No one will ever explain the core appeal of Def Leppard more accurately than this lyrical excerpt taken from the band’s website:

“Women!”

[guitar solo]

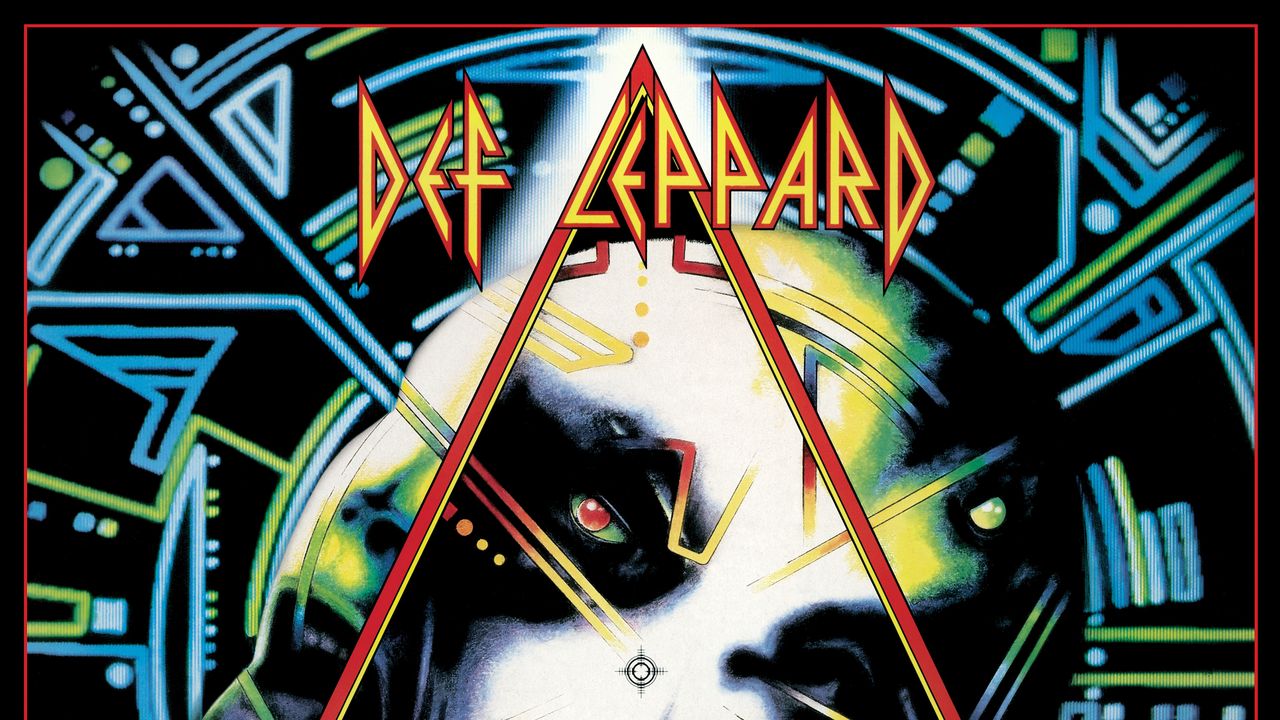

The song is called “Women,” and there is no better way to introduce the most expensive album ever created at the time.

But for nearly a year, the most successful album of its time began with the sound of failure. Hysteria spun off enough inescapable hits to make over half its 63-minute runtime instantly familiar to anyone within earshot of a July 4th classic-rock block. The lead single wasn’t one of them. Def Leppard were, above all else, worried about the metal cred they forfeited the moment they showed up on MTV looking like themselves, i.e., a Van Halen that more closely resembled Duran Duran.

So in the video for “Women,” Def Leppard play a bunch of schmos in a box factory, a far cry from who they’d become by 1989’s Live: In the Round, In Your Face—the most successful starting five to hold court in the homes of the Denver Nuggets and Atlanta Hawks. “Women” peaked at No. 80 on the American charts and isn’t included on Vault, the 1995 greatest-hits package that includes previously unreleased tracks and something from The Last Action Hero. It’s still an awe-inspiring teaser of Def Leppard’s state-of-the-art pop metal, a song that might be more beloved if it had been the seventh single, rather than the first. “I heard that Stevie Wonder and Prince had commented on how great it had sounded when they first heard it,” guitarist Phil Collen told Apple Music, which, I need receipts here. Some albums are too big to fail, but “Women” is a necessary reminder that Hysteria once appeared doomed to failure because it was too big—the work of a band that lived out their dreams of being the next Led Zeppelin only after pulling the Hindenburg out of a tailspin.

At this point, even the most casual Def Leppard fans can recount the beats of Hysteria’s tragic origin story more readily than the lyrics of “Pour Some Sugar on Me.” Singer Joe Elliott contracted mumps as a grown-ass man and, naturally, was worried about its notorious side effects on the “nether regions” (“They swell up like elephant balls,” he informed Rolling Stone). If Hysteria’s lyrics (and tour lore) are to be believed, Elliott did just fine for himself. Guitarist Steve Clark was deep in polysubstance addiction that would take his life in 1991, yet the guitar parts on Hysteria are so pristine, they sound quantized. You cannot hear the hundreds of bottles of vodka and whiskey that littered the practice space.