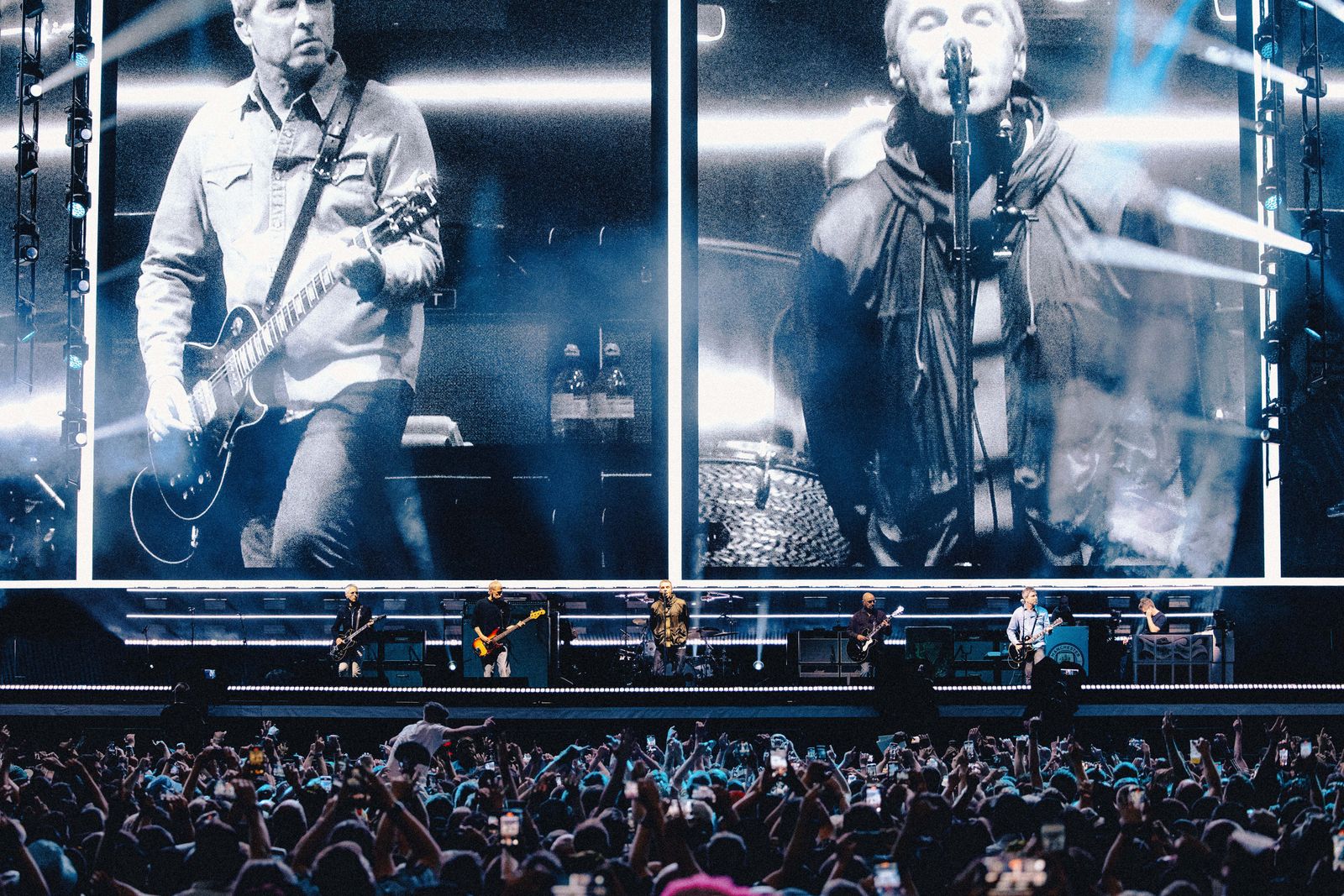

The first Oasis show in 16 years starts with “Hello,” amid scenes consistent with a riot. A continuous mosh pit thrashes through the center of Principality Stadium, from front to back and up into the stalls. Liam Gallagher is incandescent, his brow a triangular furrow; he yells at the mic as much as into it. “Hello, hello, it’s good to be back”—back in the 1990s.

By the end of the set, legion fans and critics—those there at the very beginning—will hail it as the best Oasis show since the mid-’90s. This is easy to believe. I was a bit too young for the first go-around, but witnessed firsthand the solo careers and the birth of the Oasis nostalgia complex. Tonight, the gravity of the occasion—perhaps the biggest reunion in our lifetime—makes the atmosphere combustible. Liam sounds ferociously on-form, his nasal snarl infused with a malevolent purr. Down the front, fans pogo, lurch, and squabble. A few get stretchered away, suffering an excess of ecstatic devotion.

