Every couple of years I return to my favorite video on YouTube: a seven-minute clip of the rapper then known as Mos Def holding court in a studio, eliciting gasps and laughter from an unseen audience by reciting MF DOOM lyrics. This is all a capella; sometimes he adopts DOOM’s meter to emphasize its fine-watch precision, but more often, Mos breaks the spell and draws out the ends of lines as if he’s in utter disbelief: “Read the signs: ‘No Feeding the Baboons’???” he says, incredulously. “Seeing as how they got ya back bleeding from the stab wounds???”

Toward the end of the video, Mos raps part of Madvillainy’s “Meat Grinder.” That full-length collaboration with Madlib—one of the most anticipated, aggressively bootlegged, and ultimately acclaimed underground rap records of its time—vaulted DOOM to a new level of notoriety even as it threatened to overshadow everything that would follow. But for the most part, the verses that captivate Mos are from MM..FOOD, the 2004 album that punctuated one of the great madcap runs in rap history. At another point, someone from offscreen suggests that rapping alongside DOOM would be a challenge. The famously virtuosic MC shakes his head. “It would be fun,” Mos says. “He rhymes as weird as I feel.”

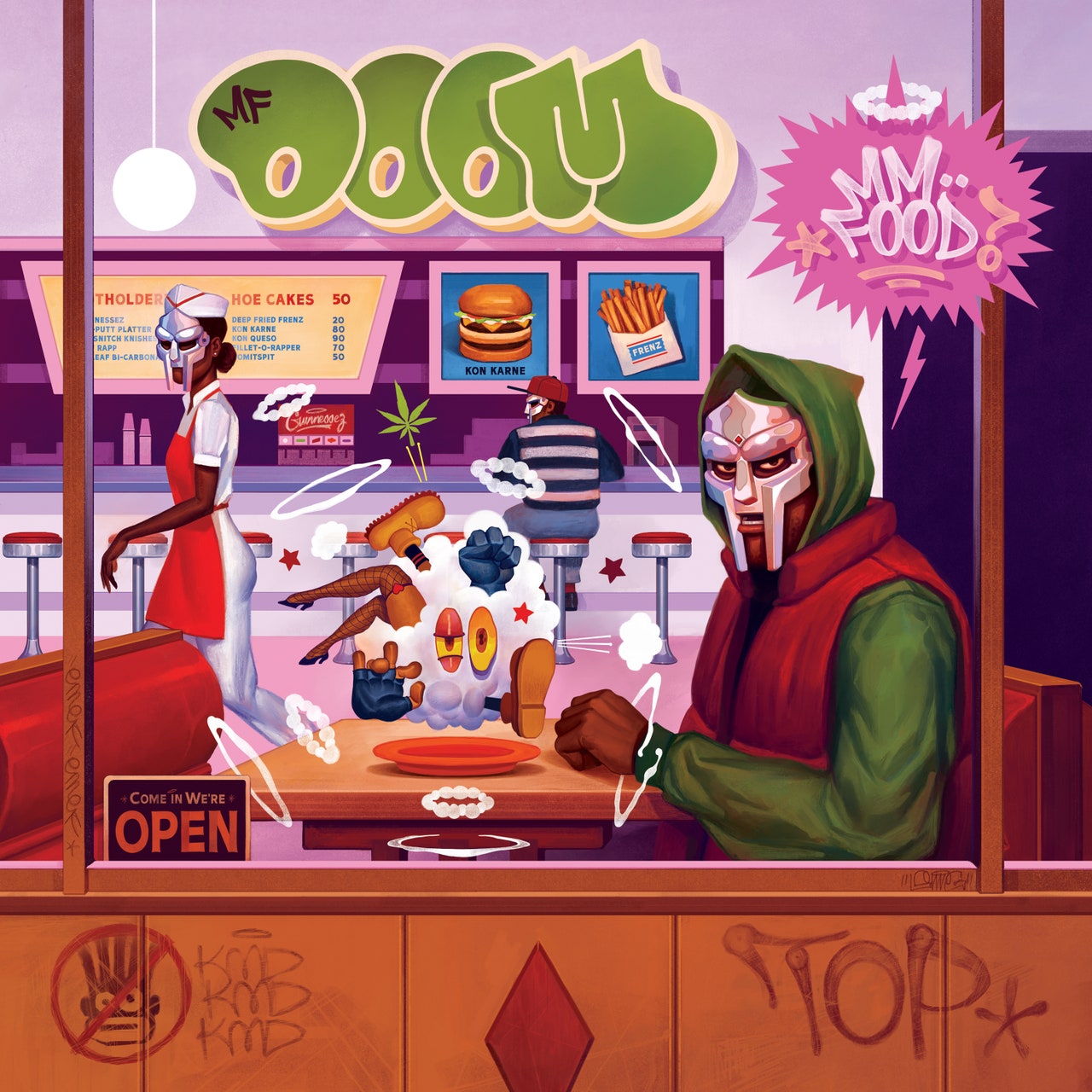

What is most striking about MM..FOOD—which Rhymesayers has reissued in a 20th-anniversary edition that includes a handful of remixes and brief clips from a previously unheard interview—is the way DOOM blends his absurd character sketches with real autobiography, his outre zaniness with something grimily naturalistic. Though nearly rendered a footnote at the time by Madvillainy, FOOD captures DOOM at his funniest and most mercenary. For a record that seems determined, at every turn, to lower the stakes—the culinary motif, the bizarre structure that leaves the middle of the tracklist completely bereft of vocals—FOOD stands alongside 1999’s titanic Operation: Doomsday as the most fully realized creation of rap’s greatest eccentric.

That mercenary bent is clear both in and outside of the text. At a glance, a few of the specs would suggest a tossed-off side project or the begrudging fulfillment of contractual obligation: the aforementioned suite of instrumentals, the apparent crowbarring into a release schedule. When he raps that he “plots shows like robberies/In and out, one, two, three—no bodies, please,’’ the second bar sounds an awful lot like “nobody’s pleased,” which would be a fitting reaction to DOOM’s well-documented practice of sending doppelgangers to lip sync and collect fees from club owners. That this couplet is rapped on a song cut from Madvillainy would only seem to confirm FOOD as a minor work.