‘Stop the War’: The Forgotten Black Voices Who Protested Vietnam in Song

The emotions that stampede through the 23 tracks on Stop the War should be familiar to anyone who’s heard songs objecting to the Vietnam fiasco of the Sixties and Seventies. Soldiers yearn to see their lovers or families again or beg those partners to stay faithful; protesting voices call out for troops to be brought home or simply never be sent into battle at all. Some of the voices are angry; others are dipped in anguish.

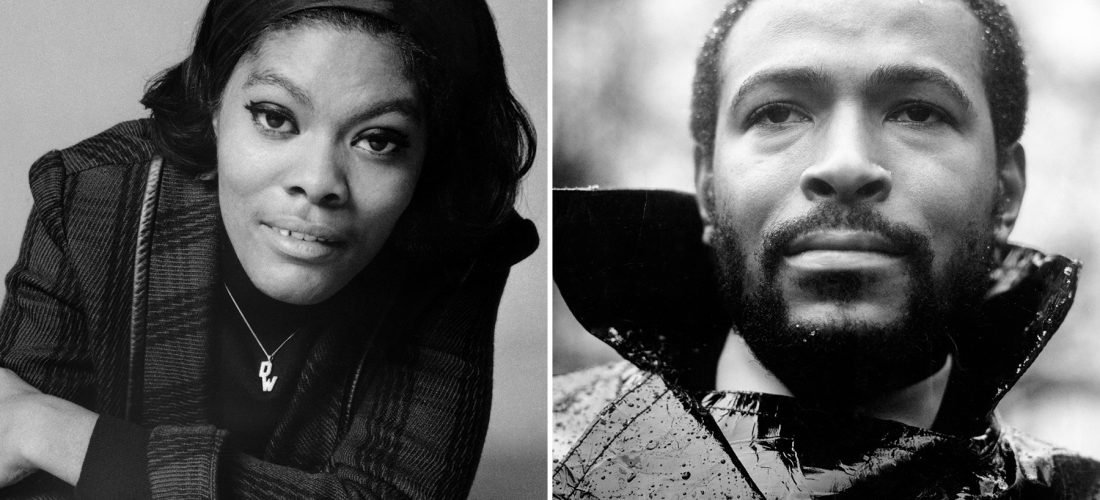

What sets this anthology apart from nearly every other collection of anti-war songs, though, is race. With a handful of exceptions — Edwin Starr’s “War,” Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” Stevie Wonder’s “Front Line,” to name a couple — songs chronicling the horrors of war and Vietnam tend to be associated with white artists. Stop the War: Vietnam Through the Eyes of Black America 1965-1974, a revelatory new collection from the British label Ace, makes the case that people of color were equally distraught, angry and rattled by the war, and expressed those feelings in songs as much as their rock or folk counterparts.

As much if not more so than others, the black community had reason to be angered, worried and freaked out by that conflict. More African-American men were drafted during Vietnam than during any previous American war, resulting in a quarter of combat troops in Vietnam being black — even though, at the time, the black population in the U.S. was around 10 percent. In 1965 alone, black soldiers accounted for one quarter of the combat deaths in Vietnam.

The wide-ranging impact of those stats on the community is heard in the array of styles on Stop the War. There is smoothly elegant pop courtesy Dionne Warwick’s “I Say a Little Prayer,” its Hal David-penned lyrics meant to imply the voice of a woman hoping her soldier-partner is safe. The more obscure but worthy “Wish You Were Here with Me,” by the Washington, D.C. trio the Fawns, approaches the elegance of those Bacharach-David-Warwick records. The Chairmen of the Board, best known for their desperately pleading 1969 hit “Give Me Just a Little More Time,” are represented here by the huskier “Men Are Getting Scarce,” which recalls the tougher, socially aware Motown hits of the time.

Stop the War also shows how anti-war sentiments made their way into blues (Allen Orange’s ornery “V.C. Blues”) and something approaching gospel (the Mighty Hannibal’s “Hymn No. 5,” which feels like a funeral march overseen by a soul shouter). Produced and written by the monumental duo of Isaac Hayes and David Porter, the Emotions’ “Going on Strike” bolsters the sentiment of its lyrics — women who vow to resist temptation while their men are away — with a Stax groove that in another world would have made it a hit. Gaye’s obscure “I Want to Come Home for Christmas,” sung in the voice of an American POW hoping for release by the holidays, was ultimately shelved when “Motown’s Quality Control department decided that it was far too downbeat to bring any seasonal cheer to anyone,” according to compiler Tony Rounce in his liner notes. (The song’s lack of a grabby hook could have been another reason.)

The collection has an emotional range and depth that matches its musical scope. There are songs in which soldiers describe the men they saw killed in the same foxhole (Charles Smith and Jeff Cooper’s “Glad to Be Home”), ask their partners not to stray (Michael Lizzmore’s plush but aching “Promise That You’ll Wait”) and wax optimistic about the day they can leave the frontlines (Artie Golden’s fairly sunny “I’ll Be Home”). In Joe Medwick’s downright perverse “Letter to a Buddie,” the narrator teases a soldier by telling him all the things happening at home without him: his brother-in-law is wearing his favorite suit, a friend has sold his golf clubs and movie projector, and local guys still whistle at his wife when she walks down the street. “Don’t forget to write!” Medwick chimes in at the end. Set to cocktail-lounge soul, the song was intended to be funny, but it’s as brutal as the most forthright anti-war commentary.

Understandably, though, humor of any sorts is largely missing from Stop the War; if anything, these are among the grimmest and bleakest anti-war songs you’ll ever hear. Dr. William Truly Jr.’s “(The Two Wars of) Old Black Joe” is a spoken-word piece set to a somber shuffle about a black soldier who isn’t allowed to be buried in an all-white cemetery until a judge orders otherwise. Outraged whites dig up their dead relatives from the same graveyard to move them to another, realize there isn’t a backup cemetery nearby, and are forced to return and rebury their dead “next to old … black … Joe,” Truly spacing out each word for maximum impact. (For the sake of trivia, that song was released on an obscure indie label owned by Kenny Rogers’ brother.) With Pop Staples’ tremolo guitar rippling through it, the Staples Singers’ cover of Bob Dylan’s “John Brown” — the tale of a mother who greets her returning-soldier son at a train station, only to find him horribly disfigured — is even more disturbing than Dylan’s own version.

Stop the War ends with “Home to Stay” from R.B. Greaves, the pop-soul singer best known for his zesty 1969 hit “Take a Letter, Maria,” about a black executive dumped by his wife who decides to “start a new life” with his Latino secretary. Musically or lyrically, “Home to Stay” isn’t nearly as peppy: Greaves adopts the role of a soldier who’s returned to his neighborhood and sees his family and girlfriend — “as they lay me down in this cold, empty ground.” The song ends the collection of an appropriately somber note: Take another letter, Maria, because your man is dead.