John Martyn was, in every way, a hard man to pin down. He was a gregarious, rambunctious guy who loved to booze and brawl—he beat up Sid Vicious after the punk singer insulted him during a poker game. Equally talented as a singer, songwriter, and guitarist, he wasn’t quite virtuosic at any one of these things. He was an integral member of the flourishing and shaggy British folk movement of the late 1960s and early ’70s, yet his most acclaimed music can’t really be characterized as “folk” at all. His plainspoken lyrics aren’t as idiosyncratic as Richard Thompson’s mordant drama or his close friend Nick Drake’s tender eloquence, to name a couple of his contemporaries. So what makes Martyn special? It’s his unmatched ability to tap into a specific aspect of music-making, one whose cultural currency has peaked in recent years. Martyn was the master of vibes.

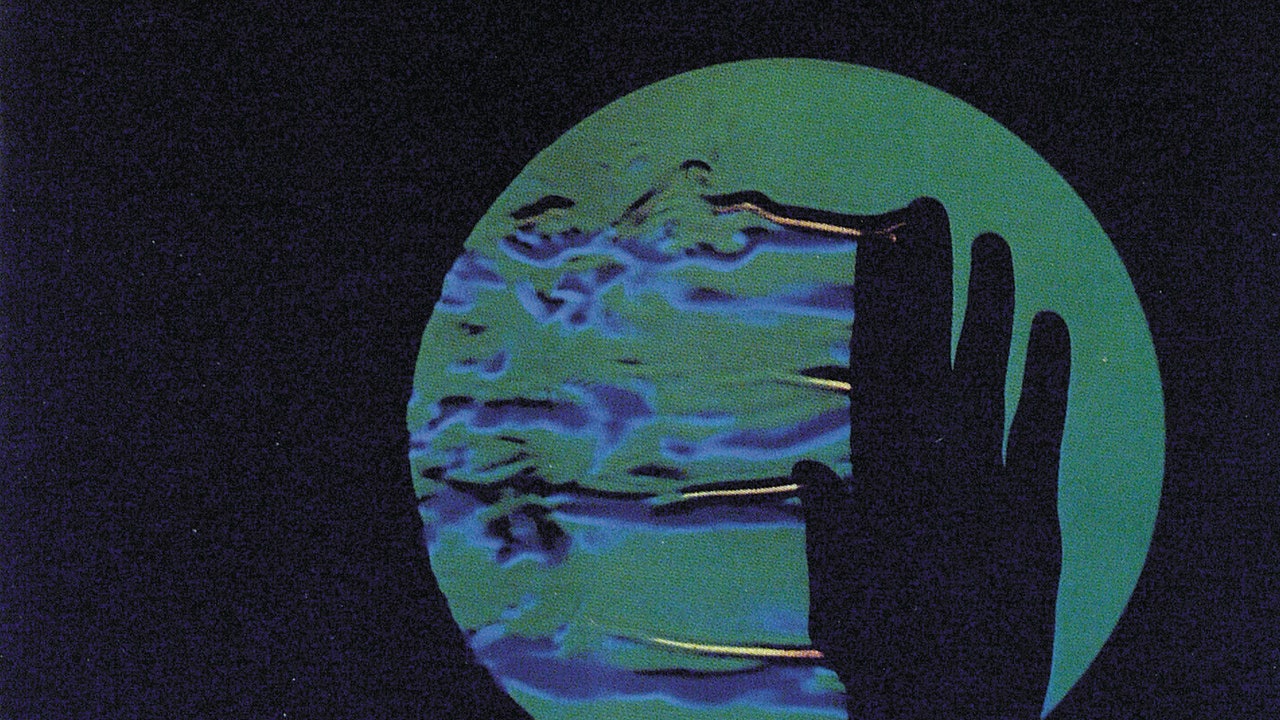

To pedants and spoilsports, “vibes” is either a meaningless word or an expression of meaninglessness, a rhetorical crutch of the inarticulate to convey aesthetics, charisma, or energy. But vibes are real. As professor Tom F. Wright argues in The Atlantic, the term has roots in the 19th century, “older esoteric traditions that described social relations as ‘vibratory,’” later revived via the “good vibrations” of the hippies in the ’60s. For Martyn, “vibes” undoubtedly describes an ineffable mood or sensibility, a “tune in, turn on, drop out” mindset undergirding a preternatural cool. Yet it’s also music full of actual vibrations—keyboard twinkles, frenetic woody basslines, scuttling percussion, and reverberating cyclones of guitar strums, unmoored and seemingly levitating in the ether, coiled by a burly, warm voice slurring words into splatters and smears.

It’s a testament to Martyn’s technique and fundamental training that this circuitous architecture never sounds remotely off-putting or inaccessible. In his music you can hear the autumnal warmth of Nick Drake, the soul-searching intensity of Van Morrison, the kaleidoscopic exploration of electric Miles Davis, and as Martyn frequently acknowledged, the clacking, searing earth-fire of Pharoah Sanders. What all these artists share is an astral perspective, a supernatural ability to divine music that soars in atmospheric planes. For Drake it was an Orphic sense of the elysian; for Morrison it was repetition as a means of attaining the mystical. Yet where Drake and Morrison projected inward, and where Davis and Sanders billowed outward, Martyn’s music seems to move from the inside out, or omnidirectionally. But it’s not “free”—it has structure and melody, intimacy and soft edges. It possesses a quality that is hard to isolate or map. It’s just… vibes!