In 1973, the readers of Creem magazine voted New York Dolls the year’s Best New Band. They also voted them the year’s Worst New Band. The poll succinctly captured the polarizing effect of the group’s brief but marked reign over the Lower Manhattan rock scene, a post-Warhol Factory crowd that flocked to gritty gigs at Max’s Kansas City and the Mercer Arts Center. That year, the proto-punk enfants terribles released their self-titled debut and split their niche fanbase into even slimmer factions. There were those who loved the record—including veteran rock critics and Dolls devotees like Robert Christgau and Ellen Willis—and those who felt that the studio environment had sapped their live set and diluted their potent slurry of blues, early rock’n’roll, and girl group melodies.

And then there were the folks who just didn’t like the Dolls to begin with. The press in Memphis clocked their rouged cheeks and platform boots and wrote them off as “faggots.” Beer-swillers in Boston left in droves, marooning the band onstage in the 5,000-capacity Boston Armory. Years after the Dolls’ 1975 falling-out, charismatic frontman David Johansen explained the band’s highly “colloquial” sense of humor, which didn’t translate beyond “St. Mark’s and 2nd.” But punk entrepreneur Malcolm McLaren, who briefly managed the Dolls in their decline, might have summed up the group’s trainwreck charm best in a 2004 op-ed: “They were so, so bad they were brilliant.”

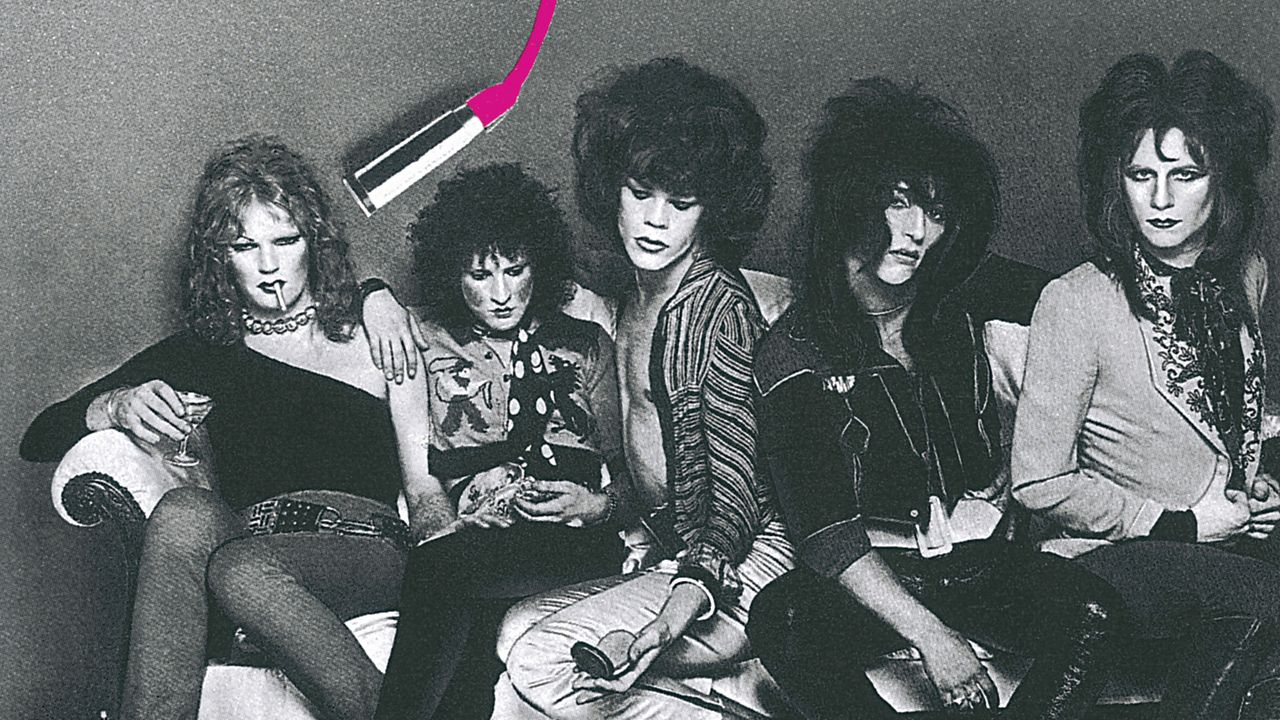

Before they were New York Dolls, the bandmates were outer-borough rogues who joined forces like the various mobs stalking pavement in The Warriors. Queens-born guitarist Johnny Thunders was a high school baseball player who, according to him, was scouted by the Dodgers. But when the pro team demanded he lob off his nest of jagged jet hair, Thunders refused. He dabbled in delinquency, roaming the streets with a petty gang called the 90th Street Fast Boys. Ill-starred drummer Billy Murcia was a Bogotà-to-Queens transplant and Thunders’ classmate. Bassist Arthur “Killer” Kane, a soft-spoken Bronx native who towered over his bandmates, was recruited in part for his imposing look (like a “mutated Marlene Deitrich,” as one critic put it). Sylvain Sylvain, a Queens boy by way of Cairo, replaced the group’s earlier guitarist Rick Rivets, who was booted for fucking off and showing up late to practice.

Johansen, the sole member from Staten Island, was born to a librarian mother and an opera singer-turned-insurance-salesman father. Despite this middle-class milieu, he was a puckish kid, taunting the nuns at his Catholic school, engaging in minor turf warfare by riding his bike into territorial neighborhoods, and sneaking spins of his older brother’s blues and doo-wop singles; the Diablos, Howlin’ Wolf, and Lightnin’ Hopkins were in heavy rotation. By age 17, Johansen had relocated to the East Village and was splitting his time between working at an outré clothing store on St. Mark’s Place and running the sound and lights at Charles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company, an outpost of camp, avant-garde drama that often cast amateur actors in gender-swapped roles. The experience might have influenced Johansen’s streetwalker chic, but by his account, the Dolls were cross-dressing long before they considered forming a band.