It was Sunday evening and BigXthaPlug’s mic was too low. As soon as the Dallas rapper ambled onstage, shirtless and glowering like a henchman in a children’s movie, it was clear that the mixing board was not exactly prepared for him. A deadened vocal track posed a particular problem in this case, as his crowd spilled out in three directions from an already overstuffed Gobi tent. These parallel phenomena—an overwhelming enthusiasm, not quite measurable by Billboard, for a classicist regional rapper from outside of the major label system; an apparent disregard by Coachella for rap music outside of the genre’s obvious A-list—would seem a ready-made metaphor for the festival being losing touch with a morphing music world.

It didn’t matter. BigX, whose animated style and sly taste in samples have made him a quiet sensation in hip-hop, cut through the considerable din with a husky voice as pointed and pliable under Gobi’s faux chandeliers as it is on record. What’s more is he successfully transformed the former polo grounds into a Dallas nightclub, introducing a trio of his collaborators one by one, drawing power from specificity. And so the set came to symbolize something else: a Coachella that’s been rejuvenated and refitted for an unpredictable new period in the industry, a behemoth that once again appears able to accommodate emerging acts and eccentrics in addition to streaming-certified stars.

In the wake of a two-year hiatus necessitated by the pandemic, Coachella has been dogged by reports of lagging ticket sales. While the official 2025 numbers are not yet available, it does not require a financial forensic analysis to see that enthusiasm has spiked. Anecdotally, every stage was fuller, every corridor of the grounds less passable than it’s been since the 2022 return. BigX is a uniquely magnetic figure, but on the first weekend, he was far from the only downticket act to be treated like a marquee performer.

This was despite a trio of headliners that could be described as uneven at best. Travis Scott, who was slated to anchor the Saturday bill in 2020, was given this Saturday instead. Travis is one of the most vacuous stars the major labels have ever produced, a machine for turning the work of more interesting rappers into garbled playlist slop. His high-art pretensions have influenced the most tedious rap and R&B of the 2010s and ‘20s, where stone-faced orchestral arrangements and overdetermined beat switches soundtrack verses that are stupid but never lighthearted or funny. His set, which included a pair of unreleased songs from an apparently gestating album, was dotted by other MCs’ styles, both in the sense of his craven biting and in the inclusion of his collaborations with Playboi Carti, Lil Uzi Vert, Future, and Kanye West, plus an interpolation of Drake’s “Nokia.” He dressed as if the Mad Max movies had been made to stream on Twitch.

Post Malone, who closed out the festival Sunday night, has a more legible personality, but songs that are just as anonymous and perhaps even more inane. The now svelte singer—another Dallas native, although really, he sprang from a suburban basement of the mind—has moved fully into pop-country territory, having long ago abandoned the hip-hop textures he rode to fame. (During “rockstar,” a shirtless, oddly paranoid, middle-aged man with an Australian accent asked me and my friend if “there’s a rapper onstage.” “No,” we could confidently say.) Post does deserve points, however, for insisting on an otherwise rote “you can be whatever you want to be if you follow your dreams” speech that more people should consider becoming entomologists.

On Friday night, Lady Gaga was significantly more effective. Her high-camp opera, which leaned heavily on last month’s Mayhem, was well considered and consistently amusing; two friends who were watching the YouTube livestream texted me separately to say that they were enamored. But, while Gaga is a seasoned arena performer, there is truly no way to account for the angles and sightlines of the surely more than 50,000 people who sprawled across a flat field. At times, from a distance, it felt like watching through a window as your neighbor assembles a ship in a bottle.

Fortunately, the acts just below the headlining level were exceptional. In succession, the penultimate sets on the main stage were from Missy Elliott, whose career-spanning performance was a highlight of the weekend, and not only because her UFO-themed costume was included a bicycle helmet that could have been purchased at the Target in Palm Desert; Charli XCX, who replaced Missy’s martian animations on the massive video board with a series of quick, cokey cut-ins, and played to a positively raucous crowd; and Megan Thee Stallion, whose execution recalled the freestyle videos for which she became famous. The default parlor game at Coachella is to speculate about who might be a viable headliner in the future; any of these three women could have held down her own day.