Some 14 million people tried to buy tickets for the reunion tour, likely to be the most profitable in British history. One in 200 of them made it to Cardiff. As with Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour, host cities have transformed into themed boutiques. The London Dungeon will offer free eyebrow waxing in a “Gallagher Grooming Gauntlet.” A Manchester Aldi supermarket has been renamed “Aldeh,” honoring the Gallagher brogue. In Cardiff, a shopping mall has installed a 250-square-foot mural of Liam and Noel made entirely of bucket hats. Dozens of Oasis merch stalls clog the streets, with fans dressed in the old merch awaiting the new. Lines snake along the main strip and into side alleys where men in vintage tees bellow “Live Forever,” pints aloft.

Liam has fired up the tour with his usual zeal. He excoriated Edinburgh’s local government (“quite frankly your attitude fucking stinks”) when councillors fretted over the influx of “rowdy” middle-aged men. These visitors, documents warned, were liable to drink to “medium to high intoxication.” This may seem a generous assessment—a prudent forecast would be crazy-high intoxication, at a minimum—but this pertains to the have-it-large contingent, which is relatively small. Among viewers of the Cardiff bucket-hat mural, for instance, are children and teenagers escorted by parents whose own parents took them to their first Oasis shows.

Even the most sentimental fans are under no illusions about the reunion’s motive: Oasis are in it for the money. But the promise of exorbitant profit only compounds the pressure on opening night, where fans who paid up to $500 for face-value tickets (thanks to Ticketmaster’s contemptible “dynamic pricing” model) will find out how much Oasis still mean to them, and how much the reunion means to Oasis.

As “Hello” tumbles into beloved B-side “Acquiesce,” the energy is frenzied, the sound mammoth. It is hard to tell where the feedback stops and the rapturous screaming starts. The camera catches bassist Andy Bell grinning at Noel and wiggling his eyebrows, as if to say, “How about this then?”

The band exerts calm control. Barking through a thunderous suite of “Morning Glory,” “Some Might Say,” and “Cigarettes & Alcohol,” Liam stands sternly inert, silhouette frozen at the mic stand. Denim-shirted Noel seems a bit aloof, as if he might be an undercover operative from Edinburgh Council. But the tradeoff for theatrics or chemistry is a set so heavy, quick, and tightly drilled that it instantly obliterates its own memory, propelling us deeper into the past, without a moment to comprehend that any of this is really happening.

On the train to Cardiff earlier that day was an artist couple visiting Wales from Berlin, a toddler bobbing on the father’s knee. The mother asked whether we were excited for the show.

“I’d be interested to watch the audience,” she added. “I associate Oasis with….” Something hovered on her tongue.

“Lads?” her partner offered.

“Nationalism,” she whispered.

You may have noticed that Britain has a testy relationship with the Gallaghers. The symbolism of Oasis has been nuclear since at least 1995, when the music industry staged a proxy war between North and South by pitting Blur against Oasis. None were more readily equipped than these witty, working-class sons of Irish immigrants to capitalize on class animosity. When the music press successfully turned Britpop into an authentocracy, Oasis became champions of the world.

They had released two classic albums, Definitely Maybe and (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, in 1994 and ’95. Noel wrote the songs, mostly incendiary anthems and meaningless ballads about being overwhelmed by unexamined feelings. Liam bulldozed through it all in a tone that made the ballads sound like threats and the threats feel like fatwas. Together, they caused a sensation of rock fervor, mysterious male tears, and illicit hedonism. That certain corners of the media clutched pearls over songs like “Cigarettes & Alcohol” (“You might as well do the white line,” went a briefly infamous lyric) only served to rally Oasis fans against the out-of-touch elites telling them how to live their lives.

Cocaine was not the only white line Oasis worshipped. The Gallagher songbook, critics noted, descends from the palest lineage of rock patrimony, from the Beatles to the Stones to the Who to the Kinks to the Pistols to the Stone Roses. Without the funk and rave drive of their Madchester forebears, the band’s meat-and-potatoes rock’n’roll embodied a quintessential and incurious concept of English identity.

Liam and Noel were not foolish enough to be defensive about this, and their lack of given fucks made them only more beloved. Oasis were an everyman band but virtuoso interviewees. Asked about their rejection of dance influences in a 1994 interview, Liam said, “Sly Stone is good music, right. But all this dance music these days is all that same silly beat going DANK DANK DANK and some guy singing ‘we’re all free’ when you’re not. It’s shit.”

This is not so far from assessments within the dance underground itself. Where electronic producers responded with darker sounds and post-rave exegeses, Oasis sought to reawaken rave’s collective euphoria with carnivals of individualism. Concerts like their record-breaking run at Knebworth, in 1996, could not be mistaken for “we’re all free” communion. The Gallaghers’ goal was a total monopoly.

As world domination beckoned, a cult of authenticity surrounded them. But the reality of the Gallaghers’ worldview—including many instances of offhand homophobia—came to represent, to critics like the late Neil Kulkarni, “the homophobes and racists taking over, the rejection of queerness stylistically, and the reassertion of the English Rock Defence League’s tiny-minded ideas about ‘proper music.’”

