The models are dressed for a 1990 music video shoot, but no one seems to have told them it’d be a Happy Mondays video shoot. To be fair, Happy Mondays appear to have no idea that they’re at a Happy Mondays video shoot either. At least a dozen women in tasteful cocktail dresses gyrate in an empty sound studio as Happy Mondays pantomime a song called “Kinky Afro,” wearing what looks like the clothes they slept in the night before.

That is, if they slept at all. The first look Shaun Ryder gives to the camera is so far beyond “hungover” that it’s uncanny, like a still from an I Think You Should Leave sketch 30 years ahead of its time. His fly also appears to be halfway down. The only guy in the band that’s playing in sync is Mark “Bez” Berry, the mascot/dancer/occasional percussionist whose main instrument is himself, except when he starts patting Ryder’s back like a bongo after a model steals his maracas. “Kinky Afro” is all quotables, but the most important line is, “What you get is just what you see.” And what you saw in this video is exactly what you got on Pills ‘n’ Thrills and Bellyaches—a Madchester masterpiece that could only come from the scene’s most functionally booted band.

“Kinky Afro” isn’t Happy Mondays’ biggest hit or defining song—that would be Pills’ rhymin’ and stealin’ lead single “Step On,” or the epochal Paul Oakenfold remix of “Wrote for Luck,” or “24 Hour Party People,” their sex, drugs, and on-the-dole anthem, and the namesake of an indispensable 2002 Factory Records magical realism biopic. After the tragic death of Ian Curtis at 23 ends the revolutionary post-punk phase of Factory, Happy Mondays appear in the film’s second act as unwitting insurgents, a signing that propels Factory founder Tony Wilson’s nightclub, the Haçienda, from a struggling warehouse venue to the locus of the ecstasy-fueled rave revolution that’s sweeping the UK. By the end of the movie, the Mondays are comic relief; with Factory in dire financial straits, they take a meeting with EMI, announce that they’re “going for a Kentucky [Fried Chicken]” when presented with a vegetable platter, and never come back. When we see them eating from an actual bucket of chicken, it’s a gag based on the open secret that “KFC” was the band’s code word for heroin.

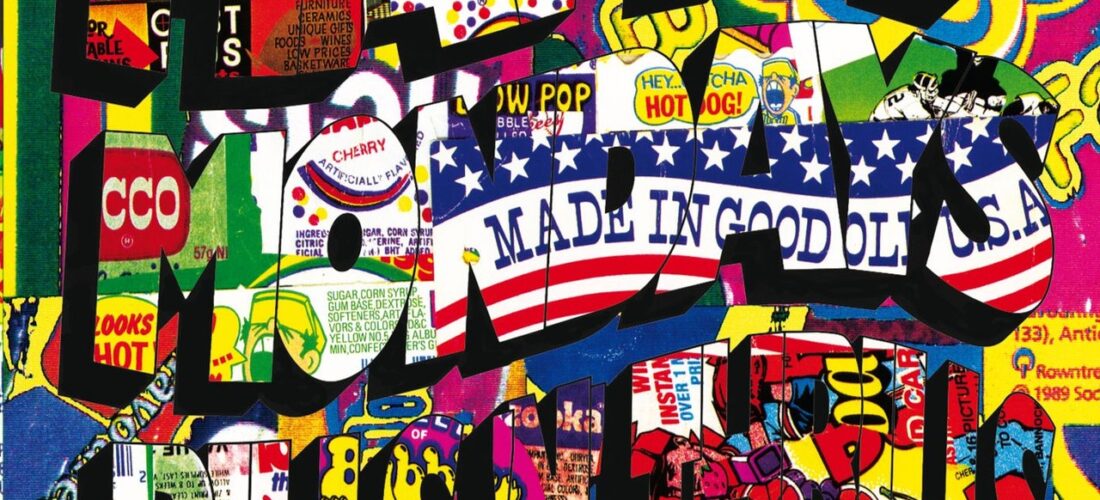

However, “Kinky Afro” remains Happy Mondays’ biggest hit in America. It’s central to the legacy of their third album, which was released on Elektra and recorded in Los Angeles because that was where these guys were less likely to get in trouble in 1990. Then again, maybe the famed Capitol Studios was just a proper compromise; if relative sobriety was truly a priority, the Mondays wouldn’t have also floated Amsterdam and Jamaica as options.