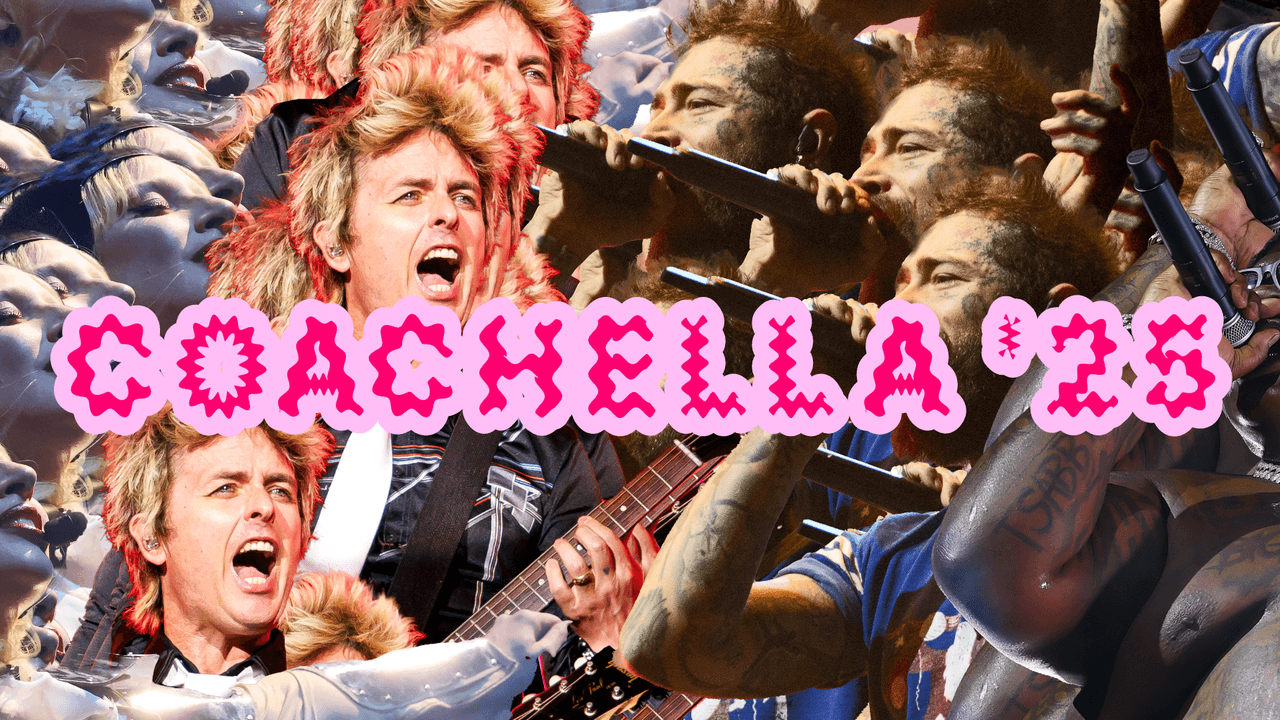

The asterisk in the paragraph above is because Charli’s Saturday evening set was actually followed by not only Travis Scott at midnight, but Green Day at 9:05. On this year’s bill, Green Day is technically listed as the Saturday headliner, with Travis Scott at the very bottom of the poster (the language being “Travis Scott Designs the Desert”). This marks the third year in a row, following Calvin Harris in 2023 and No Doubt last year, that the festival has essentially added a stealth fourth headliner.

Billing aside, Green Day was expert and efficient, anti-MAGA “American Idiot” update and all. Despite the band’s unshakable association with the pop (and political) culture of the ‘90s and 2000s, neither their set nor the festival writ large trafficked in nostalgia in the same way, or to the same degree as last year’s edition. Like Billie Joe Armstrong et al., the Misfits, who played at the Outdoor theatre between Green Day and Travis Scott’s turns on the main stage, eschewed “remember-when” for their typically confrontational mode. It was a noted departure from not only No Doubt’s sepia tones, but last year’s zombie Sublime set and 2023’s surprise performance by Blink-182. The most purely nostalgic moment of the weekend was T-Pain’s Saturday-evening barrage of Bush-era hits.

