Thus spoke Butt-Head: “Whoa. Girls. Whoa! These chicks rock.”

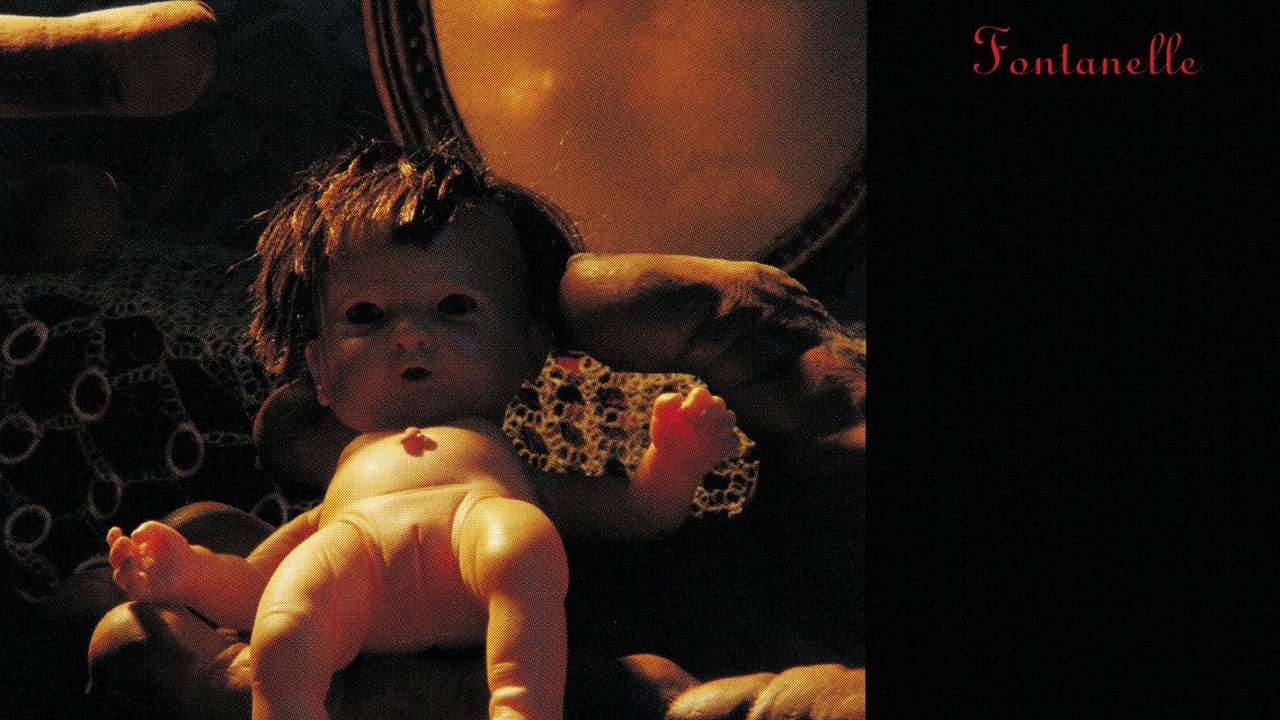

Babes in Toyland’s “Bruise Violet” echoes across the MTV airwaves, as teenage cartoon delinquents Beavis and Butt-Head headbang and air guitar to the song’s music video. “Is that Cindy Brady?” Beavis jokes, taking in frontwoman Kat Bjelland’s whipped platinum blonde hair, white babydoll dress, bright red lipstick, and piercing blue eyes. “Shut up, Beavis, these chicks are cool,” replies Butt-Head. The pair watches for a rare few moments of silence as footage of the Minneapolis three-piece thrashing their way through a set at CBGB alternates with scenes of Bjelland encountering a series of identically dressed doppelgängers. She strangles one of them, played by the renowned photographer Cindy Sherman. (Sherman’s photo of a creepy baby doll adorns the cover of Fontanelle, the album on which “Bruise Violet” appears.)

As Bjelland snarls the song’s refrain of “Liar! Liar! Liar!,” Beavis, mishearing, begins chanting, “Fire! Fire! Fire!” (An exasperated Butt-Head says, “Shut up, assmunch. She said ‘Liar.’”) Beavis continues his “Fire! Fire! Fire!” chant with every chorus, until Butt-Head intervenes: “Don’t make me kick your ass again, Beavis. We’re missing this video, and it doesn’t even suck.”

It was the summer of 1993, and Beavis and Butt-Head was the most popular show on MTV. The animated hooligans were, arguably, the most influential rock critics in America. If an up-and-coming artist’s video made it through their gauntlet of juvenile insults unscathed, a career would be jump-started. Just ask Rob Zombie.

Indeed, the Beavis and Butt-Head endorsement was the apex of Babes in Toyland’s short-lived commercial success. Fontanelle, their major label debut, had been released in August 1992. Despite reams of positive press, and the rising tide of next-Nirvana mania, the album had only sold around 50,000 copies by the start of 1993—a respectable number, but hardly enough to justify the amount of promotional resources Warner/Reprise had been spending on the band. But between the Beavis rave and a booking on the generation-defining Lollapalooza tour, things were looking up for Bjelland, drummer Lori Barbero, and bassist Maureen Herman. The label serviced a “Babes and Beavis and Butt-Head in Toyland” version of “Bruise Violet” to radio and Herman appeared on the Lollapalooza ’93 cover of Entertainment Weekly. Sales began to climb; Fontanelle would go on to sell over 200,000 copies.

In October 1993, a five-year-old boy in Ohio burned down the mobile home his family lived in, killing his younger sister. His mother claimed that Beavis and Butt-Head’s pyromaniac tendencies had inspired her son to play with matches. Almost immediately, MTV altered any episodes that referenced fire, including the one featuring “Bruise Violet.” The Babes video was replaced by a Butthole Surfers video for all subsequent re-airings. Even now, clips of the original version can only be found in obscure corners of the obsessive fan internet.