Richard Branson on signing Sex Pistols and the state of the music industry: “The more the establishment attacked us, the more we enjoyed it”

Sir Richard Branson has spoken to NME about the pressure he faced for signing Sex Pistols – with comparisons with Kneecap today – as well as sharing his thoughts on the shifting landscape of the music industry.

The mogul and business magnate was speaking to NME ahead of his recent win at The Ivors Academy’s inaugural Honours ceremony in London, where he was recognised for his “extraordinary contribution to music through Virgin Records, signing groundbreaking names and giving songwriters the freedom to innovate and succeed”.

Branson said his honour was for “lots of people who helped build the Number One record label in the world” and that the biggest privilege of all was that “the music lives on”.

He started his business empire in 1970 when he launched a mail-order record service. “Record retailing then was done alongside toothpaste and other boring products in Woolworths and WH Smith’s,” said Branson, reflecting on the landscape of the time.

“You’d have Frank Zappa alongside Andy Williams records, so there was no taste in the retailing at all. When we set up the first mail-order company, if you look at some of those full-page ads in the NME, they had character, they were risqué, and people related to them.

“It was obvious that the company knew its music and built the Virgin image as something very different to what was out there. People who liked to buy rock ’n’ roll would go to Virgin.”

Recommended

Two years later, a mail-order strike forced Virgin to find its own physical record store above a shoe shop on Oxford Street. “We put bean bags on the floor, people would be smoking joints and listening to the music,” Sir Richard remembered. “The success of that led to the Virgin Megastore on Tottenham Court Road, and that was the start of building around 350 around the world – from Times Square to Les Champs-Elysées and all the major cities.”

The journey only grew in legend from there: successfully campaigning for a number of countries to legalise selling records on a Sunday, before building its own recording studios – starting with The Manor in Oxford “where bands could record all night and sleep all day”, and later The Townhouse in London where Phil Collins recorded the iconic drum part to ‘In The Air Tonight’.

“I was actually in the studio at the time,” Branson recalled. “It sounded great, but I don’t know if it felt like history was happening. It might be the most famous drum solo of all time. That studio just had a wonderful sound.”

With a small recording studio empire built, Virgin soon found the need to launch a label.

“Mike Oldfield was staying at one of our studios as a 15-year-old lad,” Sir Richard told NME. “He worked with Tom Newman to make ‘Tubular Bells’. He played us the tape, we loved it, but we couldn’t find any record companies to release it. In the end we thought, ‘Screw this, we’ll set up our own record label and put this out’. Virgin Records as a label was born off the back of that.

“I brought John Peel to my houseboat, I played him the whole album. He loved it so much that he dedicated his whole show to playing the whole of ‘Tubular Bells’ that night. Off the back of that, it took off.”