A thing you have to understand about me is that I’m a Coachella optimist. With the significant caveat that I do not have to pay for admission (this year, weekend 1 general admission was $649, VIP more than double that), I’ve loved going every year for the past decade, and defend it against jokes about “hipsters” and so on. There’s an alien quality to the desert; seasoned attendees know that 100-plus degree weather should not fool them into being caught without a jacket when that heat burns off and the temperature plummets. It’s not exactly a sensory deprivation chamber—in fact, quite the opposite—but it reorients your senses enough to receive things in a different way. Consequently, in addition to the acts you might earmark as soon as the lineup is posted, it’s all but inevitable that you’ll stumble into a handful of sets that end up being among the best live music you see all year.

I say all that to say that Benson Boone is horrible, just godawful, the kind of act that makes you wonder if this whole medium has been worth it. His main stage set, at 7 p.m. on Friday—a preposterous slot for him—was nine absolutely insipid originals that seem designed to soundtrack tearful front-facing confession videos followed by a galling (and inexplicably Brian May-assisted) cover of “Bohemian Rhapsody.” I didn’t love it.

But atrocities like that were rare. Beth Gibbons’ gentle solo set, Saturday night in the Gobi tent, was enrapturing; the following night, in Mojave, Kraftwerk made a convincing argument for themselves as one of the most influential acts of the last half-century. It was a banner year for surprise guests: Queen Latifah with Megan Thee Stallion; LL Cool J with the L.A. Philharmonic; Project Pat with his Three 6 Mafia compatriots; Tyga, 2 Chainz, Roddy Ricch, and others with Mustard; Billie Eilish with Charli; and Bernie Sanders, who was rushed from a rally in downtown Los Angeles to introduce Clairo, among many others.

The most prolific guest was Danny Brown. The Detroit rapper came out for A. G. Cook Friday evening in the Gobi tent and for April Harper Grey, aka underscores’ Saturday afternoon in the Sonora tent, the often half-filled space that has quietly become the venue for many of Coachella’s most arresting performances. While both the above Danny-assisted sets were impressive, his turn on Friday night in Sonora with HiTech, the ghettotech trio also from Detroit, was the capper on what was one of the weekend’s two best sets, a truly singular mutation of that city’s rap and club music traditions.

HiTech’s only competition came from that group’s diametric opposite. Where they had bombarded Sonora with balletic drum programming and a delirious array of video clips—bits of history and ephemera sewn together in a way that accentuated the seams even as they were rendered unimportant—Darkside, who played Saturday night in Gobi, was tonally unwavering, their set a pressure cooker with no release. For more than a decade now, Nicolas Jaar and Dave Harrington have been among the most captivating live acts in the world; the Gobi show, which comes at the end of a tour that has also included drummer Tlacael Esparza, was irreducible, elemental.

Things have changed a little around the fringes, in mostly trivial ways: the once-ubiquitous pedicabs, which ferried guests from the festival grounds to the distant parking lots, are gone, perhaps deemed too dangerous; the mid-2010s “brand activation” boom has ebbed somewhat; the speakers seem dialed louder this year. The parking lots themselves ran smoothly, but the surrounding streets were worse than ever, clogged by the police departments from four municipalities plus county sheriffs, who rerouted traffic in different, always byzantine ways each of the three days. But while it’s fair to be cynical about anything so massive and so commercial, the festival feels as if it’s once again the most vital version of itself.

Walking across the grounds after the Prodigy’s Friday night set in Mojave, a friend and I found ourselves amused by Maxim’s eager announcement from the stage that he was excited to be “on the West coast.” Sort of, we said—this country is so big, so strange, so deserted. We started to debate how long it would take, right at that second, to drive to the ocean, then agreed it was impossible to know for sure.