In the waning weeks of 1970, Alice Coltrane put the finishing touches on her latest album, Journey in Satchidananda, recorded in the basement of her Long Island home, in a studio her late husband John Coltrane had conceived, but didn’t live to see through to completion. She wrote the album’s liner notes and commented on her imminent five-week trip through India and Ceylon (soon to be rechristened Sri Lanka) with her guru, Swami Satchidananda. But for the seekers and yoga students who idealize the spiritual airs of India, the street-level air of the country can be a rude awakening. There’s a reason that both meditation and incense originate there, as the sensory overload is profound and pungent. Mindful breathing might include snootfuls of diesel exhaust and frangipani, curry and cow dung, rot and sandalwood. Coltrane’s grand-nephew, Flying Lotus, would later describe that scent to me as “the funk of ages” recalling travelling with her there decades later.

And then there was Alice, a tall Black woman from America, amid the bustle of the country, lugging a magnificent harp everywhere. “It was stunning to people there that somebody came from the West to play. She made quite an impression—but she was always very modest,” one student said. A 16 mm film documenting the travels of Satchidananda at that time also offers up the sight of Alice Coltrane—who grew up in the Baptist church in Detroit’s Paradise Valley neighborhood—being plunged in the frigid, clear sacred waters of the Ganges River way up in the Himalayas. She would welcome the new year in India. After five weeks there, Coltrane returned to the United States revitalized and reborn.

As she would explain in an interview with Columbia University student radio station WKCR later in 1971: “The past four years have really been involved in that aspect of really trying to see what’s going on and finding my place in the spiritual world. So now I feel that I’ve gotten some answers; I’ve gotten quite a few answers. There isn’t such an urgency as it was before to really go into meditation and spend so many hours in-drawn. Now I feel that I’ve been given an opportunity to come out, to be with you tonight, to play, and get into music. This is really what I felt from the meditation. Now is the time to really look at music.”

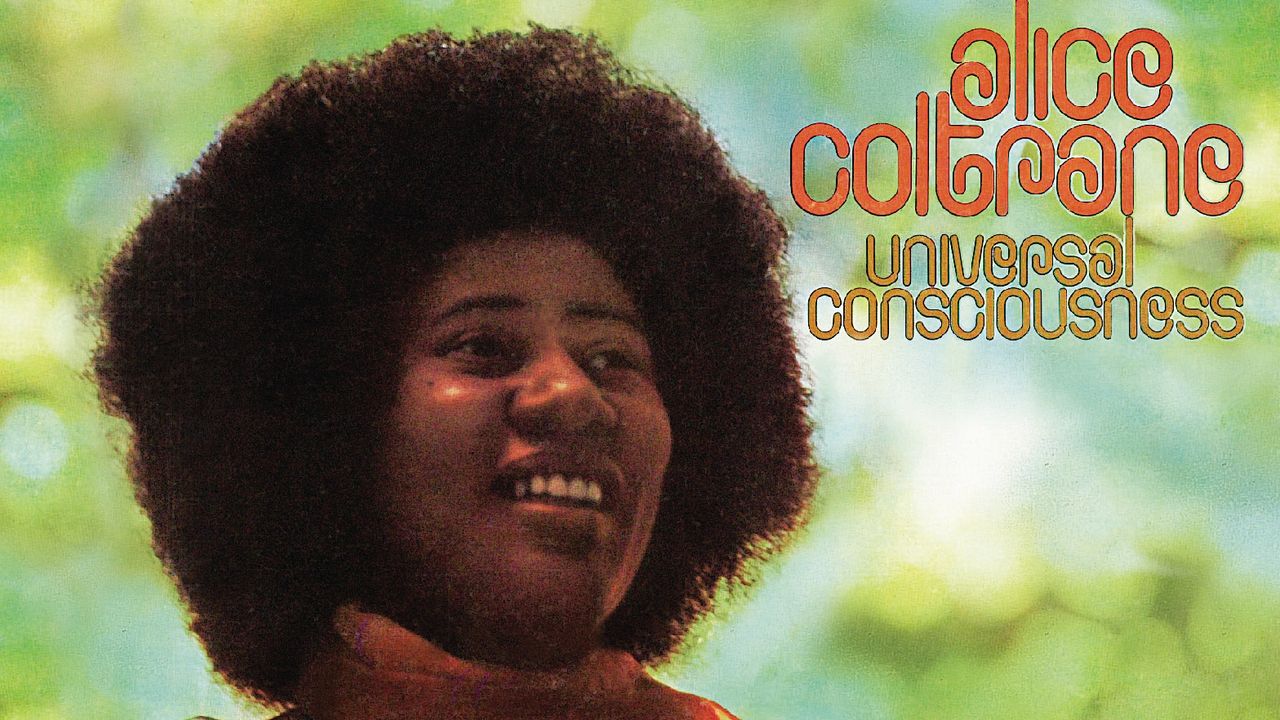

That urgency, those answered answers, that sense of her place in the spiritual world, that deep look at music, all are conveyed in Coltrane’s fifth studio album, Universal Consciousness. Composed barely five months after the spiritual jazz masterpiece Journey in Satchidananda, Universal Consciousness is every bit the equal of its predecessor and at times soars even further into stratospheric realms.