Tolstoy said that there are only two stories: “a man goes on a journey” and “a stranger comes to town.” Superman happens to be both: a square-jawed every-Adonis from middle America who is, in fact, an alien. He has to leap over coastal skyscrapers and prop them up when they teeter over children and widows, but he crams his preposterous frame into phone booths to don his costume in secret. The constant pressure to conceal his identity makes him a stranger to most of his loved ones and endangers those few who know the truth; he’s not quite of his adopted world or of the planet he came from.

Because he’s virtually invincible, Superman stories only work on a dramatic level if they lean into this cycle of disillusionment and self-discovery. James Gunn’s new vision for the character (simply: Superman) is built around a clever gambit that fractures his sense of self: the video message his alien parents sent with their infant on a spaceship bound for Earth, long thought to be damaged, is reconstructed only to reveal a nefarious intent rather than the benevolent one he’s always inferred.

Gunn is a veteran of Hollywood’s comic book boom, having directed the Guardians of the Galaxy trilogy for Marvel before being tapped by Warner Bros. to oversee their DC adaptations. Like the Guardians movies, Superman is breezy and colorful, closer in spirit to Tim Burton’s Batman than to Christopher Nolan’s. This is probably the better tonal register for the character—it’s at the very least a welcome corrective to Zack Snyder’s drab, dour Man of Steel, which in 2013 reached the nadir of post-Dark Knight superhero self-importance.

But Gunn takes this lightness and tries to bend it in every direction imaginable. This is a film about the beauty of chosen community and the sterilizing nature of living as a transplant; the need for rigorous ethics and the virtue of blind faith; tech and Trump and Musk and, yes, Gaza. The geopolitics are at once surprisingly clear-eyed and frustratingly naive—the villain’s vapid girlfriend is a punchline before, during, and after her stint as a selfless informant. Gunn is the sole credited screenwriter, and that makes sense: These feel less like thrice-approved studio notes than the markers of a hyperactive mind who has imagined his hero in innumerable real-life scenarios and wants to leave it all out there on the screen.

Superman was created in 1938 by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, a writer and artist, respectively, who met in high school during the Depression. Siegel had self-published a short story called “The Reign of the Superman”—a parable about a homeless man who is pulled from a bread line and duped by a craven scientist into drinking a potion that gives him magical powers, which he uses for his own, selfish ends. He tries to take over the world, only to return to that same bread line when the powers wear off.

