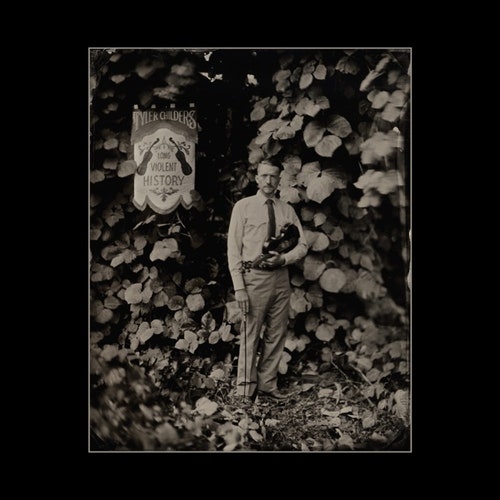

Listen to “Long Violent History” by Tyler Childers

In a heavy scene from Barbara Kopple’s 1976 documentary Harlan County USA, a white mother collapses weeping in front of her son’s open casket. During the historic strike against the Eastover Coal Company and Duke Power, miner Lawrence Jones was killed by a shotgun blast to his face, and a grand jury declined to indict the company foreman who pulled the trigger. It’s the kind of tableau that comes to mind when Tyler Childers howls about hauling boys off the mountain at the peak of “Long Violent History,” the anchor track to a surprise new album of fiddle tunes from the Kentucky native.

As Childers’ bow makes conviction-heavy draws, “Long Violent History” connects the bloody struggles of rural, mostly white mining communities to contemporary fights for racial justice. In Harlan County (and Blair Mountain, and Matewan, and Ludlow), miners rallied against companies that subjected them to wildly dangerous work conditions and other indignities, while police and the National Guard assisted bosses in their violent crackdowns. Knowing this past—and how people like Kentucky senator Mitch McConnell have used ignorance of it to their advantage—Childers bypasses embarrassing hand-wringing and white guilt for a potent dose of solidarity. He rejects pearl-clutching complacency with caustic humor, aiming directly at the unearned pride that feeds ignorant prejudice.

In a video explaining his intentions, Childers requests that his white, rural listeners empathize with the anxiety of Black Americans who live under the daily threat of police violence. He invokes fellow Kentuckian Breonna Taylor, whose state-ordained killers have still largely avoided professional and legal consequences, asking, “If we wouldn’t stand for it, why would we expect another group of Americans to stand for it?” Like the labor-struggle standard “Which Side Are You On?” (written by the mining activist Florence Reece), “Long Violent History” renews a plain call for moral clarity. By asking his listeners, “What would you do?” Childers invites us to consider more deeply what’s already been done.