Like a lot of American kids born in the early 1980s, I first heard Pavement on alternative-rock radio in the back of a car. The car was a Saturn going uphill toward the stop sign on Birch Hill Road; it is as clear and romantically enhanced as my dad’s memories of hearing the Beatles. The song was “Cut Your Hair.” I instantly identified it as both a comfortable fit and yet something totally different, neither the sex cries of Stone Temple Pilots nor the wounded diaries of the Smashing Pumpkins. It was messy but catchy, music that had metabolized the rebellion of punk (“Career, career, career,” the singer shouted, somehow not angrily) but also felt boyish and joyful and refreshingly—almost subversively—pain-free.

Alternative to what? Nirvana was already a platinum-selling band; in the wake of Nevermind, artists as superficially uncommercial as Sonic Youth and the Breeders were given a shot at a market share their predecessors in the American underground would have never dreamed of. The gold rush was on, if not already over; “alternative” was just another way to signal the onramp to the mainstream.

The album “Cut Your Hair” was on, 1994’s Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain, peaked in the nether reaches of the Billboard 200, well below what the band’s spiritual predecessors R.E.M. had achieved by a similar point in their career. Singer Stephen Malkmus said he’d wanted the music to feel like classic rock—that glory, that ease—but good. To hardasses who mistook angst as the foundation of creative insight, they sounded like college boys coasting on an excess of privilege and charm. Critics loved them; most people didn’t care.

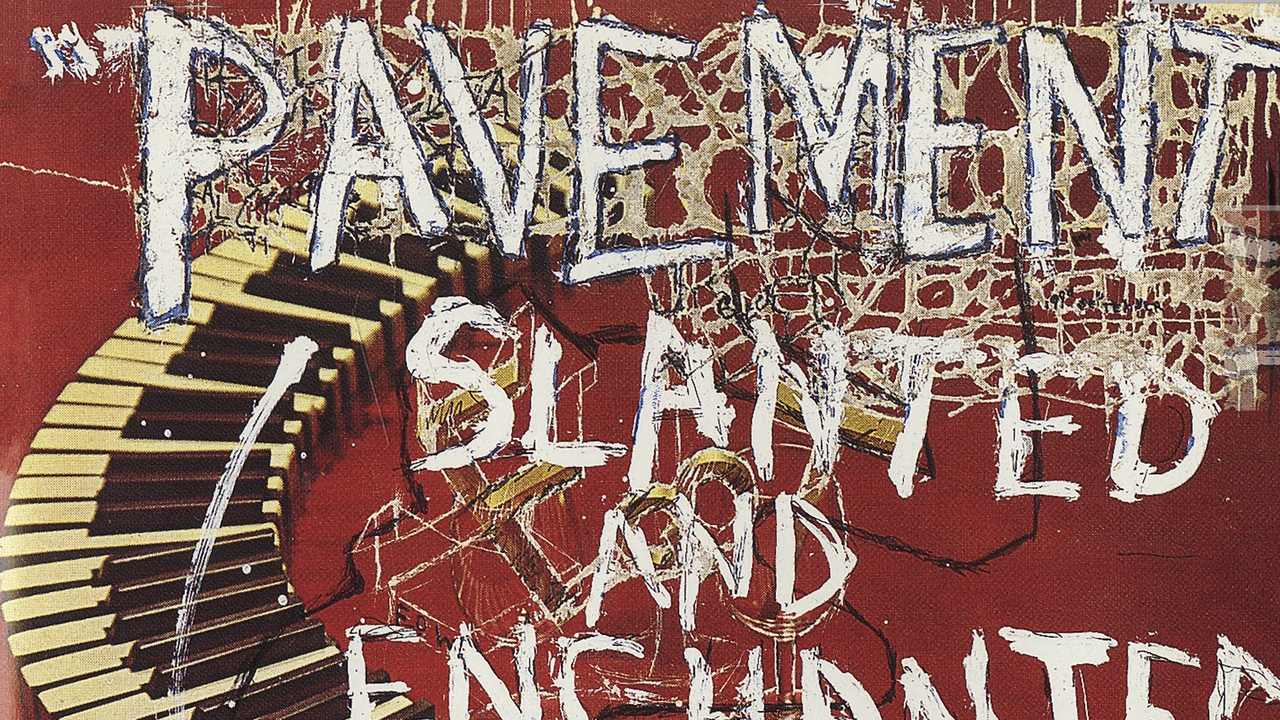

Where Crooked Rain felt cool and extroverted, the band’s first album, Slanted and Enchanted, was further off the beaten path. Certainly, Pavement wasn’t the only early-’90s indie band to turn noise into something like pop. But the noise of Slanted felt more like a byproduct of distance or age than a corrosive agent, the grain of an old photograph or tracking lines on a tube TV; noise not as a reflection of industrial modernity but as something vulnerable and soft and flaky, like memory.

The sweet songs are tender and penetrating, the less-sweet ones radiant with the messy conviction of a street preacher; the climactic lines—“Minerals, ice deposit daily/Drop off the first shiny robe” from “Summer Babe”—dependent not on the logic of their language but the passion of their delivery. The album’s title had famously come from the American poet Emily Dickinson, who wrote, “Tell all the truth but tell it slant —/Success in Circuit lies,” a line whose quiet threat to the supremacy of romantic disclosure should probably be written into the national anthem. For me, Slanted will always conjure the random, epiphanic quality of sudden light: the bolt in the sky, the gold in the pan, the fireflies in the field.