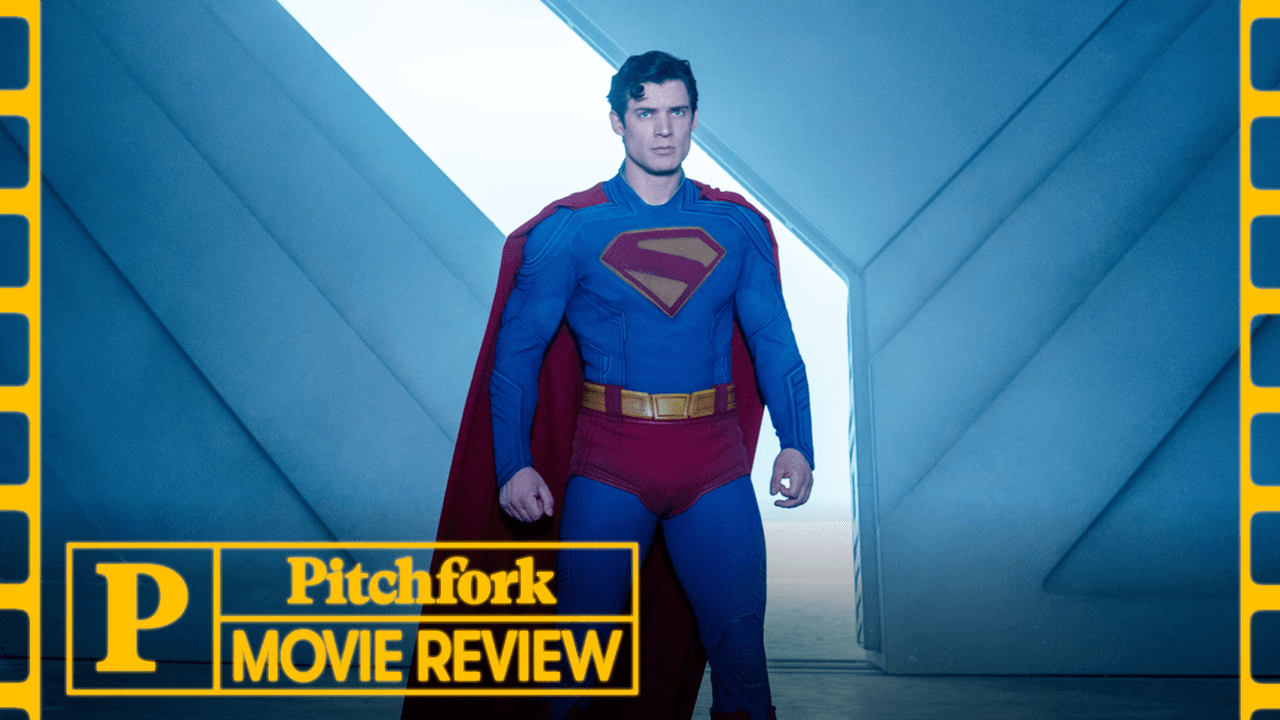

The acidity of Siegel’s original title has rarely made it into the comics, movies, or other properties starring the caped iteration. Unlike with Batman, which has lured major stars, the directors and producers of Superman movies have generally cast young, strapping unknowns, a certain blankness as the baseline for both Kal-El and Clark Kent. Here, David Corenswet plays him more or less down the middle: earnest and burdened and aww-shucks guileless even when he bristles at Lois Lane’s (The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel’s Rachel Brosnahan) rule-following.

While this Superman never really establishes the Daily Planet offices as a functioning ecosystem—to say nothing of Metropolis, which seems like approximately four city blocks’ worth of recurring extras and a bunch of office buildings outfitted with stunt glass—Corenswet plays a kind of uneasy routine that feels finely calibrated. When the world is thin, the sets a little shoddy, Corenswet is there to make them feel inhabited by humans, or at least something close.

Which makes it a shame when the film frequently descends into CGI so pat and cheesy as to make any sort of emotional stakes irretrievable. Oftentimes, the elements don’t even bother pretending to move in anything resembling a natural way; at points there are entire frames that could be isolated, stripped from context, and credibly presented as being from an animated movie. Superman was shot by Henry Braham, who previously worked with Gunn on the last two Guardians movies and The Suicide Squad. Despite the generally agreeable color grading, the sequences in the “pocket universe” are every bit as gloopy, washed out, and illegible as the bulk of Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania, a film so ugly it triggered wholesale reconsiderations of the Marvel franchise.

The rest of the cast comes off much worse than Corenswet, albeit in a way that indicts Gunn more than any performer. Nicholas Hoult, in particular, is hung out to dry, his Lex Luthor seemingly played with all the conviction of your coworker miming a nine-iron swing as he waits for the photocopier to finish. He’s not sleepwalking; he’s tuned to a different frequency. Brosnahan is competent, if too much of a stock character in the Planet offices—and wonderfully layered in her domestic scenes with Corenswet—but is swallowed entirely when Lois is meant to move the plot forward. In those moments, Gunn forgets to write her as a character. Pruitt Taylor Vince and especially Neva Howell play his Kansas parents with the sort of dripping condescension that is probably inevitable when the script tells a 60-something woman to tell her son there’s something he might want to watch “on the box.”

Though the plot is remarkably straightforward for a modern blockbuster, it’s difficult to predict the stakes of each scene due to the sheer incoherence of the performances. Moreover, the confused tone of the third act should not exist in a film that deals exclusively in primary colors. When the invented Balkans-esque country—with its American-allied and -armed military of lighter-skinned men and women—prepares to invade the invented Central Asian-esque country and kill its clearly impoverished, darker-skinned civilians, Superman has the wrong kind of anything-can-happen spontaneity: We are acutely aware that we could see a child beheaded by a drone—or have to endure small talk with a flying Nathan Fillion.

It might sound like I’m sneering at Superman for not setting out to be a docudrama about a real-world genocide. I’m not. What’s maddening is Gunn’s inability to let his characters sit in discomfort. At the first sign of resistance, the occupying army backs down, the occupied population unambiguously liberated; when one of the world’s richest men is revealed to have sinister plans, he is immediately decried; amid a global rejection of Superman, news anchors risk their safety to get behind their desks and announce that we’ve all got wrong, he’s still the man. Everyone goes home in a limousine. It’s neat and clean and not at all how the world works, even in most comic book movies. At least the man at its center, already apart from you and me, seems ready to strike out for somewhere new.