The sci-fi TV show Stranger Things was successfully pitched with a remix. Its creators, the Duffer Brothers, cobbled together a fake trailer featuring clips from Steven Spielberg’s E.T. with its soundtrack replaced by the menacing synths of horror king John Carpenter. The effect was, according to Matt Duffer, “really fucking cool.” That integration of the vaguely familiar with the eerily sinister would power the show like it did for 2011 pastiche film Drive, itself working like Tangerine Dream put over Death Wish II.

Together, they served as a rebuttal to 30 years of the received wisdom of “’80s nostalgia,” the gags about asymmetrical haircuts and Rubik’s Cubes that permeated slop like The Wedding Singer and The Goldbergs. It was a way of communicating through vibes instead of hack references, a Proustian madeleine for survivors of an America scarred by nuclear anxiety, exploding space shuttles, Satanic panic, Chinese stars, lawn darts, and Punky Brewster’s friend getting trapped in the fridge. Do you want new wave or do you want the truth?

The Zoltar machine that predicted all of this was a 125-second YouTube clip of the obscure 1983 arcade game Laser Grand Prix soundtracked by a loop from Chris de Burgh’s saccharine 1986 ballad “The Lady in Red.” Uploaded in the summer of 2009 and currently standing at 4.3 million views, the video—titled “Nobody Here” after its cycling, haunting refrain—would serve as something like an a-ha moment for people who craved something deeper than A-ha references, a big bang for a generation of musicians attempting to live on the edge of memory and imagination.

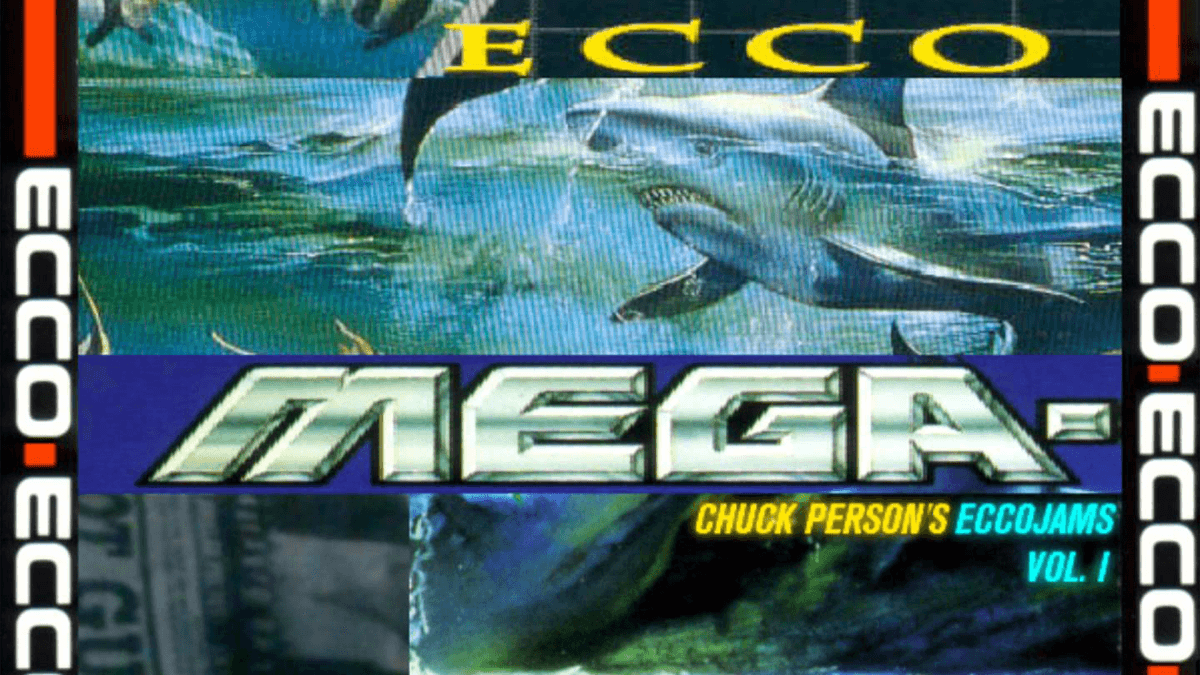

“Nobody Here” would reappear as the untitled 12th track on Chuck Person’s Eccojams Vol. 1, a profoundly inauspicious release—put out on a cassette, limited to a mere 100 copies, no text on the shell, no text on the back of the J-card. The artwork, borrowed from the box art of the tranquil Sega Genesis game Ecco the Dolphin, was close-cropped to feature a frowning shark instead of the playful cetacean. It would become the most influential cassette tape of the 21st century.

Released in 2010, Eccojams was a collection of 15 remixes all with the same concept: the dross of radio’s past, slowed down, echoed, and run through some dream-logic computer effects. Songs both familiar and unfamiliar transmogrified into a sleep paralysis slurry of half-remembered traumas. Putting Toto’s “Africa” in Grand Theft Auto: Vice City conjured the cool ��’80s of Don Johnson blazers, neon lights, and DeLorean doors. Putting Toto’s “Africa” in the Eccojams funhouse conjures the lived ’80s of wainscotted hallways, dust-caked mini blinds, station wagon interiors yellowed from cigarette smoke, lawns speckled with white dog shit and cathode ray TVs that play “The Star-Spangled Banner” at 4 a.m.