In theory, the MTV Video Music Awards are an annual celebration of the year’s best music videos. In practice, the VMAs celebrate celebrities, and in 1992, that made for quite a guest list. Eric Clapton! Marky Mark! Garth Algar! The party brought together a coalition of aging rockers, buzzy new artists and Bobby Brown, all performing between a series of “zany” juxtapositions—think David Spade refusing backstage entry to Hellraiser’s Pinhead—but the ceremony’s most notable pairing would go down off-camera.

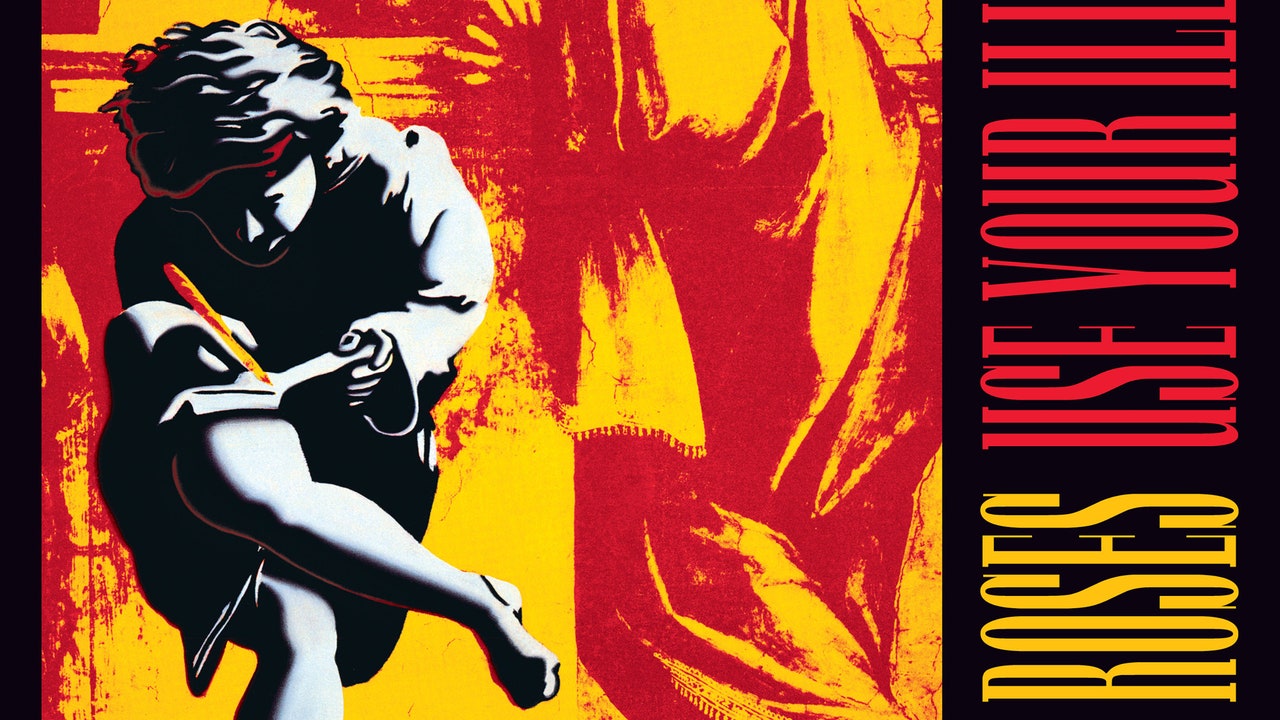

At that moment, Guns N’ Roses were the biggest band in the world, outlaw rockers flying high off Use Your Illusion I and Use Your Illusion II, a pair of megahit albums released on the same day the previous fall. They were in attendance so surviving members of Queen could present them with the Video Vanguard award for their visual oeuvre, including “November Rain,” the crown jewel in a series of morbid fantasies frontman W. Axl Rose commissioned to promote Illusion I and II.

GnR’s labelmates, Nirvana, were also there, thanks to their own hit album, Nevermind, released a week after Illusion; despite sharing distortion pedals and David Geffen’s largesse, Nevermind heralded singer and songwriter Kurt Cobain’s radically different approach to being a guitar group. Ever on brand, GnR tried to goad them into a backstage fistfight, but Kurt met Axl’s threats with signature sarcasm. Guns N’ Roses closed the night with a triumphant, Elton John-assisted performance of “November Rain,” but Nirvana—whose own shambolic set ended with drummer Dave Grohl yelling “Where’s Axl?” into the mic—left the show victorious.

It’s easy to read this moment as a changing of the guard—and make no mistake, it was—but over time, the truth becomes a bit more slippery. The two volumes of Illusion were the sequel to 1987’s Appetite For Destruction, which, like Nevermind, was a vibe-shifting perfect record, one that would inject actual menace into an increasingly commercialized Reagan-era rock scene and blast Axl, guitarists Slash and Izzy Stradlin, bassist Duff McKagan and drummer Steven Adler from Hollywood gutters to the outer reaches of the global music stratosphere in the process.