In 1956, Robert Zimmerman was a 15-year-old kid, a misfit in his small Midwestern town, and leader of a ragtag rock’n’roll combo who compensated for their lack of technique with boundless enthusiasm. In 1963, Bob Dylan was arguably the most celebrated pop artist in America, whose songs were hailed as standards before he could even record them and whose fans considered him to be a living, breathing manifestation of the American folk impulse. That kid wailing on his band’s cover of Shirley & Lee’s “Let the Good Times Roll” back in St. Paul, Minnesota, could never have predicted where he’d end up in seven years (he’d not even heard of Odetta or Woody Guthrie yet), and the conquering hero closing out his first sold-out Carnegie Hall performance with a spirited and weirdly prophetic “When the Ship Comes In” had already tried to erase his old self from his biography. He claimed to friends and interviewers and colleagues and onlookers that he was born and raised in New Mexico, ran off with the circus, toured with Conway Twitty, and any other fabulation that crossed his mind, so perhaps he thought those two versions of himself were incompatible. But there was always something of the rocker in the folkie and a bit of the folkie in the rocker.

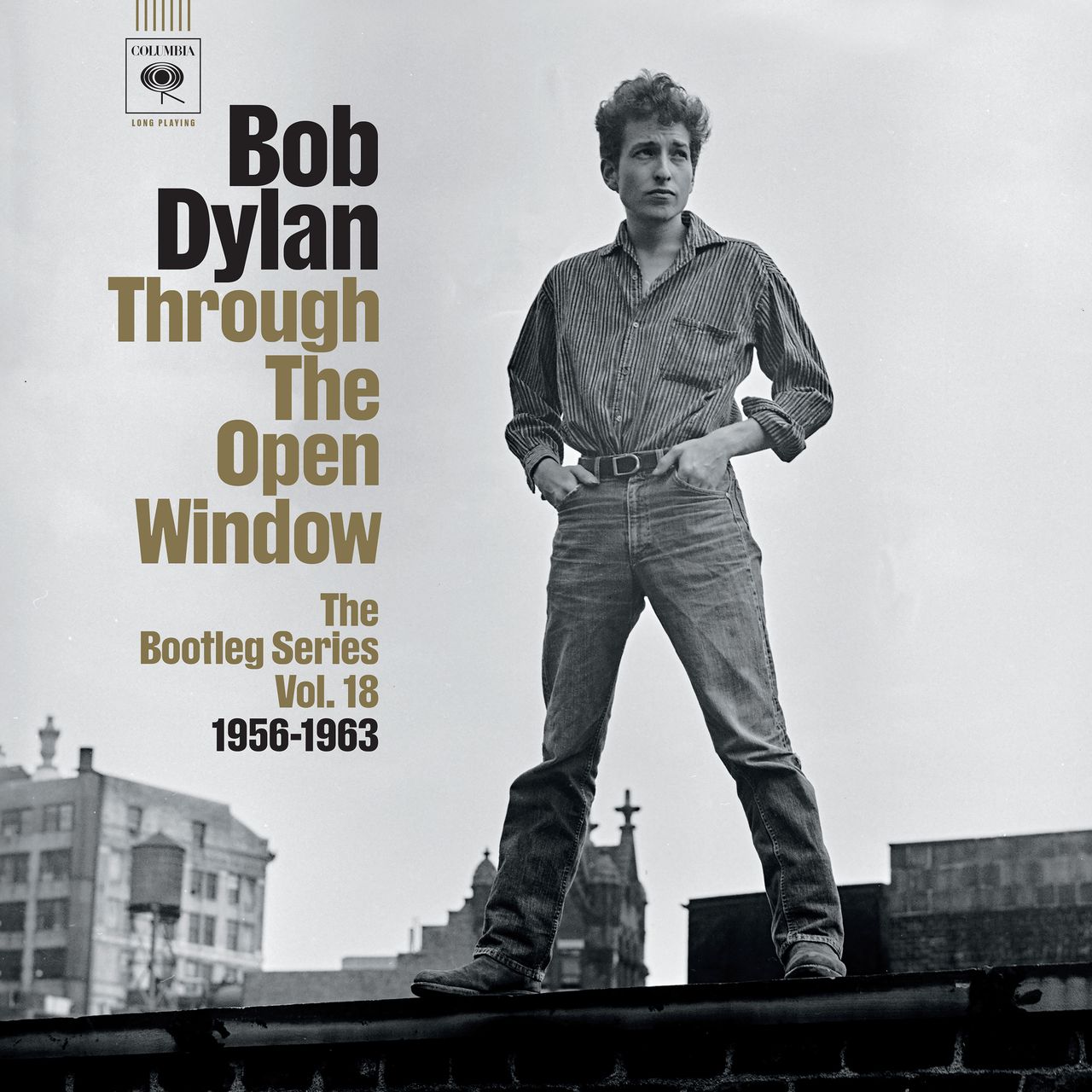

Through the Open Window, the 18th installment of Dylan’s never-ending reissue series, connects these two figures intimately, tracing the artist’s seven-year rise across 8 CDs, 165 tracks, and nearly nine hours. It’s not the largest Bootleg entry; the collector’s edition of The Cutting Edge beats all comers with 18 CDs, while Trouble No More sprawls to as many as 10 CDs. (You want that much mid-’60s electric Dylan, but who besides the most committed Bobophile needs that much born-again Dylan?) Regardless, nothing in the series has the same scope of this new set. Most Bootleg installments drop you into a pivotal moment in Dylan’s life, a meaningful year or two, but Through the Open Window covers almost a decade during which he made great strides. It plays less like a box set and more like the audiobook of a Great American Novel: a travelogue from the Midwest to Greenwich Village and a coming-of-age story of an artist hitting young adulthood amid the dreamers and schemers of New York City. It follows Dylan as he hangs out in shabby Manhattan apartments, as he lingers over coffee at Café Wha?, and as he tries out new songs and routines and personae onstage. It follows him into tiny Cue Recording Studio and historic Columbia Studio A, to a poorly attended show at the tiny Carnegie Chapter Hall, and finally to his climactic sold-out show at Carnegie Hall.