Lookout! founder Larry Livermore on 12 shows that changed his life, from Woodstock to The Weakerthans

Lookout! Records is still technically no more, but the label has “reunited” for a livestream series called ‘LOOKOUT ZOOMOUT,’ which continues with episode 2 on Sunday (2/28) at 3 PM ET (noon PT). The lineup features a “rare solo performance” from Dan Vapid (of Screeching Weasel, Riverdales, etc), Dr. Frank from The Mr. T Experience, Go Sailor’s Rose Melberg, Kepi Ghoulie, The Smugglers’ Grant Lawrence, and Lookout founder (and How To Ru(i)n A Record Label: The Story of Lookout Record author) Larry Livermore.

Tickets for episode 2 are on sale now, and to get an idea of what to expect, we’re premiering a highlights reel of the first episode that you can watch right here:

We also caught up with Larry Livermore over email, and he made his a list of 12 shows that changed his life. His eclectic list includes everything from The Supremes to the MC5 to the original Woodstock festival to The Go-Go’s to the Ramones to Operation Ivy to Sweet Children (who later changed their name to Green Day) to The Weakerthans to Lookout’s reunion festival The Lookouting, and more. He had plenty of awesome stuff to say about each show (at least some of which he also mentions in his book). Take it away, Larry…

12 SHOWS THAT CHANGED MY LIFE (by Larry Livermore)

Music journalism is replete with terms like “epic” and “life-changing,” so much that you’d think every human being within reach of a bar, club, arena, or stadium would have had his or her life transformed several times over by now.

From the quantum metaphysical standpoint, where a flap of a butterfly’s wings affects the whole universe, it would be impossible to attend any show – unless maybe stayed comatose the whole time – without being somewhat altered.

But there are those that stand out. Looking back on more than half a century’s worth of gigs – from Pavarotti to the Sex Pistols, Segovia to the Clash, Rubinstein to the Rubinoos – I realize there are certain ones that played a vital role in shaping who and what I would become. Without them, it’s unlikely Lookout Records – or anything else I’m known for – would have ever existed.

1. Summer, 1965: The Supremes at the Michigan State Fair.

I’ve never made it a secret that my first inspiration for both a record label and a music scene was Motown. It brightened my teenage years immensely, and injected, as Marvin Gaye would have said, pride and joy into the citizenry of a town previously known mainly for cars and pollution. Seeing the Supremes, three girls from the projects who had just racked up a string of Number One hits, was amazing in itself, but equally astounding was the unprecedented sight of thousands of Detroiters, Black, white, and everything in between, dancing and singing along together. It was the first time I realized you didn’t need to wait for the big shots from New York or Hollywood to come make you a star. You could Do It Yourself.

2. Summer, 1965: The MC5, on a tennis court, Allen Park, Michigan.

I really can’t remember which I saw first, the Supremes or the MC5. The two shows kind of blur together, and had a similar impact on me, even though one was massive and the other involved a couple dozen kids in a treeless park on a baking-hot afternoon. Garage bands, pseudo-mod rockers, and soul-fusion outfits were springing up all over Detroit, but in our Downriver neighborhood, the big rivalry was between the Satellites and the MC5. This was supposed to be a battle of the bands to settle the issue, but though the MC5 were clearly onto something beyond what any of us had seen before, the Satellites had home court advantage (the MC5 were from neighboring Lincoln Park), and were awarded the prize. But as with the Supremes, the MC5 showed me how stars were created, and how the most vital part of that work was up to you.

3. May 5, 1968: The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead, Central Park Bandstand, New York City.

By 1968, owing to some misunderstandings with the authorities, I was living “underground,” as was all the rage that year. One of my hideouts was in an abandoned building on the Lower East Side, and to save the cost of a 20-cent subway token, I walked all the way uptown to see the free concert everyone was talking about. I wasn’t a Butterfield Blues fan, but the afternoon was amazing enough that I acknowledged them as “all right.” I was a huge fan of the Jefferson Airplane, and they lived up to my expectations. But the big surprise was the Grateful Dead, who I was officially neutral on. It wasn’t the band’s performance, excellent as it was, that made the biggest impression on me. Rather, it was the fans, who, long after the Dead left the stage, kept pounding out the rhythm on garbage cans and park benches and carried on dancing in a synchronized choreography worthy of a Busby Berkeley spectacular. Some sort of spirit had entered into thousands of them, inspiring them to move and act as one. From then on, I expected and demanded nothing less of my music.

