To listen to early Saint Etienne records is to be taken over by the promise of youth: the sound of three wide-eyed arrivals to the big city making the most of their pop dreams. The joy of Bob Stanley and Pete Wiggs’ production stems from its refusal of simple escapism, charting a clever, side-winding path where slice-of-life charm runs parallel to outré pop fantasy. Obsolete or half-imagined zones like Finisterre, Tiger Bay, and Foxbase Alpha mapped onto the real-life texture of the Home Counties, West Country, and London itself. Sarah Cracknell leverages the easy intimacy of her voice to navigate the highs and lows of this sometimes-vivid, sometimes-cardboard scenery, her glamorous, comforting presence leading the way through Wiggs and Stanley’s fireworks.

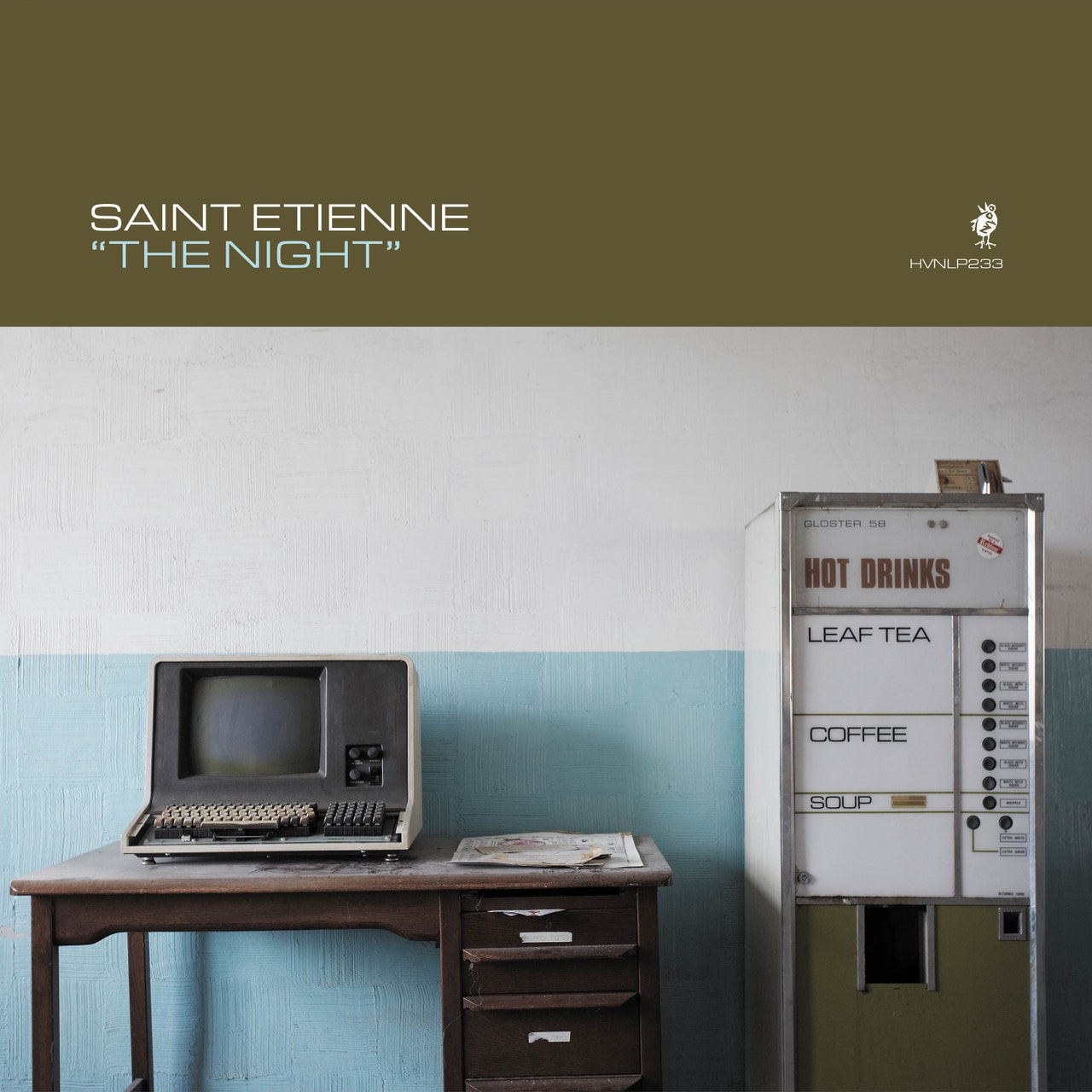

But time has a pitiless way of telescoping out, and you could almost cry at the band’s era-specific optimism and the lost world that inspired it: London still welcoming and affordable, the UK still a part of Europe, ecstasy and Concorde flights and Englishness as sources of breezy pride rather than vein-bursting reaction. “When you’re 20 or 21,” Cracknell intones with an unmistakable grain in her voice on the opening track of the group’s 11th studio album, The Night, “You have so much energy and belief.” One might read the song’s title, “Settle In,” two ways: as a rainy evening at home, or as waiting out the rest of your life. On The Night, Saint Etienne temper their boundless imagination with a sense of finality and adult knowingness, keeping the fire glowing with a full awareness of the fast-approaching cold and dark.

The Night feels like an extension and refinement of the downbeat melancholy of 2021’s I’ve Been Trying to Tell You. That record, which wove sleepy dub production and elliptical samples into mournful circles, dwelled on repetition without ever fully articulating the obvious sadness at its center. In contrast, The Night’s pivot toward ambient music dovetails with a deep world-weariness. Stanley and Wiggs evoke nocturnal scenes with an ear for creepy resonance, foregrounding the creaks, aches, and eerie frequencies that go unheard during the day. Their palette is both detailed and impressionist, conjuring a dense fog and studding it with place-markers that flicker and recede along with the music. On “Through the Glass” and “Northern Counties East,” the group soundtrack a patter of never-ending rainfall, rounding out the gloom with found percussion, pained harpsichord, and subdued guitar. At times the murk is so dense, you’d be forgiven for thinking you’d put on The Caretaker or a latter-day Burial record.