Twelve years and a seemingly unfathomable stylistic gap separate Giorgio Moroder’s bubblegum origins and the icy erotic panache of “I Feel Love,” his history-changing 1977 hit with Donna Summer. You might detect a similar gulf between “I Feel Love” and Midnight Express, Moroder’s first soundtrack project, even though the latter followed his robo-disco masterpiece by just a year. Directed by Alan Parker and written by Oliver Stone, Midnight Express was based on the memoir of a hapless young American hashish smuggler, Billy Hayes, who served five years of a life sentence in the Turkish prison system before making his dramatic escape in a stolen rowboat. But “Chase” turned the grim, violent, often xenophobic movie into disco gold.

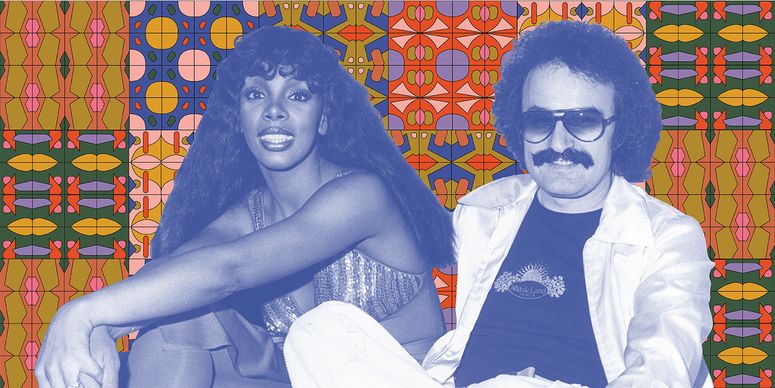

By mid-1978, Moroder had released 11 albums and produced fistfuls of hits for Donna Summer, while his Musicland Studios, in Munich, had turned out records by the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, T. Rex, Iggy Pop, and even Faust. Yet he’d never scored a film. Moroder wasn’t the filmmakers’ first choice, in fact. American Film magazine reported that co-producer David Puttnam wanted Electric Light Orchestra, but after negotiations with the British prog band went nowhere, Parker cut the film to a provisional soundtrack of previously released Vangelis material. When Vangelis, too, was unavailable, Puttnam turned to Casablanca Records head Neil Bogart for help; Casablanca’s film division was behind the production of the movie. Bogart, who loved Moroder and Summer’s 1975 Casablanca Records hit “Love to Love You Baby” so much that he requested a side-long extended version of it—he deemed it “a beautiful, great balling record”—suggested Moroder for the gig.

Parker flew to Munich to meet with the Tyrolean composer. There, he showed him the Vangelis cut of the film and asked if he could write a synthesized score. Moroder later recalled, “Basically, he liked the music I had done for ‘I Feel Love.’ And there’s one scene in the movie where a guy escapes and he said, ‘Give me something in the style of “I Feel Love”’—something like a bassline that gives the feel of him escaping, to get some suspense. And he liked the piece I did. And the rest was very easy.”

“I Feel Love” was probably the last thing on the mind of viewers who first encountered “Chase” in the cinema. The song turns up early in the film. After being arrested at the Istanbul airport with foil-wrapped packets of hashish duct-taped to his chest, Billy is taken by a mysterious American—whether consular officer or spy is never made clear—to the city’s central market to finger the dealer who sold him the drugs. The mood is ominous, colored by a gravelly synthesizer drone. (Moroder has professed his fondness for Tangerine Dream; their influence clearly colors the Midnight Express score’s atmospheric passages.) As Billy gets up from his table in a crowded cafe and feints left at the front door, the telltale arpeggios of “Chase” kick in, and the chase is on.