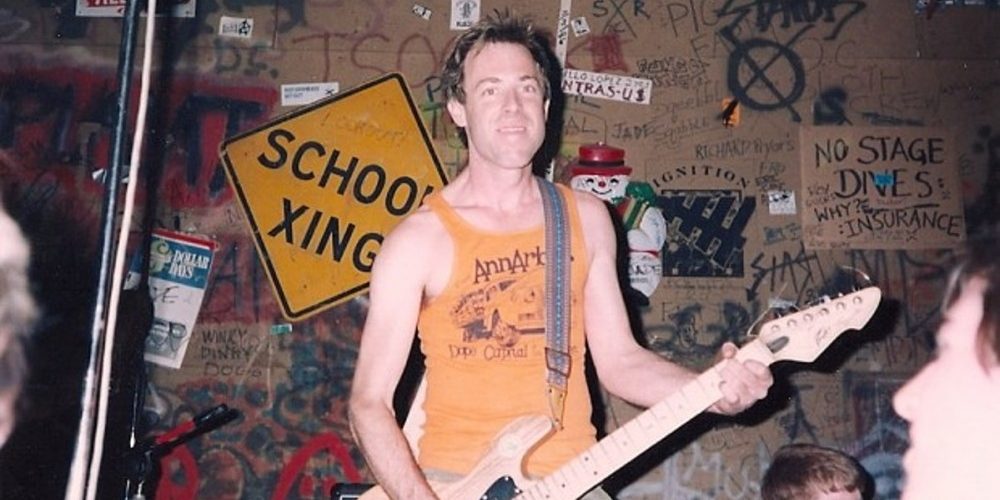

4. August 1-3, 1969, Ann Arbor Blues Festival, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Without resorting to Google, I’d be hard pressed to name half the blues legends I saw for the first time, among them Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Big Mama Thornton. But my most transcendent moment came when B.B. King, who was just beginning to break through to the mainstream, announced at the end of his set that he wasn’t anywhere near ready to quit playing, so he, his band, and a few hundred fans adjourned to a lecture hall on the University of Michigan campus where he carried on until dawn. It was totally free; he didn’t make a dime; he was playing for the sheer joy of it. Wasn’t that what music was supposed to be about? I never again doubted it.

5. August 16-17, Woodstock Festival, Bethel, New York.

Through a farcical series of errors and misfortunes, I wound up seeing only one day out of three, but on the plus side, unlike most of the audience, I completely avoided getting rained on. Some performances – like those by Sly and The Family Stone and The Who – will live forever in my memory, while others, Janis Joplin and the Grateful Dead among them, were underwhelming. For me the real takeaway from this event was its own event-ness: the idea that something could cause half a million people to decide to express themselves and their (counter)culture by showing up and sitting in a muddy field for three days. In the years that followed, I would stand and sit in far worse places for the sake of music, so I’m no one to talk.

6. August 28-September 8, 1970: Sky River Festival, Washougal, Washington.

Although I was there for all 10 days of one of the longest and most DIY festivals in history, I can’t tell you the name of a single band. It didn’t matter; the real point was making Sky River the festival that would never end. Your ticket doubled as a deed to the derelict farmland where it was being staged on, and all money raised was to go toward developing it into a rock and roll commune where we would live forever. We were digging wells and building shelters long before the bands stopped playing, but the simultaneous arrival of Washington’s unrelenting rainy season and an unsympathetic county sheriff put a harsh end to our dream. We haplessly waved our ticket/deeds to demonstrate our right to be there, but the ink ran and the paper crumbled in the downpour as the sheriff bundled us on down the road. I resolved to lay a firmer foundation the next time I tried to launch a new civilization.

7. March 12, 1980: The Go-Go’s, The Old Waldorf, San Francisco.

In 1979, I saw the Go-Go’s, dressed in garbage bags and still learning to play their instruments, open for my friends’ band, the Pushups, at the Mabuhay. A year later, still cherishing their ramshackle charm, I went to see them again at a larger, more “professional” venue. I barely recognized them; just like that, they had turned into one of the best bands in the world. As they played some of the songs that would turn up on their first album, it was impossible to stand still, and even more impossible not to get caught up in the exuberance and emotion. I was furious to discover that once again the Go-Go’s were only the opening band. They were hustled offstage after an obscenely short set, to be replaced by an annoyingly “zany” ska band called Madness who I’d barely heard of at the time. Some of us booed and demanded more Go-Go’s, but when it became obvious that wasn’t going to happen,, I left and went down the street to the punk club. As it happened, I would never see the Go-Go’s again, but I’ve always consoled myself with the certainty that at least once I’d witnessed them at their absolute stunning best.

8. March 15, 1980: The Ramones, Pauley Ballroom, UC Berkeley.

I saw the Ramones a bunch of times; once they were poor to mediocre, most of the other times, somewhere between very good and excellent, but on this Tuesday night in 1980, they were transcendent. Somebody announced that it was Iggy Stooge’s birthday (as a former Ann Arborite, I’d never been able to get on board with that “Iggy Pop” nonsense). It turned out not to be true, but nobody knew or cared, and the event became a giant dance party in his honor. I don’t know if the Ramones ever paused to take a breath during their hour-long set; the crowd definitely didn’t. As freaks and weirdos, many of us had missed out on the wild and crazy dances in the high school gym that mostly only existed only in the movies anyway. This was our night to make up for it. When it was over, I stepped out onto the balcony and wrang what looked like a bucketful sweat out of my t-shirt. My attitude toward music from then on became: if I can’t dance to it, you can go to hell.

