The most important life lesson that a teenage Craig Wedren ever received may have been something that his voice teacher loved to repeat: “Take your bel canto and make it a can-belto!” Wedren, fortunately, was a born belter. A precocious middle-class kid from the Cleveland suburbs, he knew he wanted to be a rock star as soon as he discovered KISS. He sponged up the music his mom played in the car—Elton John, the Doors, Carole King, the Bee Gees—and internalized every lick of it. That knowledge served him well as a young teen: Cover bands were a central feature of middle-school social life in early-’80s Cleveland, and Wedren had both the repertoire and the voice for them.

He honed his falsetto by imitating vocalists like Freddy Mercury, Ozzy Osbourne, and Journey’s Steve Perry—stars who embodied the notoriously high registers of ’70s and ’80s rock radio. Singing into the Shure 58 he’d received for his bar mitzvah, and sharpening his vibrato to cut through the midrange, he learned to make himself heard over his eighth-grade bandmate’s Marshall half stack. They called themselves the Immoral Minority and played at being new wavers—a video shot by Wedren’s childhood friend David Wain, future director of Wet Hot American Summer, captures the 13-year-old singer in all his budding New Romantic splendor—although in Cleveland at the time, there wasn’t really any difference between underground and commercial, cool and uncool. The Bee Gees and the Germs, Def Leppard and Dead Kennedys—they all swirled together in the local teens’ tape decks, their only common denominator the big adolescent feelings they were capable of summoning.

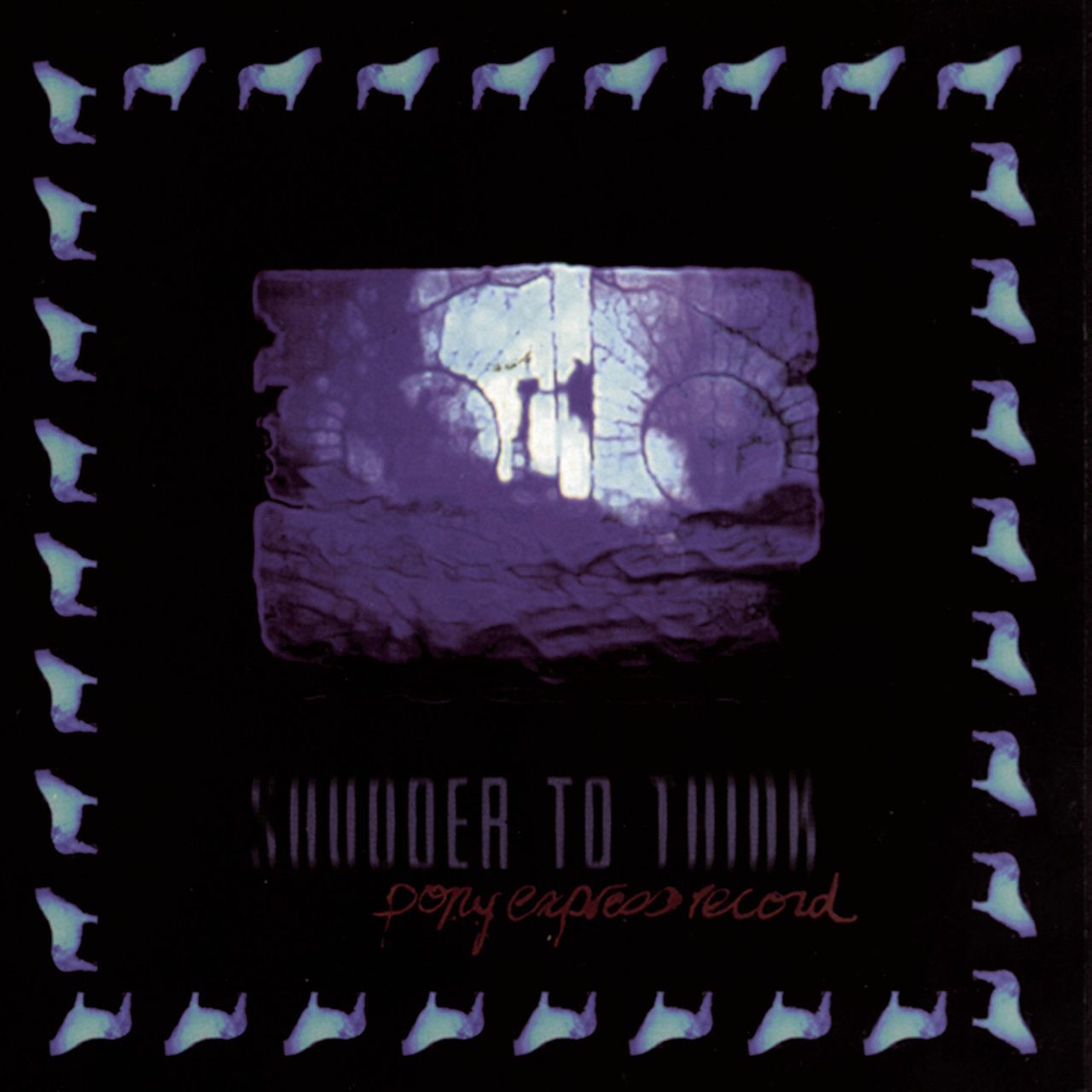

That spirit of openness, combined with his teacher’s technical advice, fatefully shaped young Wedren’s voice and vision, planting the seeds that would yield Shudder to Think, one of the strangest and most distinctive bands ever to emerge from the cauldron of American hardcore punk—creators of the 1994 album Pony Express Record, perhaps the unlikeliest masterpiece of the post-Nevermind major-label alt-rock signing frenzy.

In 1985, when 16-year-old Wedren moved to Washington, D.C. to live with his dad, kids from coast to coast were shaving their heads, shouting choruses, jumping off stages, and figuring out the bare minimum number of chords necessary for a 90-second juggernaut masquerading as a song. A loosely connected network of scenes was coalescing around the nascent American form called hardcore, and the nation’s capital was one of its major hubs, thanks to bands like Minor Threat, the Faith, Void, Government Issue, et al. At the center of the action was Dischord, the staunchly independent, fiercely idealistic record label helmed by Minor Threat’s Ian MacKaye.