It is possible to sympathize with this wide-angle view (and to loathe Noel’s political beliefs) while finding, at a 30-year remove, plenty to cherish in the Oasis catalog. In any case, by the turn of the millennium, the band had been fossilized by its own success. In their final, stagnant decade, there was no overlooked classic, no leftfield gem, no devoted South American nation that held the new stuff in surprisingly high regard. There was only a descendancy of imitators, high on the Gallaghers’ inexhaustible supply of rock’n’roll moxie.

The band’s split, in 2009, resulted from a bust-up at Paris festival Rock en Seine. Liam had swung a guitar at Noel’s face after allegedly—and you have to picture this part—angrily throwing a plum at the dressing-room wall. The reunion has been portrayed as a shameful indulgence, marketed to men who built their music taste around a fear of looking silly. But what could be sillier than throwing a plum? Or jumping up and down while your friends chatter away, because this one is your song, your little oasis of individuality?

In a quiet moment after “Roll With It,” Noel hurriedly mutters something into the mic—a joke, I think, about Ticketmaster’s dynamic pricing fiasco. It dawns on me that his demeanor has nothing to do with indifference or hostility. For the first time, he looks nervous. Liam vanishes and Noel plays a suite of his own, starting with “Talk Tonight.” It would be an exaggeration to say a hush falls upon the stadium, but warmth and goodwill emanate from the crowd. This is evidently a bigger deal for studious Noel—ever the reunion holdout—than his shenanigan-loving brother.

He gives the floor to the crowd to conclude “Half the World Away” in almighty unison. “Little by Little,” the only song on the setlist recorded after Oasis’ 1990s heyday, is a marvel: Backed by 100,000 lungs, it transforms into a prog-rock torch song with jet-engine lead guitar and slashes of astral soloing.

Liam reappears with maracas for “D’You Know What I Mean?,” “Stand by Me,” and “Cast No Shadow,” a plodding suite that threatens to briefly lose the crowd. At least, it would, were the crowd not already committed to turning every scrap of recognizable melody into a soul-rousing terrace chant. It ought to be a problem that Oasis’ medium-pace songs just sound like their fast ones done slowly. It ought to be a problem that all such songs fall in the baggy second half of the main set. It ought to be a problem when Liam asks if it is worth “the £40,000 you paid for the ticket” and takes it upon himself to answer: “Yeahhhh.” And these things are problems. But inside the stadium, problems do not seem to matter.

“Slide Away” is a black-magic powerhouse full of melodic origami. “Whatever,” never featured on an album, is recited word-for-word by a bowl-cut boy in the crowd no older than Dig Out Your Soul. And suddenly there is “Live Forever”—a song so alive with possibility, so burnished with yearning melancholy, that its shallow sentiments fill your heart to the brim, even if Liam has more passion than breath in his lungs. “This is our last one, ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Star,’” he tells us (nobody believes this), and once more he sounds amazing, spinning off-piste, riffing and ad-libbing, showing us the hiding places in a song he has lived inside for 30 years. They play the finale as an incendiary waltz, guitar squeals tumbling into a furnace of feedback, as Joey Waronker’s hired guns pound the drums for dear life.

Noel returns for the encore and introduces the band, including “uber fucking legend” Paul “Bonehead” Arthurs, but not Liam, who sits out as Noel eases into “The Masterplan.” During “Don’t Look Back in Anger,” yellow bees adorn the screen, the symbol of the 2017 Manchester concert bombing, to which the song became an impromptu elegy. Many of Noel’s best ballads thrive on being romantically inarticulate, but attach them to a tragedy and they are ripe for emotional demolition. I have the strangest thought: I wish Liam was on stage to see this.

When he does return, for “Wonderwall,” everyone sings along, knowing exactly as much and as little as it means. Of course Liam takes this peak of intensity to sneak in a gag: “There are many things that I would like to say to you—but I don’t speak Welsh.” This, after all, is what Oasis stand for: Take life by the horns; throw in some jokes; and never overthink it. If either Gallagher could fluently express his emotions, Oasis would not enchant us, particularly the similarly afflicted, in quite the same way. “Champagne Supernova,” a final, masterful nonsense, closes the show with an infernal sigh. After barely acknowledging each other all evening, Liam pats his brother on the back—a gesture portrayed on social media, generously, as a conciliatory fraternal hug—earning a last whelp of joy from the exhausted crowd.

As people pour out into the Cardiff night—a vibrant economy of sweaty revellers, units shifting from bar to bar—a teenage girl behind us cries her eyes out, not saying why but accepting a tissue. Teens scooch to the exit while their parents glance back at an empty stage. And what of the rowdy middle-aged men? Many stare into the distance, grinning, stricken, or downing pints of alcopops; some edit videos on their phone, for Facebook or Instagram; I spot one giving another’s bum a cheeky squeeze. All of this is Oasis. A person who truly comprehends this band—who unravels the taboo, the glory, and the folly all at once—will know more about Britain than it knows about itself.

A final point of order on the crowd: Nearly all of the supposed delinquents and slobs who frequented the urinals during “Half the World Away” washed their hands upon their exit. One guy even rushed back to do so after getting called out by a friend. So take that, Edinburgh Council. Underestimate Oasis at your peril.