No one listens to Arthur Russell just once. (Well, almost no one.) If you have heard his music, it is likely that you have internalized his singular voice and unique melodic sensibility, folded them into some innermost corner of your being. He has this effect on people, despite the fact—or maybe because of it—that the vast majority of his fans never heard a lick of his music while he was still alive. Yet this pair of decades-old live recordings reveals Charles Arthur Russell, Jr., gone now 33 years, as you have rarely, if ever, heard him before: just cello, the electrical heat of the microphone, the buzz and sway of a few pedals, a cocoon of empty space around him—and that voice, unmistakable, ethereal yet embodied, both distant and impossibly close, as familiar as the voice in your head.

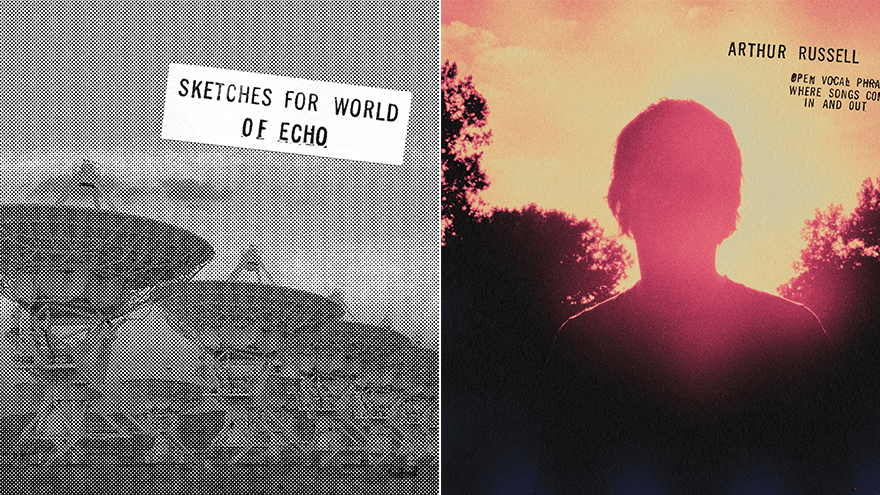

These reissues come from two tapes recorded at Phill Niblock’s Experimental Intermedia Foundation, a homey loft space in lower Manhattan where Russell frequently performed. He recorded the first on June 25, 1984, at a performance billed as Sketches for World of Echo (admission: $2.50), and the second 18 months later, on December 20, 1985. Steve Knutson’s Audika label—which in collaboration with Russell’s partner, Tom Lee, has given the world far more posthumous work from the artist than he ever released in his lifetime—first put out Sketches for World of Echo digitally and on cassette in 2020; the second live set, now titled Open Vocal Phrases Where Songs Come In and Out, remained unheard until now. While available separately on Bandcamp and streaming platforms, both recordings have been paired on a 2xCD release, which is appropriate: They feel like segments of a single continuum, snapshots of a long, unbroken moment.

These are not unplugged sessions, exactly; Russell was an inveterate tinkerer, and in both sets he fleshes out his cello and voice with a modest battery of effects pedals—stereo delay, reverb, distortion—and a rudimentary tone generator. Yet rather than obscure his playing and singing, those add-ons only seem to heighten the sensation that we are sitting alone in the room with him. There is an uncommon purity to these recordings that suits the guilelessness of his music; it is rare to feel like you have been granted such a direct line to an artist’s mind at the moment of creation. He would later stitch segments from both nights into the 1986 album World of Echo, combining them with material recorded at Battery Sound studios, and some elements are echoed elsewhere in his catalog in radically different forms—the avant-disco masterpiece “Let’s Go Swimming,” famously mixed by Walter Gibbons; the Nicky Siano-produced disco anthem “Tiger Stripes,” which Russell recorded under his Killer Whale alias—but by and large, these recordings are less collections of discrete songs than extended fantasias, improvisational meditations in which lyrical hints and brief melodic figures dissolve in the ceaseless onward flow.