9. May 1988, Operation Ivy, Gilman Street, Berkeley, California.

Almost every Op Ivy show deserves to be on some sort of “greatest ever” list, but if I had to choose the one most special to me, this would be it. They played right after returning from their first (and, it turned out, only) tour. A few months earlier, Lookout Records, the label I’d helped start, had put out a 7” EP for the band, and they’d immediately taken off on a six-week national tour, which in those pre-internet, pre-cellphone days, was a daring, even reckless move for a virtually unknown band. It wasn’t all smooth going, but when they made it back, we welcomed them like champions. It reminded me of that first Supremes show. There might have been only a couple hundred of us as opposed to tens of thousands, and while the Supremes had sold a few million records, Operation Ivy were thrilled to have unloaded 1,000 copies of their 7”. But the sense of hometown pride was just as palpable. I’d always seen the East Bay as Detroit with palm trees, and like Detroiters, we often wore a chip on our shoulder about being overlooked or ignored. Now we too had our local heroes, and the rest of the world was going to have to pay attention.

10. November 1988: Sweet Children, a cabin in the mountains above Willits, California.

Our band, the Lookouts, had been around long enough to be the best (also only) punk rock band in the backwoods wilderness of Mendocino County. Our 15-year-old drummer, Tre Cool, told his high school friends that we’d play at a no-parents party in a rustic shack up, way up, in the mountains outside town. The weather turned bad, and almost no one showed up, not even the kid who was supposedly the host, so we had to break in, hook up a generator, and light some candles (this was way off the grid). The other band I’d invited from the Bay Area wound up playing for five kids sitting on the floor. They called themselves Sweet Children, and sounded like I imagined the Beatles would have when they were teenagers. Their 16-year-old singer-guitarist, who somehow managed to be both the shyest and most self-confident of the group, sidled up to me afterward to ask what I’d thought. Without thinking, I blurted out that I wanted to do a record with them. By the time the record came out a few months later, they’d changed their name to Green Day, and quite a few people’s lives had been irretrievably altered, with many more to come.

11. June 27, 1998: The Weakerthans, The Starfish Room, Vancouver, British Columbia.

Ten years later, my rinky-dink little label had sold several million records, which I had taken as a sign to quit and walk away from it all. I had no idea what a shock it would be, as if I’d had a substantial part of my soul amputated. For a long time, I wandered around in a daze, barely able to think about, let along listen to music. Then, while I was visiting Vancouver, Mint Records honcho Grant Lawrence talked me into going with him to see a new band called the Weakerthans. Fellow Winnipeggers Duotang were also on the bill, as well as Halifax’s wonderful Plumtree, but when Weakerthans singer John K. Samson began, in his plaintive prairie tones, to sing about “An all night restaurant, North Kildonan,” the music in me came roaring back to life. By the time the song ended with a soaring steel guitar, I was near tears. I must have seen the Weakerthans at least 25 times, all over Canada, the US, and Europe, and, when they were briefly label-less, even considered getting back into the business just so I could put their records out. Fortunately, that proved not to be necessary, allowing me to go on being purely a fan of one of the greatest – and nicest – bands ever.

12. January 1-8, 2017: The Lookouting, lots and lots of bands, Gilman Street, Berkeley, California.

I’d always been cynical, even scornful, about reunion shows. Nobody is ever as cool or as idealistic or inspired as they were – or seemed to be – back in the day. So when 19-year-old Alex Botkin approached me about reuniting 10 or 20 classic Lookout bands for a festival, I didn’t take him too seriously. “Half those people probably aren’t even speaking to each other,” I told him. Luckily he didn’t take me seriously, and instead set about contacting farflung band members and convincing them this would be a good idea. All but one band said yes, so many that the fest had to be extended from a weekend to a week. People flew in from all over the country and the world to relive their Gilman Street and Lookout memories, and Alex convinced me to come along as well. None of the bands embarrassed themselves, and most were as good as or better than ever, despite not having played together in years or even decades.

It’s always been a little awkward for me when people start gushing about what Lookout means to them. I’m flattered, of course, but part of me wants to say, “Oh, come on, it was just a record label. The Lookouting cured me of that. Watching the way the bands, the fans, and in many cases, the fans’ kids related to each other and to Gilman’s “sacred ground” (as Tim Armstrong of Operation Ivy and Rancid once put it) made me a believe. If it’s that big a deal to all you guys, I thought, who am I to disagree? The Lookouting showed me it was possible to treasure and respect the past without wallowing in it. Though it’s highly unlikely that I’ll ever start another record label or band, it’s kind of cool to remember those I once belonged to.

—

Larry is also author of the book How To Ru(i)n A Record Label: The Story of Lookout Records, which you can grab a copy of in our shop. While you’re there, add Op Ivy’s Hectic EP and the Punk USA: The Rise and Fall of Lookout Records book to your collection too.