When Aya Sinclair was a teenager growing up in Huddersfield—a town in the north of England between Manchester and Leeds—she felt herself come to life in the swell of Christian rock. Someone sang about the Lord and blissful frisson radiated through her. Sinclair believed that feeling was the Holy Spirit. She joined a Pentecostal church. She worshiped. Then she felt another stirring. At first, it manifested as a sneaking aversion to the path laid before her: a university education, marriage, children, a nice job, a quiet home in the suburbs. The shadow of convention squeezed the air out of her life. She realized she might be queer. Sinclair confided in her church’s leaders, and they told her to keep herself locked in the closet or leave. She left. She went to Manchester, got into clubs, started making dance music, started using drugs, transitioned, found euphoria bubbling far, far away from the Holy Spirit’s reach.

Sinclair’s debut album as aya, 2021’s im hole, paired derealized drone confessionals with gabber-lite wallops. It was, she’s said, a ketamine album, an attempt to render the effects of the drug on the body by retooling the framework of the dance song. Standout “what if i should fall asleep and slipp under” is, structurally, pop, with verses and a refrain that you might call a hook if aya hadn’t hollowed out its beat and tossed it in the gutter. “Come over, we could fuck the void out of each other,” she teased, her voice slithering through waves of distortion, like she was promising a unilaterally bad time.

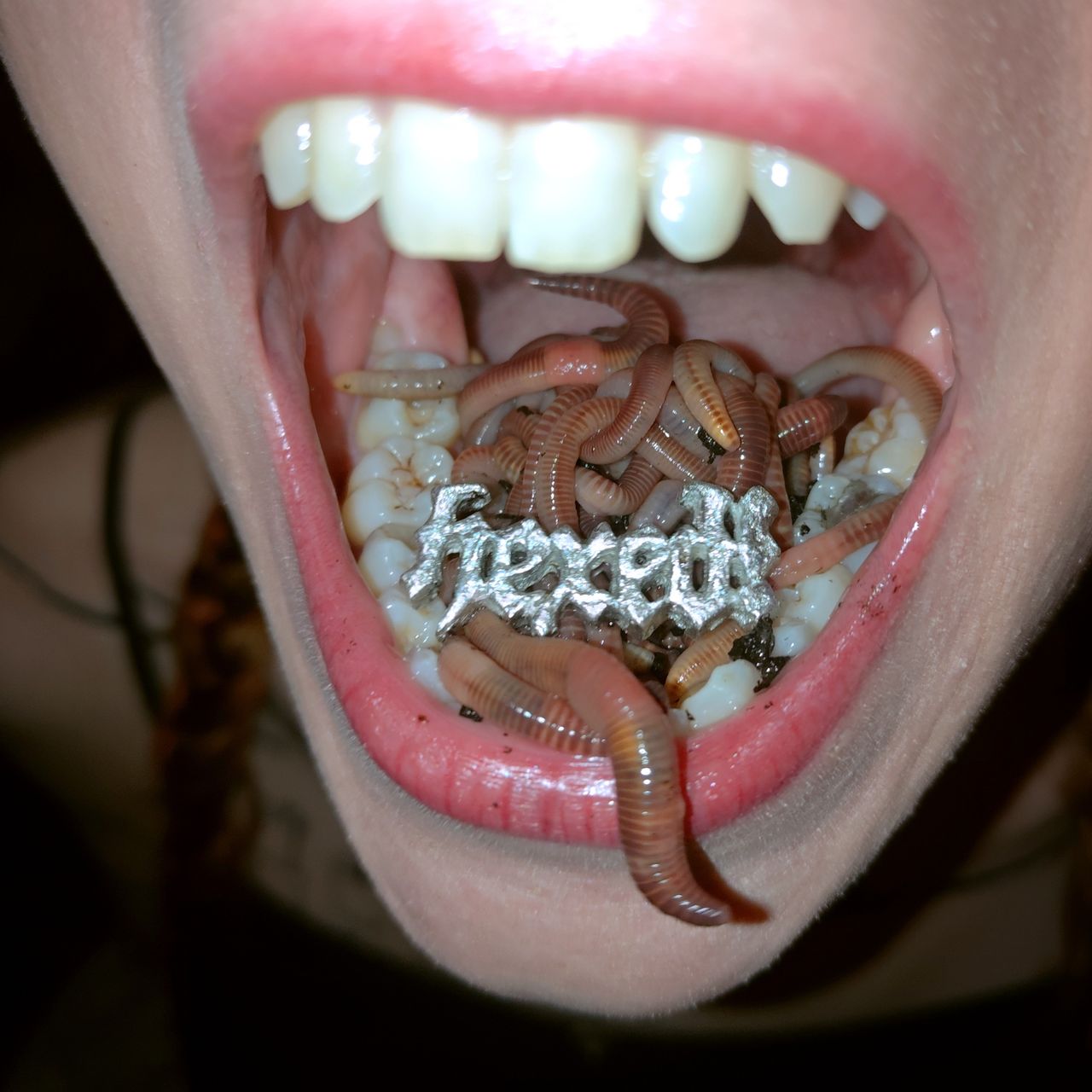

Now based in South London, aya wrote and recorded her second album, hexed!, from the perspective of early sobriety. During the first months of her recovery from substance abuse, she dug back into the memories she carried from her most acute terrors: cocaine-fueled all-nighters, dissociative panic attacks. The album roves, swarms, and stews like a mind starving for intensity, galloping along to the next high on bleeding legs. Deep in its mesmerizing glut are some astonishing works of synthesis. Sound bristles, foams, bursts, and oozes, lashing its acid against aya’s newly ferocious vocals. She presided over im hole like the emcee in Mulholland Drive’s Club Silencio scene: with wry, knowing diction, a little smirk on her lips, secure in the knowledge that none of what was happening was real. On hexed!, it’s real. She knows it. She tries to keep up the cool facade and she keeps getting dragged into the furnace.