Haruomi Hosono was obsessed with American music. Growing up in postwar Japan, he ignored domestic artists and listened to foreign sounds broadcast by the Far East Network, radio stations operated by the U.S. military. One of his childhood favorites can be considered the most consequential track of his early solo career: Martin Denny’s “Quiet Village.” The song, which nabbed the fourth spot on Billboard’s Hot 100 in 1959, brought exotica to the masses, ushering in new possibilities for sonic fantasy. “My music has always been fiction,” Denny said in 1998. “Everything comes from my imagination… it wasn’t about authenticity.” In the mid-’70s, Hosono was listening to Caribbean music but didn’t think he had the chops to make the real stuff. Exotica provided a way in—the freedom to be an amateur.

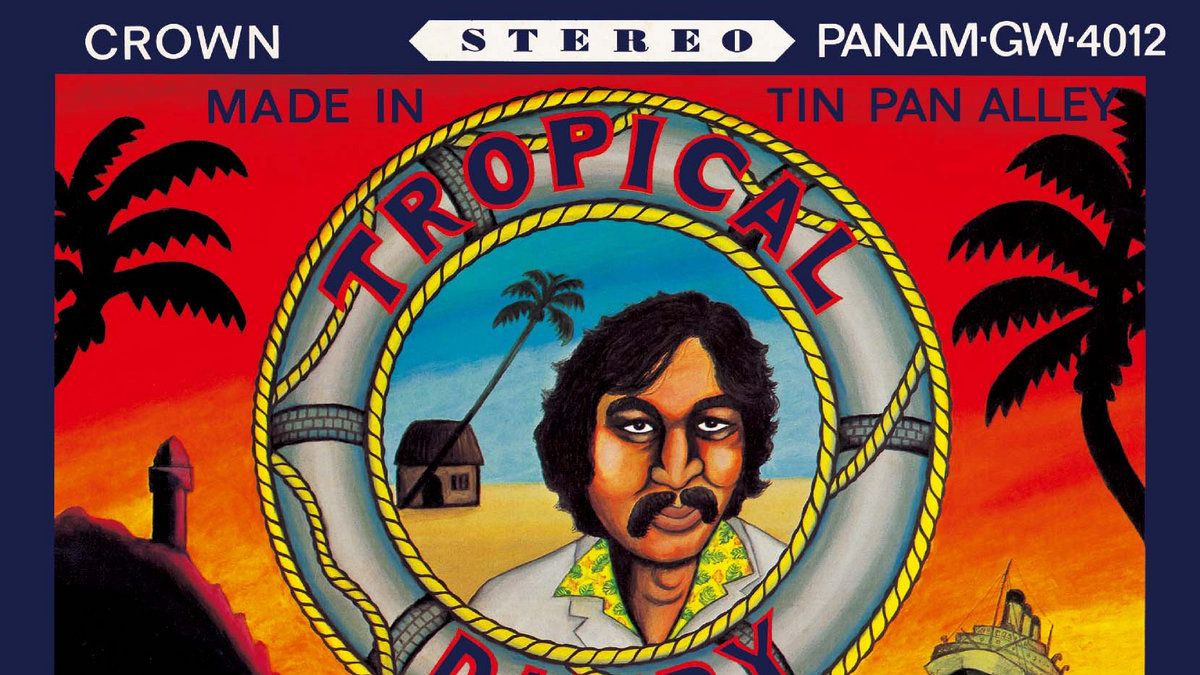

“Quiet Village” was an important reference point for Hosono’s second solo LP, Tropical Dandy, the 1975 album that inaugurated his “Tropical Trilogy.” What he liked about the song was what the rest of its global audience liked too: the vision of an entirely idealized place. Compared to Les Baxter’s original orchestral arrangement, Denny’s rendition was modest, featuring imitations of animals to conjure a picturesque landscape (the song was first performed amid croaking frogs, inspiring the creative decision). This scene-setting is the final touch Hosono added to “Nettaiya,” a remarkable soft-rock daydream that uses lapping waves as musical interludes. Over hushed ukulele he sings about Tokyo and Shanghai, Trinidad and Minnesota, the diverse locales serving as touchstones for an idyllic, eternal beachside—that is, until he complains that paradise is insufferably hot. Hosono’s take on exotica is both reflexive and funny, confronting listeners with its illusory nature.

“Let’s embark on this journey together before the Japanese archipelago sinks into the ocean,” Hosono writes at the end of Tropical Dandy’s liner notes. His mission, as he saw it, was to take music that traversed numerous countries and then add his own flavor. He dubbed this worldly style “Soy Sauce Music,” seeing his work as an extension of what all great songs did: engage in a rich and never-ending global conversation. The album’s opener makes good on that promise. He covers Glenn Miller’s big-band hit “Chattanooga Choo Choo” but sings it in Portuguese, riffing on Carmen Miranda’s version from 1942. You can hear the homage in the way his band lifts the scat interludes, but they also begin with a Sly and the Family Stone-like funk groove, throw in swing piano detours, and make space for guitar and trumpet solos. Even more, it’s suffused with the boisterous spirit of calypso music, especially because Hosono’s nasally delivery recalls the genre’s most humorous raconteur, Mighty Sparrow.