in an arena environment always takes on a whole other character that transcends the lyrics. The music is so rousing; the chorus compels you to sing along. And if you get into that group-mind situation, it’s very easy to ignore the nuances in the lyrics. If you’re in a crowd of 20,000 people and you try to say, “This is actually a critique of America, not a celebration,” you’re going to get drowned out by people shouting “Born in the U.S.A.” It’s just how that goes. And it’s part of the power and the problematic nature of that song

It’s funny that the New Jersey delegation used it as their theme song. The song is clearly set in New Jersey, based on the gas fires and the refinery and whatnot. And so the “dead man’s town” in the first line is a town in New Jersey.

It would be even funnier if it was “Born to Run” because that song arguably paints an even bleaker picture of New Jersey. He’s not really writing about it being this sort of paradise where everything works out great. That’s not the Jersey of Bruce Springsteen songs.