‘Five Nights at Freddy’s’ Is Worth About Five Minutes of Your Time

It’s tricky to put a fresh coat of paint on the old killer-robot movie, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be done. Successful spins on the genre have included time-traveling assassination attempts (The Terminator), a satire of tourism and America’s romanticized frontier (Westworld) and noirish ruminations on exactly how humans differ from the artificial life they create (Blade Runner). It seems that if we’re going to watch bots go bad, we want to have some bigger ideas to chew on while we do.

Five Nights at Freddy’s, this year’s bot-based Halloween offering from Blumhouse Productions, has plenty to chew on — maybe too much. Drawing on quite a trove of source material, including a dozen-plus video games and a novel trilogy, it strains to erect a supernatural universe while neglecting to fulfill the basic promises of a scary film built on a gag premise, stretching its dreary tale of trauma to nearly two hours. One pines instead for the splattering violence, cynical script and forthright chintziness of a cult techno-horror trip like 1986’s Chopping Mall, in which zealous security robots dispatch an entire gang of horny teens trapped in a galleria over a brisk 76 minutes. Or Blumhouse’s own smash hit M3GAN, from just last year, which demonstrated the value of camp humor when terrorizing characters with an evil toy.

But Freddy’s is invested in making people, not its ghoulish machines, the stars of the show, and suffers for it. After the inaugural kill of a panicked security guard running from an unseen menace only to wind up clamped into the sort of lethal device you’d expect from the Saw franchise, we meet Mike Schmidt (Josh Hutcherson), a down-on-his-luck schmuck who is guardian to his young sister Abby (Piper Rubio) but can’t connect with her or her fantasy world. He loses his own security gig at a mall after assaulting a man he believes to be abducting a boy — we come to learn that Mike in childhood witnessed the kidnapping of his little brother Garrett, who was never seen again — and an estranged aunt takes the opportunity to file for custody of Abby, supposedly so she can collect the government checks.

That ploy is a bit undercooked, no doubt (who, exactly, is getting rich off child care subsidies?), but we need a motivation for Mike to accept the new security job suggested to him by an unsettling career counselor (the always entertaining Matthew Lillard). See, it’s a graveyard shift, and Mike likes to spend his nights returning to the scene of Garrett’s disappearance in a kind of deliberately induced dream-memory so that he can try to recall an overlooked detail that would solve the mystery. If you’re wondering why we have this Nolan-esque psychological gimmick grafted onto the story of a deathtrap arcade haunted by animatronic beasts, well, you’ve picked up on how Freddy’s divides its focus to disappointing ends.

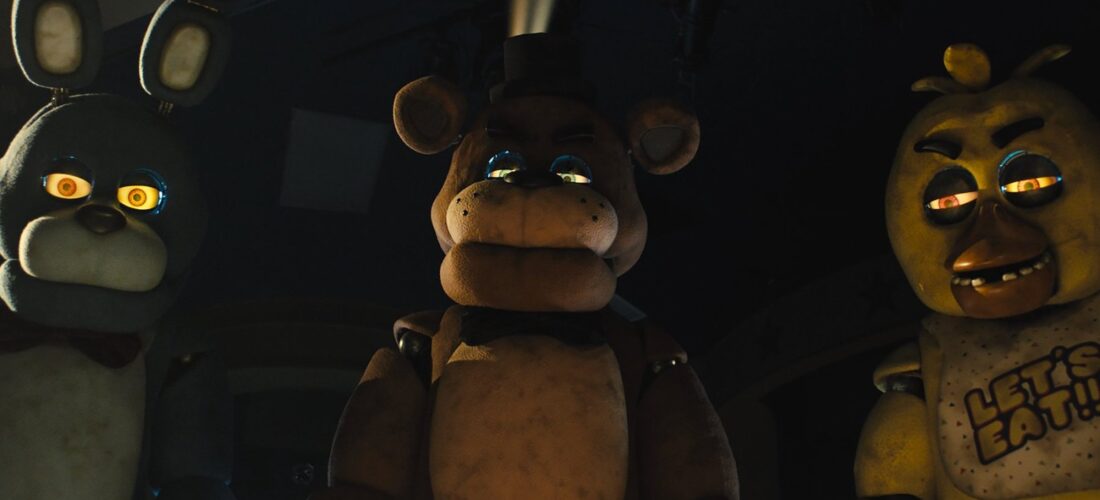

Mike accepts his situation and shows up to guard a decrepit, shuttered Freddy Fazbear’s Pizza establishment, which any viewer will instantly recognize as a stand-in for Chuck E. Cheese. It’s an eerie setting, complete with glitching lights, unexplained sounds, and an ensemble of half-functional animal automatons that presumably once led choruses of “Happy Birthday” for shrieking, sugar-crazed kids. These creations, from Jim Henson’s Creature Shop, are suitably garish, though they never gain much in the way of individual personalities. The real trouble with this setup is that the movie doesn’t exploit it: we neither delve into the rot of corporate nostalgia nor find this peculiar environment generating the suspense we crave. Only toward the finale, when a terrified Abby hides from the bots by submerging herself in a ball pit, is there a brief reminder of how the abandoned playplace might have been used to the fullest.

Only toward the finale, when a terrified Abby hides from the bots by submerging herself in a ball pit, is there a brief reminder of how the abandoned playplace might have been used to the fullest.

Slowly, a tedious lore begins to knit together, thanks to the visitation of Vanessa (Elizabeth Lail), a cop who patrols the neighborhood and knows about Freddy’s reputation for frightening off its night watchmen. Once she lets slip that the venue closed down because of a slew of kidnappings in the 1980s, Mike, who regularly sleeps on the job in his continued investigation as dream detective, intuits that the haunting and his brother’s case may be connected — and that Vanessa knows more than she’ll admit. Soon, he brings Abby along to camp out in his office, and he’s alarmed to discover that she regards the robots with familiarity, identifying them as her “friends,” or companions he had always taken to be imaginary. They, too, are worryingly energized by her presence.

By then, of course, we’ve already been treated to a few more murders; the bots are far more efficient when it comes to eliminating low-level crooks who break in during the daytime as part of a convoluted scheme by Mike’s aunt to cost him his employment and therefore the custody battle over Abby. Yet this sequence — like the rest of the film — is played maddeningly straight, sparing us any jokes or jumps. Given the cartoonish antagonists, you’d expect at least a tongue-in-cheek moment of self-awareness. Freddy’s lurches droid-like in the opposite direction, somberly building its not-that-interesting mythos.

Maybe that tack is more engaging for the puzzle-box survival games that spawned this adaptation. And maybe the novelty of pizza franchise mascots run amok will satisfy less demanding viewers. As a narrative that pretends to plumb the dark absence of missing children, however, Five Nights at Freddy’s is curiously inert, unwilling to get under your skin even as it grows dense with explanations of what’s happening. It’s unfair to compare the menacing robot bear to Freddy Krueger, the iconic kid-killer who shares his name, but it has to be said: that guy could nail a sick punchline.