In 1960, Françoise Hardy surprised her family—twice. First, she passed her baccalauréat exam with flying colors, a shock, really. Then, for her reward, she chose a guitar over a transistor radio. The radio had seemed the obvious fit: The introverted 16-year-old adored her piped-in tunes, becoming obsessed with chanson singers like Jacques Brel and then the English-language songs broadcast on Radio Luxembourg. Years later, Hardy likened her discovery of British and American pop artists like Paul Anka, Brenda Lee, and Cliff Richard to a coup de foudre (thunderbolt). “I immediately identified with them, because they expressed teenage loneliness and awkwardness over melodies that were much more inspiring than their texts,” she later wrote in her memoir. A guitar was a vehicle for her own self-expression and Hardy quickly began writing her own material, rare for a pop singer at that time.

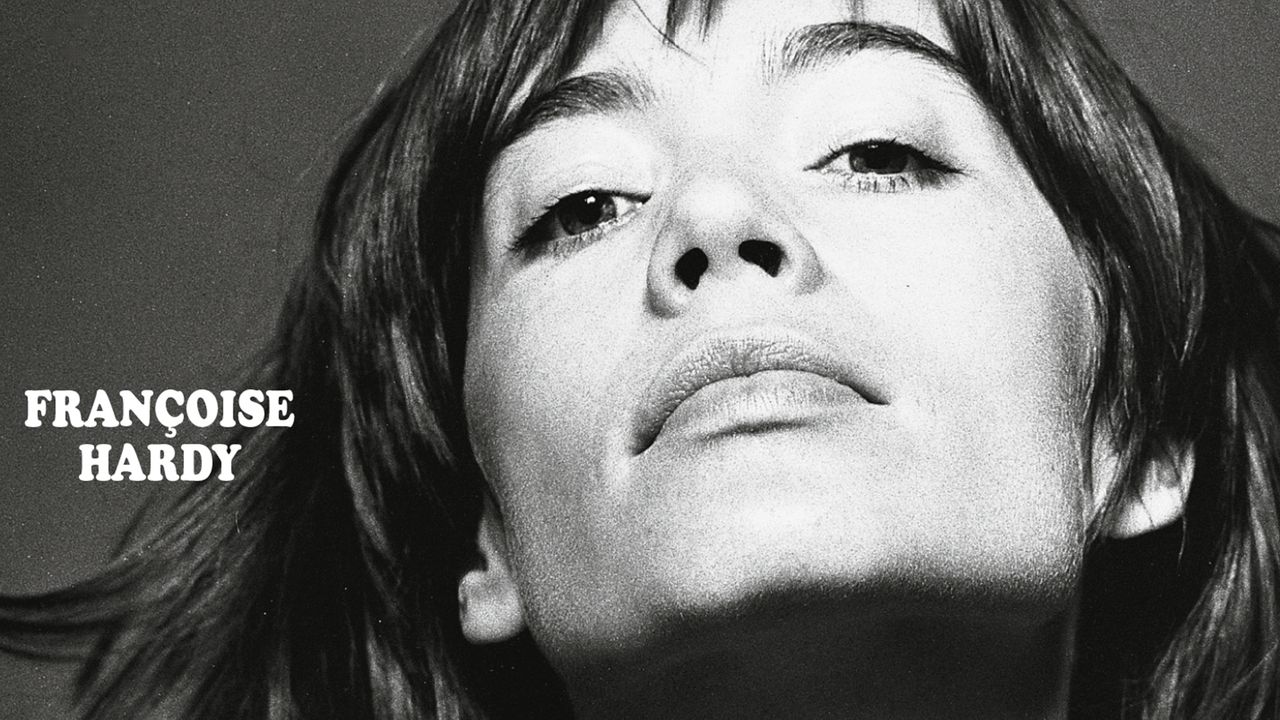

In 1962, after signing a deal with Disques Vogues, Hardy encouraged her label to promote one of her self-written songs, a wistful number called “Tous les garçons et les filles” (“All the Boys and Girls”). By the time she released her full-length debut a few months later, the song was an unexpected hit in France. The melancholic “Tous les garçons” set Hardy apart from bright-eyed contemporaries like France Gall and Sylvie Vartan. If the other yé-yé girls sang candy-colored love songs, here was Hardy, shyly peering out from behind her long bangs, lamenting the loneliness of her soul: “Et les yeux dans les yeux/Et la main dans la main/Ils s’en vont amoureux/Sans peur du lendemain” (“And eyes in eyes/And hand in hand/They walk in love/Without fear of tomorrow”).

By 1965, “the yéh-yéh girl from Paris” was a star overseas, earning her first and only English-language hit with a song titled “All Over the World.” Though Hardy was a natural homebody, she still found ways to enjoy her celebrity. She delighted in turning heads in avant-garde ensembles by modern fashion designers Paco Rabanne and André Courrèges. She did the movie star thing, appearing in films by Roger Vadim and John Frankenheimer. A cameo appearance in Jean-Luc Godard’s 1966 new wave film Masculin féminin cemented her spot as a generational icon. But the idea of Françoise Hardy often eclipsed the woman herself. “More than a singer, she’s becoming a universal myth with whom thousands of young girls dream of identifying,” opined the French magazine Special Pop in 1967.

As she matured, Hardy came to resent her early work and considered the arrangements “terrible.” “I listened to that record and I was so dissatisfied,” she once said of “Tous les garçons,” “and I have been dissatisfied very often ever since.” As soon as she had some acclaim under her belt, Hardy convinced Disques Vogue to let her record in London with the pop arranger Charles Blackwell and his orchestra. Hardy’s mid-’60s records reflect this superior production as she dabbled in balladry, baroque pop, and blues, releasing albums sung in Italian and English. She was well-prepared for the emerging singer-songwriter era—she had, after all, been doing both—and collaborated with a variety of fine songwriters, including Serge Gainsbourg.