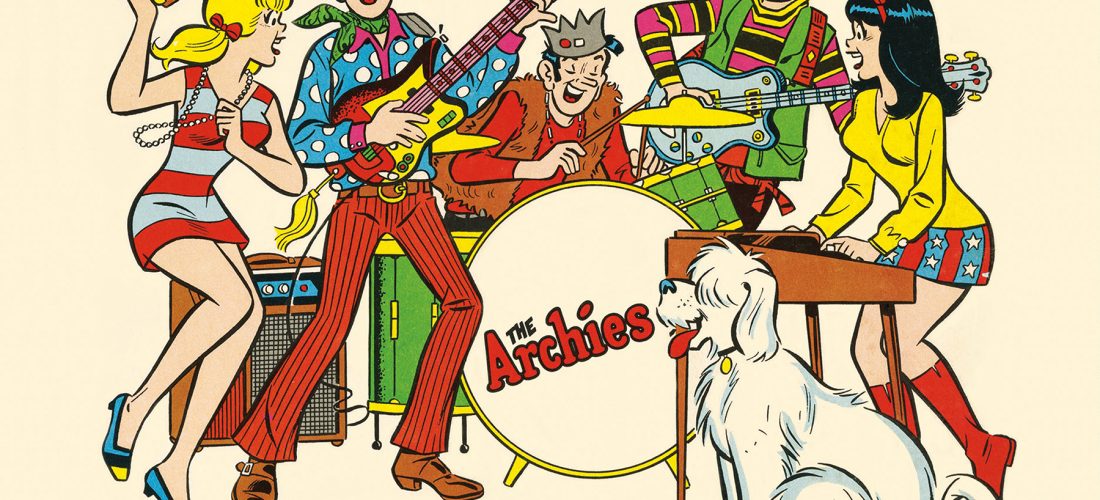

Remembering the Archies, a Fake Band Ahead of its Time

In an utterly accidental way, a box set devoted to the Archies, the infamous TV cartoon band of the Sixties, couldn’t have arrived at a timelier moment. Earlier this month, we lost the Monkees’ Michael Nesmith. The band’s musical gatekeeper, the one most preoccupied with the TV-generated combo being allowed to write its own songs and play on its own records, Nesmith famously rejected “Sugar, Sugar” — a bubblegum pop song as basic as it gets, brought to them by producer Don Kirshner.

As the late Kirshner told RS in 2009, Nesmith’s dismissing of the song inspired him to turn to animation: “Mike said, ‘It’s a piece of junk–I’m not doing it.’ I came home and my son Ricky was reading Archie comic books.” Inspired by that sight, Kirshner flashed on turning the comic into a cartoon series — and having Archie, Jughead, Veronica and the gang perform the songs, instead of actual three-dimensional humans with opinions. “And I created the Archies,” he said. “That’s all because the Monkees wouldn’t do my song and that got me pissed off.”

Kirshner knew a hit when he heard it: In 1969, “Sugar, Sugar” wound up knocking the Rolling Stones’ “Honky Tonk Women” out of the No. 1 spot, where it stayed for four weeks; it also became the biggest-selling hit of that year. The cartoon series, which launched in 1968, just as The Monkees was being cancelled, had its dopy charms. But of all the Sixties artifacts to survive and prosper five decades on, it’s doubtful that anyone, even Kirshner, would have predicted the Archies would make that list. The series is hardly remembered as a high watermark of animation, and neither are the five Archies albums —billed to the cartoon characters but sung and played by uncredited studio players — recalled as anything but forgettable cash-in product for a Saturday morning cartoon show.

And yet the Archies continue being reanimated. Riverdale, the self-consciously somber update of Archie, revived the Archies as a “band,” albeit as a predictably gloomier one playing dour pop like “Midnight Radio.” Last month, Netflix announced a “live action musical” film version of The Archies, to be directed by Zoya Akhtar and set in India. (And let’s not forget the way the Gorillas inherited the cartoon-band legacy decades later, or that Bored Ape Yacht Club, those cartoon monkeys that are the talk of the NFT world, are venturing into music.) In that context, the existence of Sugar, Sugar — The Complete Albums Collection (Goldenlane)– which boxes all five of the Archies LPs (minus their obligatory Christmas record) — makes some sort of crazy sense.