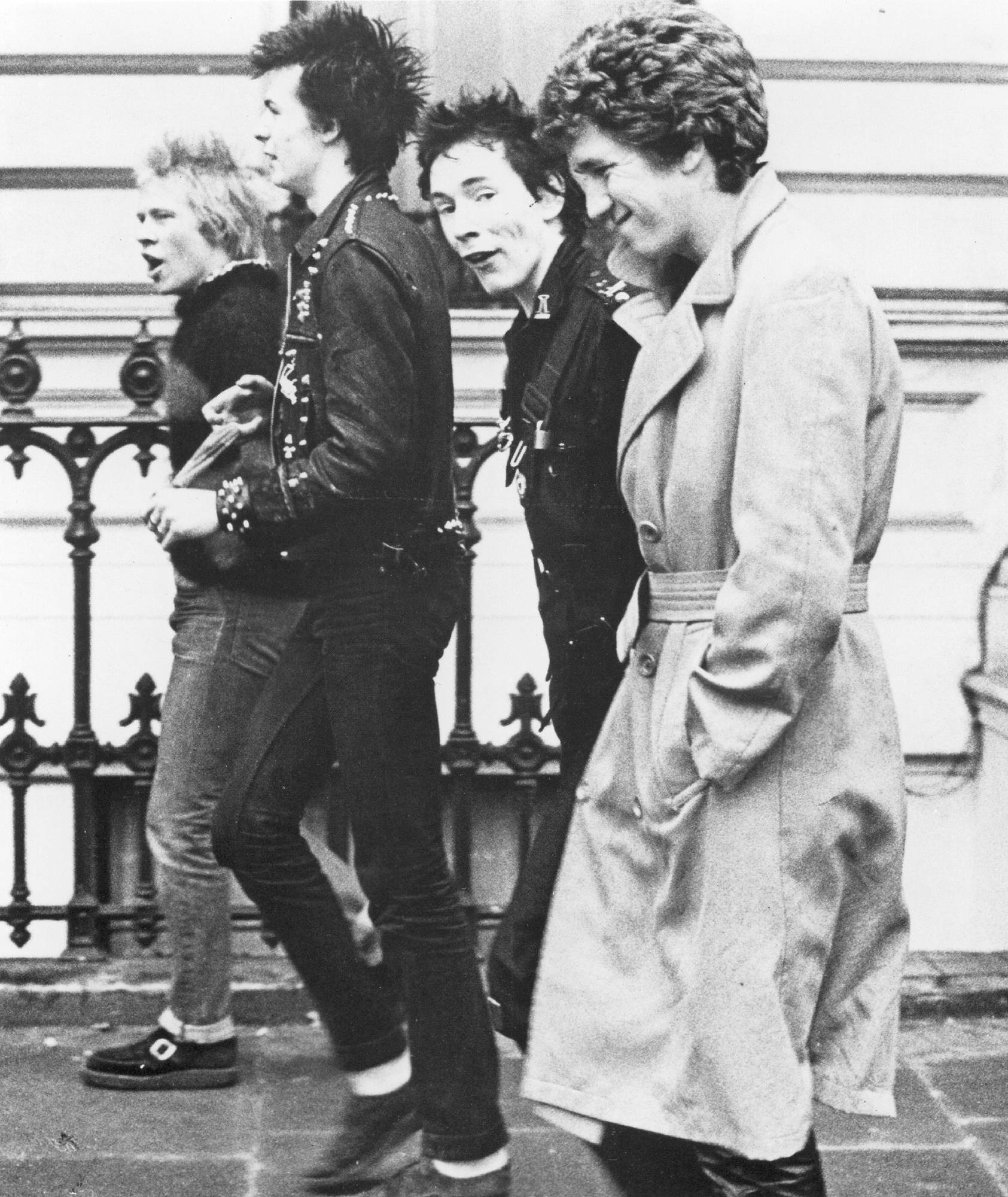

By the end of the ’70s, Virgin Records had changed the course of music history by giving Sex Pistols a home when no one else would – leading to the label later attracting the likes of Janet Jackson and The Rolling Stones. In the ’90s, alongside Branson’s other multimillion business empire, he relaunched with V2, becoming one of the world’s biggest independent labels.

Check out our full interview with Branson below, where he told us about censorship, doing things differently, and the state of today’s industry.

NME: Hello, Sir Richard. When you first launched Virgin as a record company, what were you looking to do differently from other labels?

Sir Richard Branson: “Most of the other labels were very stuffy. The fact that EMI dropped the Sex Pistols because of one swear word on television shows you the era we were living in. A&M, who were supposed to be less stuffy, dropped them the next day. The Sex Pistols really helped propel Virgin and ultimately helped us attract artists like The Rolling Stones, Genesis and Janet Jackson. A lot of massive artists wouldn’t have signed with us if we hadn’t shown our powers at being able to put music on the map. We wanted to build the most credible and successful record label in the world, and the team at Virgin achieved that.

“We started having enormous success with Human League, Simple Minds, Culture Club, David Bowie – a whole range of fantastic artists – and then that later invited Lenny Kravitz, Spice Girls.”

[embedded content]

It would have taken balls to sign the Pistols in that climate. What kind of pressure was put upon you?

“Enormous pressure was put on the BBC to stop ‘God Save The Queen’ getting to Number One, and there was no question that it was Number One, and they skewed the charts. We were prosecuted for the word ‘bollocks’. Just the title ‘Never Mind The Bollocks, Here’s The Sex Pistols’ caused outrage. We were at an age not much older than them, we were just having a lot of fun. The more the establishment attacked us, the more we enjoyed it.

“John Mortimer, the wonderful playwright and Queen’s Counsel, offered to defend us. He asked me to find a linguistics expert, so I found one at Nottingham University whose reaction was, ‘What a load of bollocks; it’s nothing to do with balls, it was a nickname given to priests in the 18th Century. Would you like me to come to court and say this? I happen to be a priest myself. Would you like me to wear my dog collar?’ About three-quarters of the way into the case, John Mortimer asked him to roll his collar down to reveal his dog collar. They reluctantly found us not guilty.

“I was hoping that Sex Pistols could stay together and go on to become the new Rolling Stones of their era, which I think could have been possible, but obviously they imploded. Sid died, Rotten and McLaren fell out big time. I went with Rotten to Jamaica after that, and he was giving me advice to sign reggae bands to our new label, Front Line.”

Many (but not John Lydon) have drawn parallels between Sex Pistols and Kneecap. How do you feel that we’re here nearly 50 years later with a moral panic and government pressure and censorship over a band?

“Embarrassingly, I haven’t followed it at all, but the more the government overreact, the more successful something is going to be. If they do genuinely feel something is wrong, then you’re just playing into the hands of anybody you overreact against. That certainly happened with Sex Pistols.”

There’s a real fight for survival for artists, venues and the culture at a grassroots level in the UK at the moment. What do you think can be done to breathe life back into it and nurture talent?

“That’s a good question. It is very, very difficult today – but the record industry as such seems to be making a lot of money. If you don’t look after your artists and you don’t pay them well, then the industry is going to suffer massively in the long term.

“The era we lived in was a particularly good one in that we had the balance: the bands all did well and made a decent living out of it, the labels did well, and it was an exciting time.”

What do you think about the grassroots levy for arena and stadium gigs?

“The levy idea sounds like a good one, but how you choose who to give it to will be a fun one.”

And Brexit has had a huge impact on artists’ ability to tour as well…

“With Brexit, we took a shotgun and shot ourselves in both feet. It was such a big mistake, sadly. Wherever I turn with young people, it makes you want to weep. They can’t live, work or play in Europe. We just closed the door.”

Having been such a large part of it, do you think the music industry can and will change for the better?

“If the industry are making ridiculous sums of money, then they should wake up. It’s been consolidated perhaps too much. Independent record labels were what really brought life to the industry. It brought a lot of creativity. If you’re a big company without much competition, then it’s difficult to get your team properly motivated.”

What would your advice be for someone looking to start a label today?

“Find somebody from the tech world who has made a ridiculous amount of money and loves music and get them to invest in your company. Have a lot of fun giving it a go, but knowing that the person who has invested can afford to lose it all. There are trillionaires out there who’d be worth tapping up.

“My whole philosophy on life is, ‘Screw it, just do it’. If you come across a great band, just try putting it out and giving it your best shot.”

Other winners honoured for “championing songwriters and composers, helping to build a stronger, fairer, and more inclusive music industry” included RAYE, Kae Tempest, Jon Platt, Kanya King CBE, Sir Chris Bryant MP, Catherine Manners and the late John Sweeney.

Earlier this year, the Ivors Academy celebrated when major labels revealed plans to support songwriters and composers via the payment of per diems and expenses for recording sessions.