When David Lynch died this January, my life became filled, even more than usual, with short-form videos. These were clips from his movies and TV shows, the little weather reports he self-recorded in his final years, that wonderful footage of Angelo Badalamenti demonstrating how he and Lynch composed Laura Palmer’s theme from Twin Peaks. There were also pieces of Lynch’s interviews, usually circumspect and deliberately opaque. But one montage punctured that air of inscrutability: a cut of the director saying, over and over through the years, that failing to write down an idea and then forgetting it was one of life’s great horrors. He almost always punctuated this thought with the same sentence: “You want to commit suicide.”

About halfway through Neighborhood Gods Unlimited, Open Mike Eagle experiences a version of this: “I dropped my cellphone and it got ran over,” he raps, with the mournfulness of someone recounting a dying friend’s last days. “Didn’t even see it, now it’s in a bunch of pieces.” He croons about the “priceless data written on my machine” and says that his lost voice memos could have been the skeletons for “like eight or nine songs.” At one point he compares the infamous floods that destroyed hundreds of beats in RZA’s basement—then hedges, self-conscious. “I should’ve put it in the cloud,” he concedes. The song is called “ok but I’m the phone screen.”

Over the last decade, Eagle—a Chicago native who moved to Los Angeles and became a key part of the legendary avant-garde collective Project Blowed’s second generation—has emerged as one of the most incisive chroniclers of the ways the internet has fractured our existence. On the opening song from 2014’s Dark Comedy, he was dismayed that the banal details of his life and habits as a consumer would be valuable to anyone; a few tracks later he was rapping, tongue firmly in cheek, about the new “golden age,” where synthetic opiates are as readily available as “bad spoken word”—and where you can stream Twin Peaks on an iPhone, all that interdimensional dread shrunk down and made to lag and buffer. At one point in “phone screen,” he compares the experience of losing his notes and voice memos to an image that could’ve come right out of that show: a man “scratched up, trying to climb walls in a dream.”

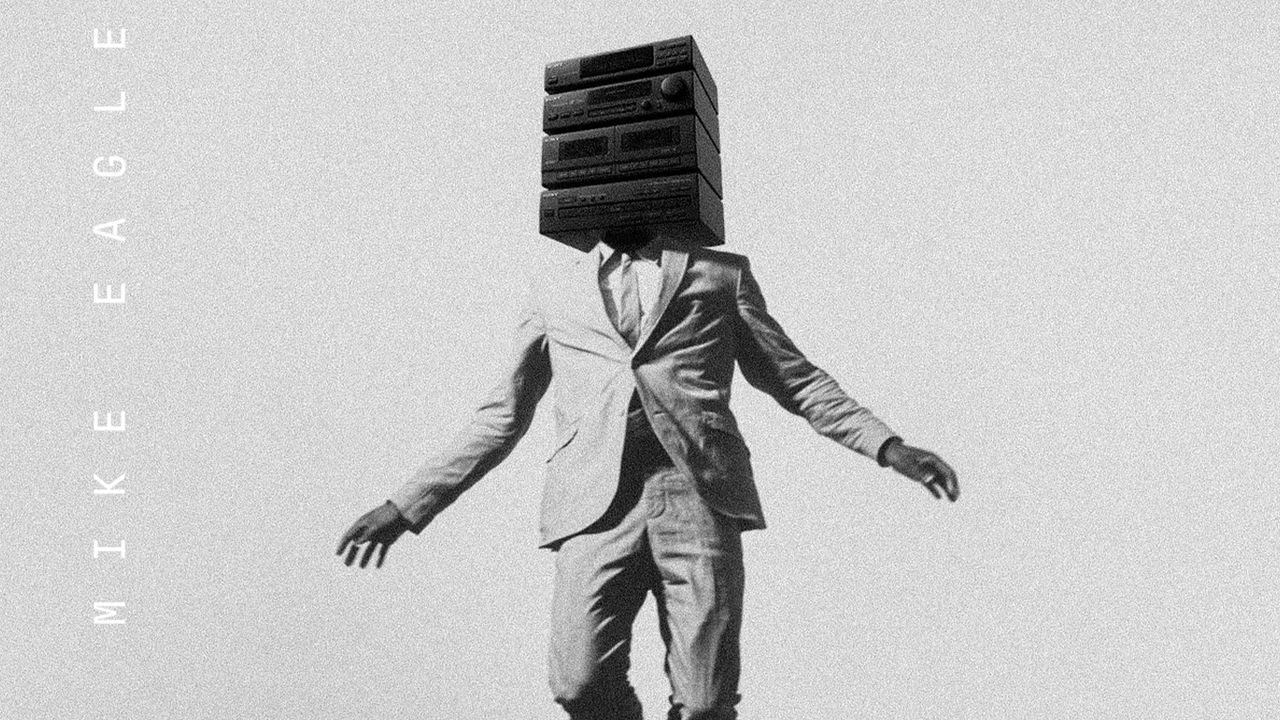

Neighborhood Gods is conceived as a dispatch from a fictional cable channel with a budget so small that it can only broadcast for one hour a week. And it does convey the texture of that medium, full of ads for wonder drugs and the harebrained barbershop theories from opener “woke up knowing everything”: chemtrails, freemasons, Gatorade laced with mercury. But the album’s spirit is unmistakably, claustrophobically online. It’s fixated on the ways parts of us are being stripped away and sold back for a price, be it literal or psychic; on “michigan j. wonder,” he raps about being his “own Dr. Frankenstein,” stitching together parts of his spine and flesh that had gone missing. It’s a disorienting way to live, and its roots stretch back decades, even centuries. But at his most determined moments, Eagle outlines a plan to claw back a comprehensive sense of self. Later on “michigan,” he repurposes an old line about “by-myself meetings,” first rapped by Cappadonna on Ghostface’s Ironman, a masterpiece made in the wake of those floods, when little bits of the artists had seemingly been lost forever.