Only three sense memories remain from the night my wife and I came home from the hospital after our daughter died, 10 years ago this May. My brother, sleeping like a dog on the couch behind us, a miserable sentinel. The warmth of my wife’s hot tears and breath on my face, inches from my own. And something else, in the background, playing over and over again: Sufjan Stevens’ Carrie & Lowell.

Why would we do that to ourselves? The album that opens with “Death With Dignity,” the one whose most memorable chorus is a whispered “we’re all gonna die.” And yet I kept returning to the record player, flipping the album over and over. The album functioned as the bleakest kind of prayer, the one that doesn’t even ask for things, just offers a beseeching glance skyward: Notice me. Feel me.

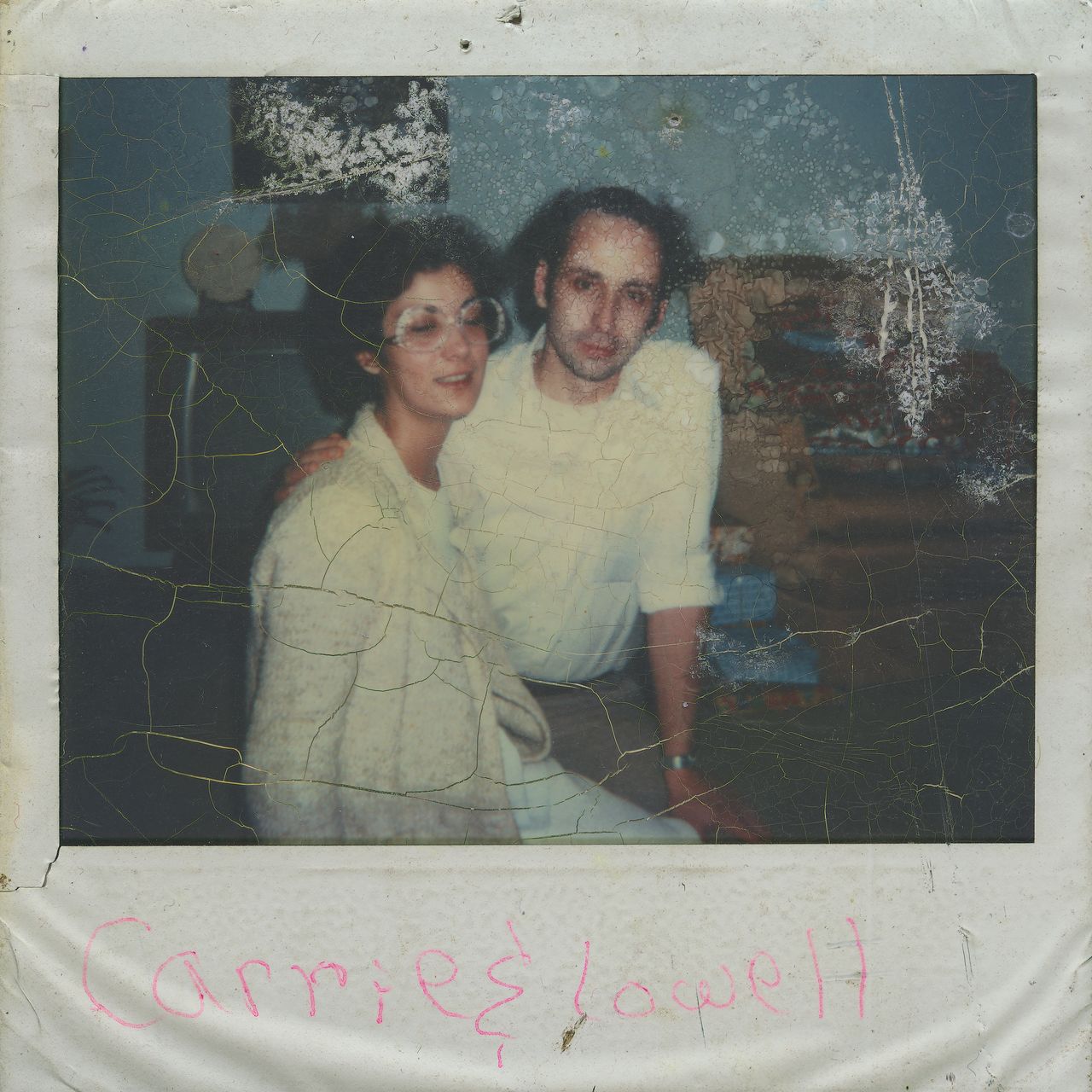

In the myopia of my shock and early grief, I barely registered the complicated and brutal autobiographical truth of the record. Yes, it’s an album with a Polaroid on the cover, clearly from a personal collection, paired with two first names. Yes, the lyrics are so specific to one man’s experience as to approach the forensic: “When I was three, three maybe four….” And yet the thumbprint of tragedy, the outline and silhouette of grief, was all I needed from Carrie & Lowell. I gulped at it, greedily, again and again. My relationship to an album has rarely been more intense. Until this month, I couldn’t bear to put it back on. To me, it had become like a death march, or a funeral mass: music for use.

But Carrie & Lowell, newly reissued by Asthmatic Kitty with a modest addendum of bonus tracks and a gorgeous 40-page photo album, survives my bloodshot fixation because it is so formally perfect. The arrangements feel inevitable in the way the harmonic motion of a Bach suite feels inevitable. There isn’t a single breath on the album that doesn’t feel drawn with specificity. Play the opening of “Death With Dignity” while staring at a creek, and the rhythms of the opening guitar figure will naturally match up with the flow of the water.

There aren’t many artists who can capture and preserve this intimacy and intensity. There is an obvious comparison to Elliott Smith, who similarly matched up a shaky and tender vocal with arrangements that felt like you could stare straight through them. But not even Smith bared his soul as directly, simply, and plainly as Stevens does here. Smith was often obfuscating or misdirecting in his lyrics even when it seemed he was confessing, but Stevens lays it all out: times, places, dates, car models. The familiarity that I get from these songs is the same I get from a short story collection rooted in a specific setting—the Nevada of Claire Vaye Watkins’ Battleborn, the Wyoming of Annie Proulx’s Close Range. Stevens’ memories become sacred the more granular they become.