If only your timing had been better, if only your city had been cooler, if only your debauched nights had been crazier, and if only your bleary-eyed confessions the next morning had been more candid, maybe you could have been Mac DeMarco. A dozen years ago, soon after leaving Canada’s great western prairie for Montreal and then New York, DeMarco skyrocketed into Millennial spokesbro status, the perpetually hungover interlocutor of generational disappointment who became shockingly and enduringly famous.

But if you didn’t happen to be smitten by the unabashed snaggletoothed fuckup who made silly faces beneath a ubiquitous wide-brimmed ballcap, the enduring question was: Why? DeMarco sang like Kermit the Frog wooing Miss Piggy or every scrawny boy coughing up sad songs at a house show while everyone else hunted duct tape for a round of Edward Fortyhands. His guitar playing was distinct but circumscribed, as if he’d once mastered a few dozen tabs on Ultimate Guitar inside his childhood bedroom and determined that was sufficient for rock’n’roll. He wrote with remarkable clarity, limning his struggles at the edge of oblivion and ascent with welcome levity, but that alone has rarely been enough for massive popularity. If you lived in a scene of any size, you knew a DeMarco, maybe even were one yourself. Why, then, did he become the Mac DeMarco?

The answer, at least for me, has never been clearer than on Guitar, DeMarco’s beguiling sixth album and his first set of non-instrumental hijinks since 2019’s tender and damaged Here Comes the Cowboy. There’s been an inordinate amount of big life stuff for DeMarco in those six years. His semi-estranged father died (as did his cat, Pickles), and he left Los Angeles for a ramshackle seaside sprawl in British Columbia. He gave up booze in 2020 and cigarettes two years later, salubrious milestones for someone whose Brooklyn sty was so stained with smoke it gave a hardy Pitchfork reporter an eye twitch. He turned 30 and, a few months before Guitar’s arrival, 35. He survived, and he grew up.

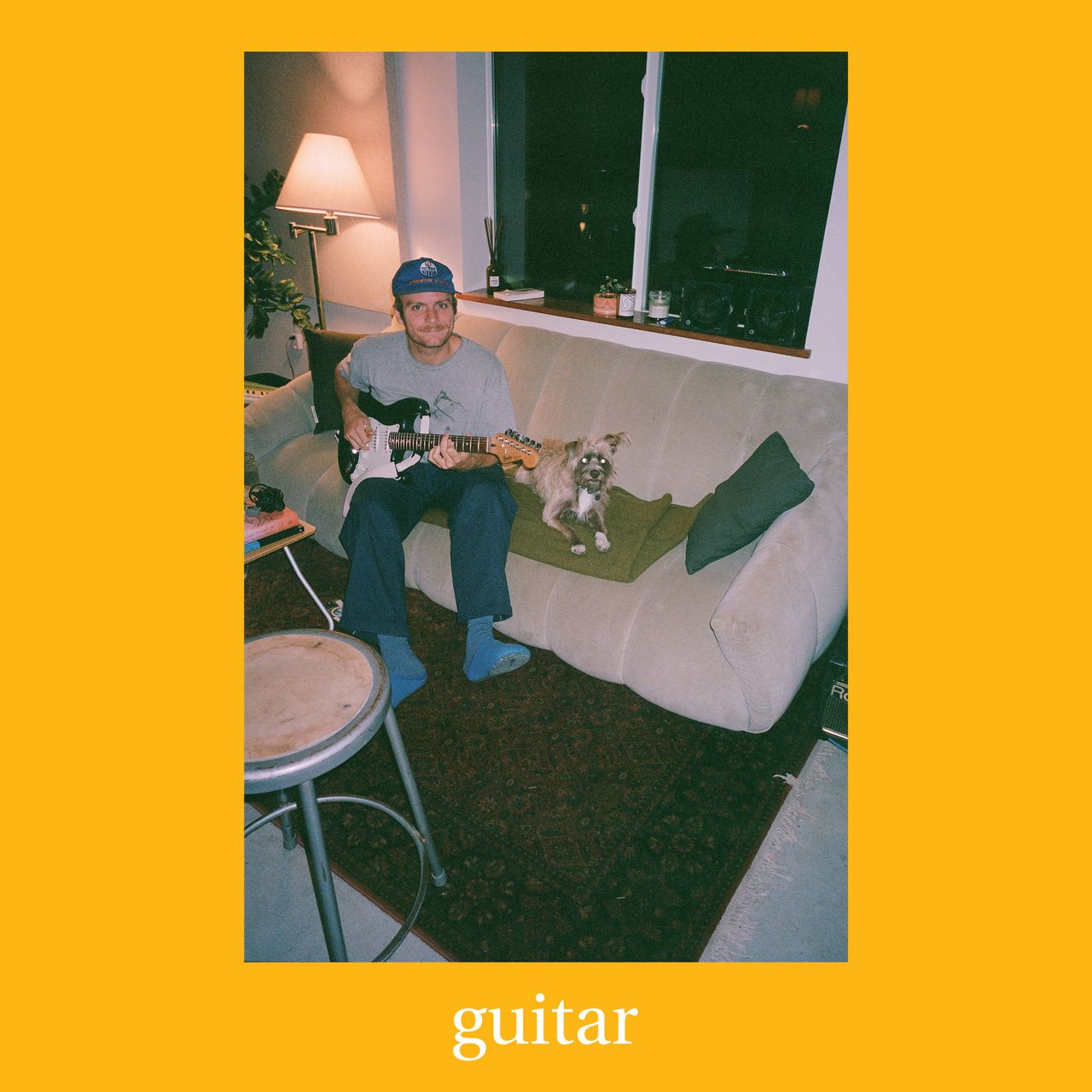

These dozen songs are the work of someone turning around to survey the damage, then turning back ahead in hopes that the way forward clears a little bit. Played and captured entirely by DeMarco in two weeks at his home in Los Angeles late last year, Guitar foregoes all of the synths and tricks of his prior records, with an electric, an acoustic, and simple bass and drums buttressing a voice that has never sounded so beleaguered, hopeful, and real. DeMarco’s music has always offered a pedestrian kind of escapism, allowing you to glimpse inside the mind and times of someone you might have been; on Guitar, he finally starts to escape his past for himself. This is DeMarco’s most direct and confident expression ever—OK with being a little sad, happy to have the chance to get over it.