The naysayers of the time, like the emerging rock press that dismissed the Archies records as disposable junk, weren’t completely wrong. Throughout the five discs, there aren’t too many other tracks to rival the undeniable hook and “pour a little sugar on it” grit of “Sugar, Sugar.” (Even soul great Wilson Pickett covered it, albeit as a slow-jam groove.) But the box set also serves as an instruction manual on the glories and pitfalls of bubblegum pop, lessons we’re still seeing played out today.

The people behind the Archies — songwriter and producer Jeff Barry, singers Ron Dante and original female voice Toni Wine, renowned musicians like guitarist Hugh McCracken and bassist Chuck Rainey — knew what pre-teens of the time wanted — unadulterated silliness like the Ohio Express’ “Yummy Yummy Yummy.” The first two Archies albums, The Archies and Everything’s Archie, pretty much delivered on that promise. There’s a lowest common grade-school denominator to chipper bangers like the bouncy “Time to Love”; “Hot Dog,” an ode to food largely bereft of double entendres; and the “group”‘s first single, the head-over-heels “Bang-Shang-a-Lang,” which was reminiscent of early Barry-penned hits like the Crystals’ “Da Doo Ron Ron.”

But then you stumble across harder rock like “Truck Driver” (narrator tries to hitch a ride in order to find missing girlfriend) and the mildly naughty “Hide and Seek”–-which has such a funky guitar lick and backbeat that it was almost featured in The Get Down, Netflix’s sadly canceled series about the early days of hip hop. (A lawsuit put a halt to those plans.) “Seventeen Ain’t Young,” a slow-high-school-dance lament about love between teens, isn’t as smarmy as it sounds.

Starting with its title, “Sugar and Spice” — from their third album, 1969’s Jingle Jangle — wanted very much to be “Sugar, Sugar,” although it couldn’t replicate that song’s fizzy highs. Jingle Jangle is what one could call the Archies’ transitional third album, since they stomp a little bit harder (“Get on the Line”) and dip into Motown grooves (“She’s Putting Me Thru Changes”). You can hear the Archies — or at least the living humans behind them — aiming to grow as artists, even if novelties like “Senorita Rita” still hobble them.

Like many of their peers, animated or fleshy, team Archie wanted to be taken seriously. Sunshine, from 1970, strained to be as relevant as possible, which meant a dose of then-voguish eco-pop (“Mr. Factory,” in which “The little fish ain’t growin’ ’cause the dirty river ain’t flowin’/Doesn’t anybody want to see it clean?”). “Waldo P. Emerson Jones” name-drops rock festivals and FM-radio gods of the day: The title poser “took his chopper up to Woodstock/And he wormed his way backstage” and “says he knows the Beatles/S&G and Jimmy Page.” (Waldo is also putting the moves on the singer’s girlfriend, which doesn’t help his case.) The lyric of “Summer Prayer for Peace” mostly amounts to rattling off the population numbers of major cities and countries, including North Vietnam. In Sunshine, the seeds were planted for later, maturity-minded records like the Osmonds’ concept album about Mormonism (The Plan) and the Jonas Brothers’ somber-minded Lines, Vines and Trying Times. And as with Sunshine, those records were also hit-free as a result.

Sunshine peaked at a lowly no. 137 on the Billboard Top 200. Not surprisingly, their Archies’ farewell, 1971’s This Is Love, returned to bubblepop basics, only revealing a few nods at musical sophistication (the percussion, horns and funky bass on “What Goes On”). Their weakest set, it didn’t make the charts at all. By then, the Archies were old Saturday-morning news next to the ascendant Partridge Family (whose winsome harmonies, also courtesy studio players, echoed those of the Archies) as well as the Osmonds and the far superior, and meatier, Jackson 5.

With that, the Archies crashed and burned, at least until the recent revivals. But for so many pop acts to follow, they sent up a warning flare: Stick with what you know and mature at your own risk, even if you’re made of cartoon cels.