In 1994, on an album called Minimal Nation, Detroit’s Robert Hood stripped Motor City funk to its bones. Most of its tracks were made of little more than lithe, swinging drum programming and solitary synth patches that glistened like oil slicks; it’s generally considered the origin point for what came to be known as minimal techno. In February of the same year, more than 4,000 miles away, a taciturn young Finn named Mika Vainio took an even sharper scalpel to the same ideas. His debut album, Metri, couldn’t be more skeletal if it were a laboratory specimen. Where there are drum machines, they merely thump and hiss; his custom-built tone generators glisten like icicles and roar like buzz bombs. If Hood’s album represented minimal techno’s ground zero, Vainio’s was its ground Ø.

Vainio would go on to become best known as one half of Pan Sonic, a duo (with Ilpo Väisänen) that, from the early 1990s until its dissolution in 2009, waged a scorched-earth campaign against electronic music’s staid conventions. But it was Vainio’s Ø alias—after a symbol signifying absence in a number of contexts, from math and geometry to linguistics—that would be his longest-running project, evolving from those brutalist techno origins to encompass a wide array of electronic techniques and soundscapes.

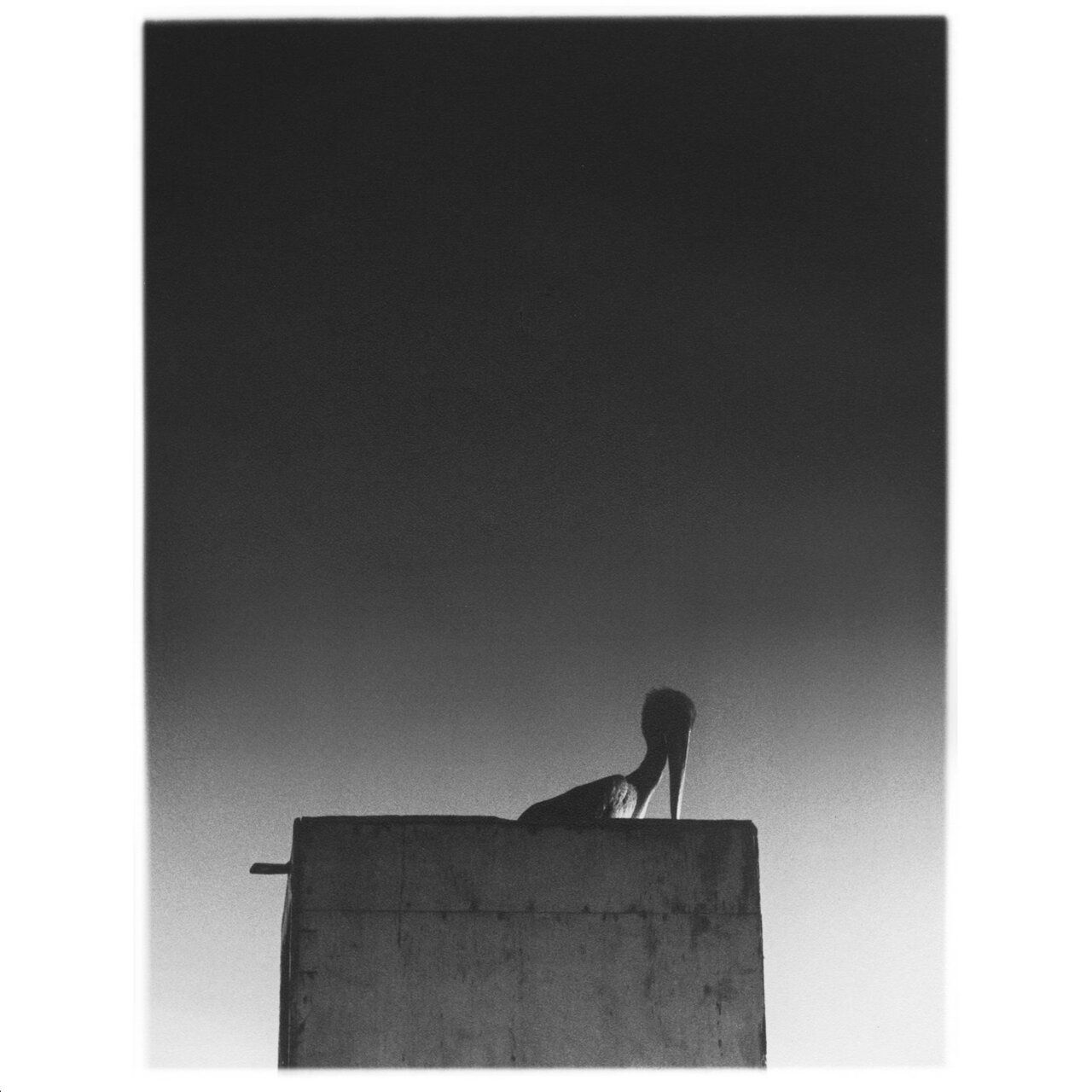

In addition to many solo and collaborative albums under his own name, Vainio released eight albums as Ø until 2017, when he plunged from a cliff in France. He had been at work on a ninth Ø album for three years at the time of his death. Working from notes he left behind, Tommi Grönlund, his friend and founder of the Sähkö label, and Rikke Lundgreen, Vainio’s former partner, compiled the material into Sysivalo, his final album. (According to Lundgreen, Vainio had already decided upon the album concept, title, track order, and even cover art.) The title—a portmanteau meaning something like “charcoal light”—is evocative and fitting. Vainio’s music often felt like an apocalyptic clash between being and nothingness, but on Sysivalo, darkness and light flow together in ways that are unusual for his work, evoking a dynamic mixture of vulnerability, tenderness, and grace.

Vainio’s music could sometimes sound like he had jacked directly into an electrical substation, but his palette here is soft and tufted. Distant thunder takes on a purplish pastel hue, misted with white noise. There are few hard attacks and even fewer moments where the levels bleed red. A bite-sized quality distinguishes these 20 tracks, which run shorter than he typically worked. Vainio’s enduring interest in capturing the vastness of sound is distilled into pieces that feel both atmospheric and tactile, like cupping small clouds of colored smoke in your hands. Yet there’s little doubt that Sysivalo is envisioned as an album—a single, overarching work, rather than a collection of stray pieces. A ruminative mood pervades the hour, and tones and themes frequently repeat. The drawn-out foghorn blast that opens the album with “Etude 1” reappears, whittled to a fine point, in “Etude 5,” and turns up again nine tracks later in “Aine” (“substance”), threading the album with a faint sense of deja vu.