“I still struggle to really describe what it felt like,” Neil Gust recently told Fucked Up’s Damian Abraham. He was talking about the wrenching feeling of discovering that his best friend and Heatmiser bandmate, Elliott Smith, was about to become famous on his own, without him. The revelation happened during the recording sessions of Mic City Sons, the band’s final album and their first since signing their big major-label deal with Virgin.

No one savored the milestone, despite having worked ceaselessly toward it for years. Bewilderment, mute hurt, and resentment reigned. Thirty years on, all the surviving members of the band—singer-songwriter and guitarist Neil Gust, drummer-producer Tony Lash, and bassist and organist Sam Coomes—still talk about the Mic City Sons sessions as if piecing together a relationship-ending fight that happened in the middle of the night.

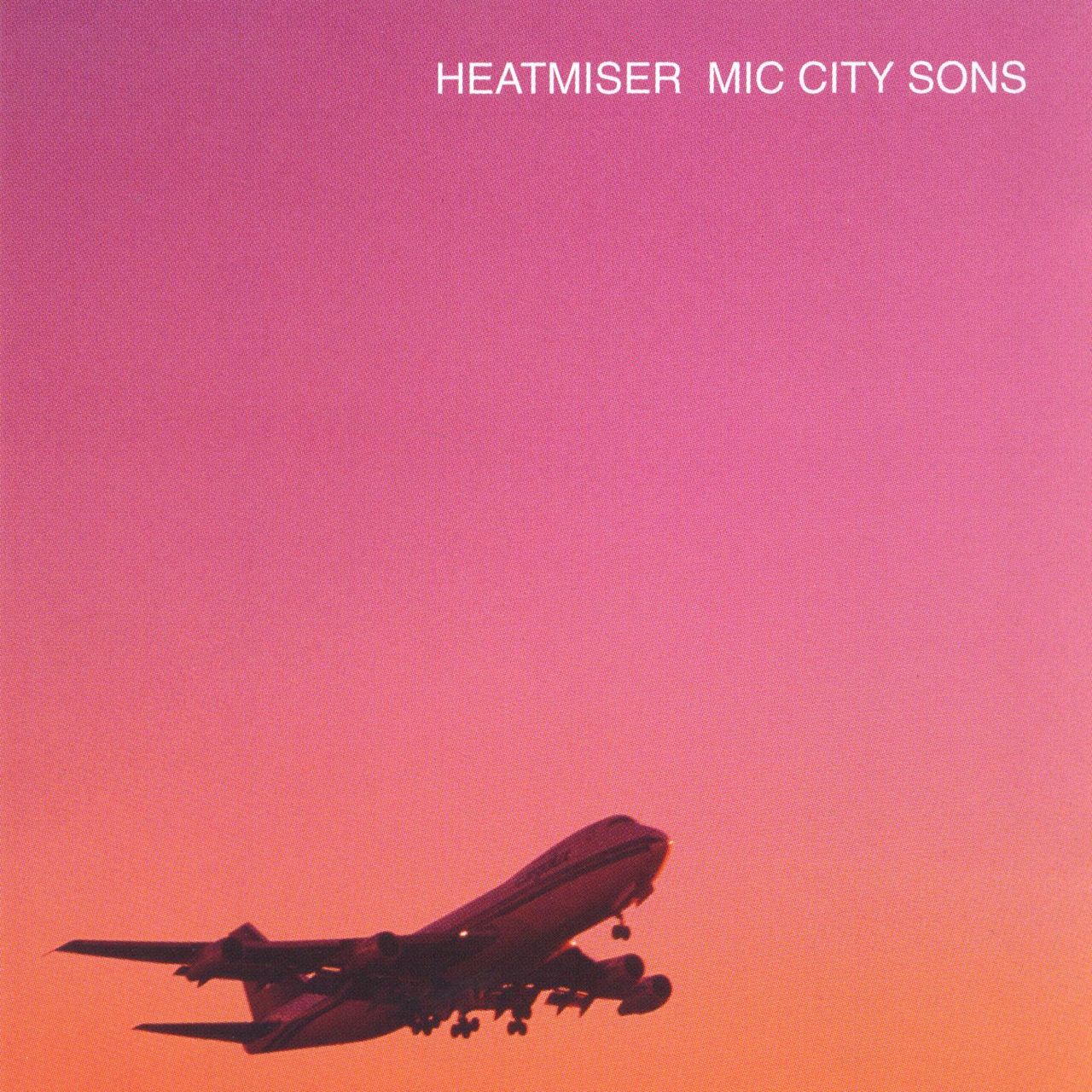

For most people, the Heatmiser story is Elliott Smith prologue, the group of friends he had to leave behind to embrace his solo career. Mic City Sons, their best album, is often painted as the moment when he began to transcend the band, when his staggering gifts started to break their containments. But for the men in the room with Smith, the story was a lot more wrenching and confusing. For them, Heatmiser was a story about how their beginning became their end, how far they’d come to get to this point, and their struggle to hold onto their friend.

Heatmiser were meant to be loud. Gust and Smith bonded over distortion blasts: They thrilled to a mindblowing Fugazi show, nursed keen disappointment at a lackluster Jane’s Addiction gig. They both bought Marshall half-stacks the same summer that Nevermind came out, and Heatmiser was forged in the fires of sweaty punk clubs like La Luna. They were muscular, confrontational. In these early years, Gust’s voice was the more self-assured one: He sounded more commanding while sneering over feedback-drenched guitars than Smith, whose little voice often trembled when he pushed it.

But when the feedback died down, Smith’s teenaged devotion to prog-rock epics began to subtly make itself known in his songwriting, particularly in his use of passing chords—chords with pieces and hints of other chords, shadows and implications of places where the song had not yet gone. Unlike the Beatles, who used passing chords as elegant stairsteps to blooming major-key choruses, Smith’s songs lived in the spaces between. “Plainclothes Man” is a profusion of chords—blue ones, inquiring ones, sour-apple ones, chords like a grimace and and chords like a pained laugh. There is no bright chorus waiting on the other end of them, just an endless fog of mixed emotions. Heatmiser’s music came alive in this conversational midrange, somewhere between a wry laugh and mutter.