As Cyndi Lauper leaped around singing “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” on The Tonight Show in 1984, it seemed like she might never put down the microphone. After she kicked off her stilettos, danced with her backup singers, sprinted back and forth repeatedly from the monitors at the front of the stage to the drum kit in the rear, and belted out the final refrain enough times to ensure that every spectator would be singing it for the rest of the day, the song only ended with the musicians stumbling one by one to a halt: some of them ready to wrap up, and others apparently willing to continue accompanying Lauper until the end of time.

“If I wasn’t doing this, Johnny, I might’ve been a brain surgeon or a rocket scientist,” she told Johnny Carson afterwards, refastening her heels and adjusting her jewelry. “A visiting professor at Harvard,” he offered in return. Though the host’s response had a note of condescension for this young woman singer who’d just spent the last several minutes exalting the virtues of a good time above all else, it’s clear that she was in on the joke. There would be no rocket science or brain surgery for Cyndi Lauper: not because she was too fizzy and fun-loving to learn how, but because she was born to perform.

There are only three original songs on She’s So Unusual, Lauper’s 1983 debut. Years before its release, she’d been the frontwoman of a cover band. She didn’t need to write songs to express her immense natural talent as a performer. Instead, she used the words of men to illuminate her assertive vision of womanhood, each impassioned yelp a detonation inside its source material. Lauper waffled about ascribing deeper feminist meaning to songs like “Girls Just Want to Have Fun,” but there’s a gravity in her vibrato that’s hard to shake. She brought the weight of her past—her childhood growing up in an abusive home, her battles against male industry gatekeepers—into that music. Her voice walks the line between desperation and the self-assurance she gained from playing in bars night after night. It begs, with its technical skill, to be taken seriously, yet is softened by Lauper’s cartoonish inflections that garnered frequent comparisons to actresses like Bernadette Peters more than contemporary female rockers like Pat Benatar. “That’s all they really want,” she belted on “Girls” with more than a hint of indignation, as if to say, Is that seriously so much to ask?

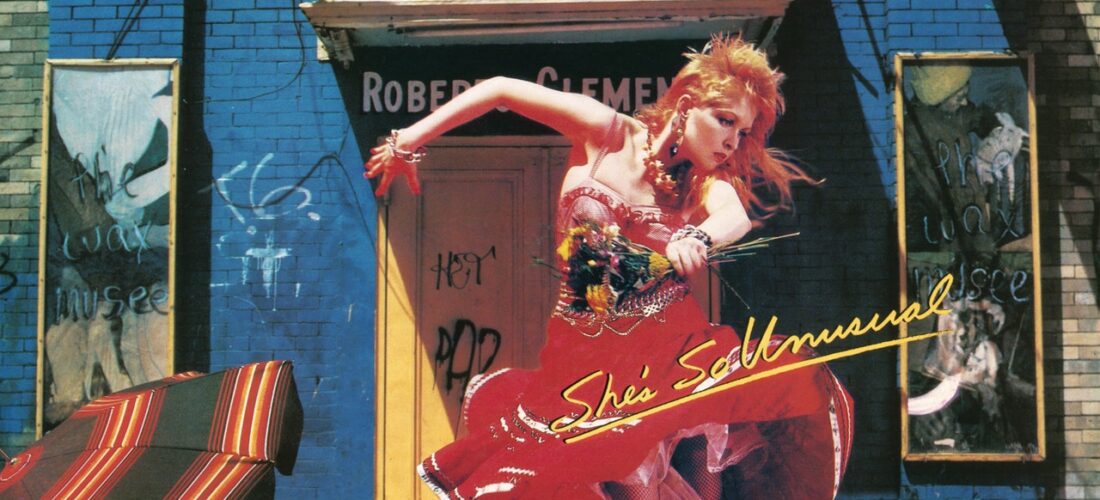

With She’s So Unusual, Lauper shoehorned rebellion into the familiar, both musically and visually: Who else would play a 1920s song written for the real-life Betty Boop wearing tulle fingerless gloves and a mullet? With her taste for synthesizer-driven disco (she apparently met with Giorgio Moroder once, but he seemed to dislike that she called him “George”), Lauper helped to usher in an electronic era for popular rock. After decades of being rejected by her peers, local bands, and record labels, Lauper wanted not just acceptance, but an embrace, of not just her quirks, but of eccentricity itself. She’s So Unusual imagined a world where women danced through New York in ruffle skirts and combat boots, partied with a sense of purpose, and were just as powerful at their most vulnerable as their most ferocious.