“Alls my life I had to fight, nigga!”

During a peaceful 1963 demonstration against segregation laws in the city of Birmingham, Alabama activists were met with violent attacks from high-pressure fire hoses and police dogs producing some of the most disturbing and iconic images of the civil rights movement.

Fire fighters use fire hoses to subdue the protestors during the Birmingham Campaign in Birmingham, Alabama, May 1963 – Frank Rockstroh/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

“Alls my life I had to fight”

In 1921 the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma – an almost exclusively black neighborhood filled with thriving businesses was attacked by a mob of angry white residents. Dozens were killed. It’s christened the single most violent act of racial violence in American history.

Tulsa, Oklahoma after the race riots. Injured and wounded prisoners are being taken to hospital by National guardsmen – Hulton Archive/Getty Images

“Alls my life I had to fight, nigga!”

August 2014, police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown, an unarmed teenager, in Ferguson, Missouri, sparking national outrage and weeks of protests to follow.

A demonstrator protesting Darren Wilson’s shooting death of Michael Brown is arrested by police officers in St. Louis, Missouri – Joshua Lott/Getty Images

“Alls my life I had to fight”

August 2005, impoverished residents of New Orleans, many of them black, waited on government assistance after Hurricane Katrina ravaged Southeast Louisiana. Due to slow federal action, many would lack basic necessities like water, housing, and health care.

“When you know, we been hurt. Been down before. When our pride was low, looking at the world like where do we go. And we hate po-po, want to kill us dead in the street for sure. I’m at the preacher’s door. My knees getting weak and my gun might blow but we gone be alright.”

It was author and activist James Baldwin who said, in his 1956 book Sunny Blues: “All I know about music is that not many people ever really hear it. And even then, on the rare occasions when something opens within, and the music enters, what we mainly hear, or hear corroborated, are personal, private, vanishing evocations. But the man who creates the music is hearing something else, is dealing with the roar rising from the void and imposing order on it as it hits the air. What is evoked in him, then, is of another order, more terrible because it has no words, and triumphant, too, for that same reason. And his triumph, when he triumphs, is ours.”

Kendrick’s triumph is indeed our triumph on “Alright.” His decree of imminent victory in the face of terror pierces through our inter-mutual spirits even if for a moment. The song forces you to hear the volumes of tidings he arranged in less than 800 words. A dynamic message. The 2015 song which became an anthem for the Black Lives Matter movement will forever live on and exuberantly embody the power of hip-hop.

Five years after Eric Garner’s death, people gather in protest, July 17, 2019 in New York City – Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Chuck D and Public Enemy dubbed hip-hop the “black CNN.” This will always be the truest legacy of the culture. On To Pimp A Butterly, Lamar boldly and impenitently charges the menaces of capitalism, racism, and discrimination. A radical exposition of blackness in the current social context. A tale of our plight towards unblemished equality. Like Public Enemy and NWA did with “It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back” and “Straight Outta Compton” fashioned the way we view the world with his third studio album.

Pitchfork named Kendrick Lamar’s thought-proving single “Alright” from his black power manifesto To Pimp A Butterfly, song of the decade. In my opinion, TPAB is the most important rap album of this generation. So much of hip-hop is criticizing an analyzing systems of oppression – police brutality, poverty and social injustice in all forms.

In the same article, Pitchfork said, “It’s not every day, or even every decade, that a song will become platinum-certified, Grammy recognized, street ratified, activist endorsed, and a new nominee for Black National Anthem; that it’ll be just as effective performed before a massive festival audience or chanted on the front lines at protests; that it’ll serve as a war cry against police brutality, against Trump, for the survival of the disenfranchised. Inspired by a trip to South Africa, Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright” bears a message of unbreakable optimism in the face of hardship.”

Hundreds of years ago as slaves we sang joyful songs to get us through the daily brutalities of chattel subjugation. During the civil rights era, we marched as an independent army demanding the civil liberties that America continued to disallow. Now, years later, we still need this variety of music to heal from the dreary tangibilities of the time. It’s a feel-good record that reminds you of struggle’s beauty while inciting a resolve of altruism. Lamar boxes with hopelessness and optimism on an unforgettable beat. It is a beautifully conducted waltz in a ring of controversy.

Black people have been rebelling against the power structure through music for generations. The songs we sang during slavery had to be partially euphemistic; the messages hidden in the complexity of the linguistic gymnastics we still do. It was the bedrock for the ways we speak today. It was our own little undetectable, daily uprising in passing. In many ways, this is hip-hop’s precursors. Ta-nehisi Coates described how rap gave him the earliest sense of what writing should mean. This stated in his New York Times best-selling book Between The World and Me. I feel the same as Coates. Listening to these street journalists reporting from and for the unrepresented voices in America shaped my social consciousness. This too was my earliest inkling of literature’s true power and purpose. was my Shakespeare. my Allan Poe.

I was about 10 years old when I first experienced a protest. In the city of St. Petersburg two white police officers had killed an unarmed, teenage black motorist. After the police department refused to shared information the community became furious. I remember ducking down in the car as projectiles flew threw the air and the muffled rumble of chants filled the cool Florida air. Right after that experience was when I first heard “The Point of No Return” by Ghetto Boys. I found refuge in the song’s lyrics given the anger I felt – not fully understanding the gravitas of this situation but knowing that I always saw other black men dying on the news at the hands of police.

