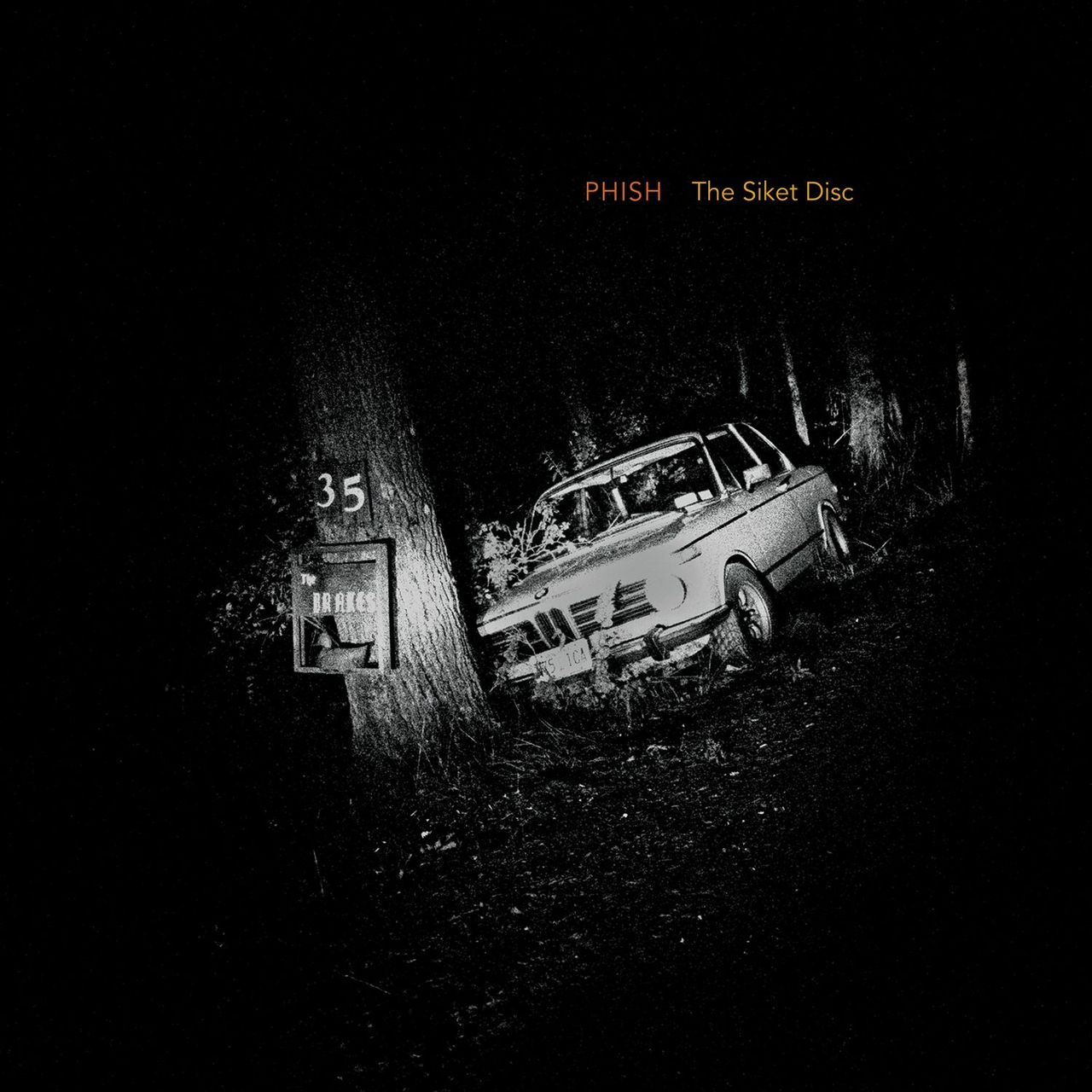

In 1997, Phish were jamming in a studio in Woodstock. Sequestered from the world, the quartet improvised for hours with the goal of finding some exciting bits to refine and embellish for its next studio album. Most of the material wound up on The Story of the Ghost, a funky, brittle album released just before Halloween the next year. But there was still some good stuff left over, so keyboardist Page McConnell took it upon himself to edit and compile it into a brief instrumental companion. They called it The Siket Disc, named after recording engineer John Siket, and released it directly to fans on their website in June 1999. An official release came via Elektra in November 2000. Only one song ever became a regular in their live sets, but the music found another purpose on tour, soundtracking the band’s late-night drives in the van.

As far as facts go, that’s all there is to it. There are nine jams, totaling just over 35 minutes altogether, culled from a period many fans recognize as the band’s prime. If The Siket Disc simply offered the best of those jams—distinguished as “Type I” when they’re following a song’s general chord progression or “Type II” when they veer into spacier territory—it would likely still have something worth recommending. But something strange happened during these sessions in Woodstock. Distinct even from The Story of the Ghost, The Siket Disc is unlike anything in Phish’s catalog. Compared to the buoyant highs they typically sought, these haunted, twilit valleys could feel like a photo negative of the band. It is the type of outlying statement that happens either with intense focus and vision or by accident: things the tape can’t help but capture.

From their moments of blissful transcendence to their goofiest in-jokes, you get the sense that, if Phish knew where any of their ideas were leading, they would have no interest in pursuing them. Like a good first date, their music aims for a natural rhythm, making each step feel somehow easy and inevitable while still advancing the action. When he formed the band in 1983, guitarist Trey Anastasio blended this impulse with conceptual songwriting and intricate, theatrical music—cerebral gestures that drew influence from oddball iconoclasts like Frank Zappa and bookish prog bands like Genesis. As the band quickly carved out a distinct voice, he loosened up, and even his virtuosic guitar playing became a tool for unity. “I feel like I’m there to be an intermediary between music that’s in the universe and the audience,” he told Guitar World in 1996. “It sounds silly, but I believe it more than I believe anything else in my life.”