What do you see when you hear the word “Chicago”? In the popular imagination, it’s probably the skyline, skyscrapers with antennas forking into the clouds. Zoom in and you might focus on heavy and wet food like salad-loaded hot dogs, oily Italian beef sandwiches, and deep dish pizza. Think back and you’ll conjure Michael Jordan with his tongue out, Harry Caray’s blocky bifocals, or maybe George Wendt saying “Da Bears.” But if you’re from Chicago, you know these chestnuts are how tourists and transplants claim their Windy City bona fides. Most Chicagoans don’t picture the Sears Tower and Wiener’s Circle when they think of home. They see the lake.

Open the jewel case of Common’s second album, Resurrection, and right there, printed in purple and blue onto the CD itself, is the sun rising over Lake Michigan. The image is an exceptional rendering of Resurrection’s tone, which breathes Chicago with a mixture of defiance, exuberance, and reflection. Across its 55 minutes, you can hear 22-year-old Lonnie Rashid Lynn’s whole world: puttering down Lake Shore Drive in a beat-up Toyota Celica, hanging out at the 31st Street beach, riding through parks on Schwinn bikes, making runs to the liquor store. It’s a portrait of a specific slice of Chicago—a young black man’s experiences on the South Side in the early 1990s—but it also conveys the perspective of any teenager who grew up in the city.

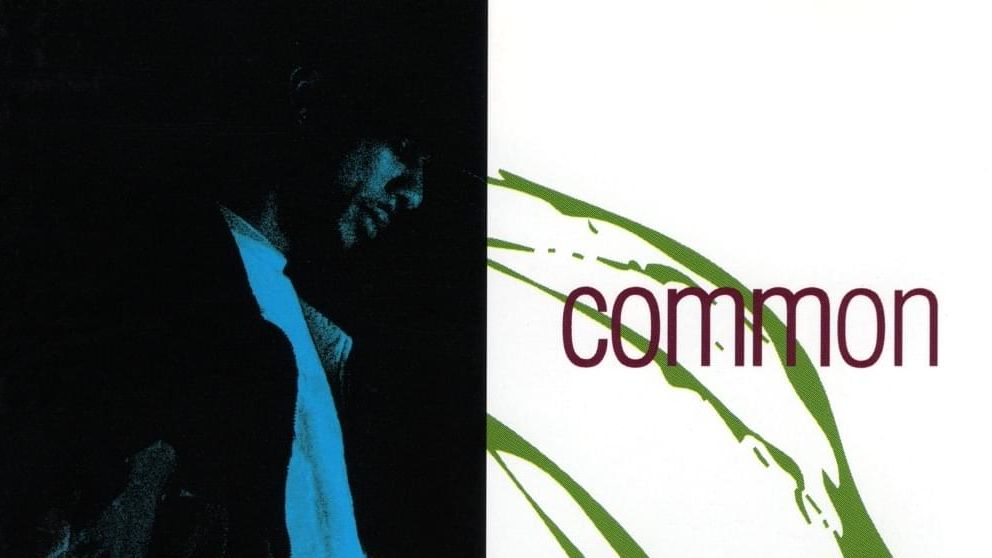

Resurrection brandishes its Chicagoness obliquely, through snapshots of everyday life, a cocky attitude, and richly expressive beats. But subtlety didn’t come naturally to Common, who at the time was going by Common Sense. The cover of his 1992 debut, Can I Borrow a Dollar? , is a photograph of him crouched down, wearing a White Sox skullcap and clutching a touristy Chicago coffee mug, with a map of the city overlaid on his crew assembled behind him — the visual equivalent of someone from suburban Tinley Park claiming to be from the South Loop.