From the moment Puff said it, it felt wrong. When the disgraced Bad Boy Entertainment founder rapped, on The Notorious B.I.G.’s “Mo Money Mo Problems,” that “ten years from now, we’ll still be on top,” it was in that flat preening monotone. Hip-hop’s commercial trajectory appeared to be such that he and his peers might keep accumulating yachts, but the dynasty he envisioned never seemed credible. By the time that song was finally released as a single, on July 15, 1997, Big had been dead for more than four months, and Puff’s Police-sampling elegy, “I’ll Be Missing You,” was already a No. 1 hit. In the video for “Mo Money,” when Puff raps the “ten years” line, he’s standing next to Mase in one of those glittering wind tunnels; they flit between different outfits and setups, their shimmying intercut with a team of dancers given slightly more robust choreography. Eventually we see archival footage of Big, presented with all the care and solemnity of the Terminator 2 clips that play as you wait in line at Universal Studios.

Big’s assassination left a vacuum in New York hip-hop. Jay-Z and DMX would move to fill it, each succeeding in different ways; even with the Wu-Tang momentum waning, Ghostface was regrouping to prepare for Supreme Clientele; Big Pun was getting acrobatic; underneath all of this, Zev Love X had reemerged, rapping with stockings over his face at the Nuyorican Poets Café as MF DOOM. At every strata, in little venues with sticky floors and yawning boardrooms alike, artists seemed to be competing not only for commercial supremacy, but for the right to drag the genre, and the city, in the creative direction they saw fit.

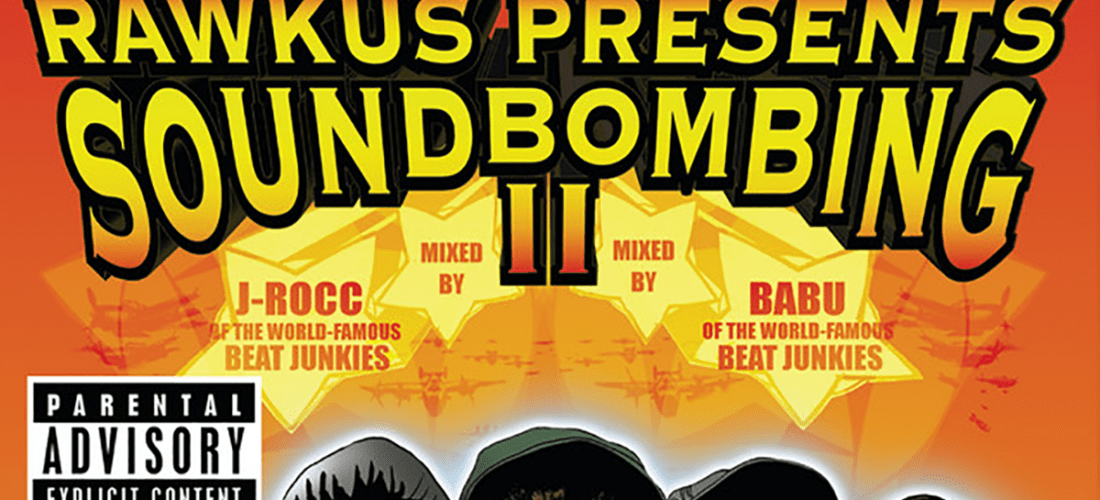

One week after “Mo Money Mo Problems” was issued to radio, Company Flow’s Funcrusher Plus became the first release from an independent label called Rawkus Records. The trio, comprised of rapper-producers El-P and Bigg Jus and DJ Mr. Len, had sold more than 30,000 copies of their 1995 vinyl-only EP Funcrusher without any label support; when Rawkus founders Jarret Myer and Brian Brater approached them with the financial backing of their friend James Murdoch—he of those Murdochs, the Murdoch Murdochs—they felt they’d have the creative latitude they needed to expand Funcrusher into something even more bludgeoning and unsettling. The expanded album opens with a too-sly extended joke about child molestation, then a quip about 2Pac being shot at Quad Studios in 1994 (this being less than a year after Pac was eventually killed in Las Vegas). Funcrusher Plus is often brooding and brutal, El-P’s production ingenious and totalizing. While the majority of its verses are de rigueur battle raps, the album sounds like one particularly grim vision of the future.