“Alright” was chanted during protests and rallies in the years since its release. As songs of my early youth gave me a form of solace in times of unrest so did this composition. Due to its social timing and indignation of black America, the song quickly grew into the soundtrack to calls for justice. The track grew popular in the shadow of several high-profile police killings which involved unarmed black men.

“I’m fucked up, homie, you fucked up but if God got us then we gone be alright.”

Part avouchment, part affirmation. The song’s hook proxies its brilliance. Under Kendrick’s commanding voice we all collectively wrapped our arms around each other in a show of unity and asserted that – even if it does not feel like it right now – we will be okay. And further, we are in this fight together. We symbolically linked arms across the nation in a season of new awakening driven by feelings of cheated social impartiality.

A cocktail of hope, anger, depression, “Alright” harvests some deep-rooted theoretical analogies long tied to the black psyche in terms of the false perception of America’s dream. Kendrick’s disposition expresses a glimmer of hope shrouded in equal resignation. He’s torn. Back and forth Lamar goes, a display of internal struggle. Pleased with the progress yet contending nothing has ever changed. Wrestling with the idea that given oppression’s stronghold, will things ever truly change?

The balancing act between hopefulness and sadness. The weight on his shoulders. He speaks for a group of people. He’s trying to tell people to rise up: you have the talent, you have the talent and ability and promise. The other side is accepting the realities of the world we live in. Even though he’s Kendrick Lamar, a celebrity, when everything boils down he can just as easily be another statistic. A powerful message. Giving yourself a chance to believe.

Several other artists have made songs that speak to the same conviction as those articulated in “Alright.” Each era of hip-hop has had a commensurate anthem. The 80s had “Fight the Power” by Public Enemy and “Fuck the Police” by NWA. The 90s had “Changes” by 2 Pac. The 2000s have “Be Free” by and these songs hang in the rap section of black history’s esteemed gallery of art.

Hip-hop artists haven’t just written songs about change, they’ve been consistently linked to activism. ’s halftime performance at the Super Bowl, with an outfit honoring the Black Panthers, was an unforgettable moment. ’s “Vote or Die” campaign during the 2004 Presidential election. J. Cole and Talib Kweli joining demonstrations in Ferguson, Missouri after Mike Brown’s shooting.

The messages conveyed in “Alright” by way of To Pimp A Butterfly are reinforced through Kendrick’s performances and the song’s visual artistry. Lamar stood on top of a cop car during most of his 2015 BET Awards performance. Here he directly accosts the power structure not of law enforcement but of injustice. In his set, the police car works as a physical embodiment of the inadequacies in criminal justice. Demonstrations like the Watts riots of 1965 produced images reminiscent of Kendrick’s show.

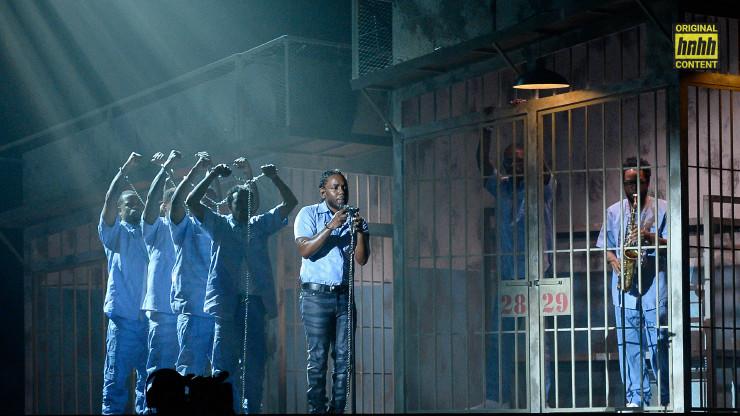

During his 2016 Grammy performance, Kendrick came out with faceless soldiers who represented the disenfranchised and exploited people upon which the American dream is built. This is further highlighted by the initial soundbite “America, God bless you if it’s good to you.” Turning the ideological motif “God Bless America” on its head. This acts as a perfect precursor to his performance of the song “XXX” which references both gun violence and police brutality against blacks.

Kendrick Lamar performs in shackles at the 2016 Grammys – Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images

Dave Chapelle came out during an interlude of the same performance to remind the audience that “the only thing more frightening than watching a black man be honest in America, is being an honest black man in America.”

Kendrick was interviewed during Austin City Limits. The moderator asked him, “When you write a song or make a record do you think about how it’s going to affect people. The impact that it could have?” K-Dot responded, “Prior to this album, prior to a lot of my new music – a lot of the records were just for me. It was more of a selfish type of thing. Until I seen that people out here actually connect with it just as deep or even more than me writing it. So, now I go into the aspect of how can I make something that’s personal for me but also personal for that’s listening to it. So, when I go in to make a record like that. To Pimp A Butterfly. I go in with the mind state that it has to connect. Not only for me and my culture but for people from other walks of life. People around the world.”

One of the most lasting and polarizing images involving the song came in Cleveland, Ohio. In unity and solidarity, protesters began chanting “we gone be alright” after being pepper-sprayed by police. A viral moment that echoed across the digital sphere. This song was that rare moment James Baldwin spoke of – when we truly hear the music and its message. When the undeniable connection happens between artist and consumer. With “Alright” Kendrick’s triumph was our triumph.