Although the Bulgarian State Television Female Vocal Choir formed less than a century ago, with a verifiable context and history, writers and listeners still treat the ensemble’s music with the same mystification reserved for the pyramids of Giza, the menhirs of Stonehenge, or the cave paintings of the Neolithic age. Their demonstrations of the human voice are exceptional, presenting new possibilities as they transcend the mechanics of the throat, the grain of the body.

The shock of encountering sounds this extraordinary tends to bypass familiar categories and break into the realm of the inexplicable. The music baffles. But beneath its mystification lies a compelling story of folk repertoire, Communist propaganda, and the repeated suppression—and reimagining—of cultural identity, distorted by Western commerce and the label that reads: “world music.”

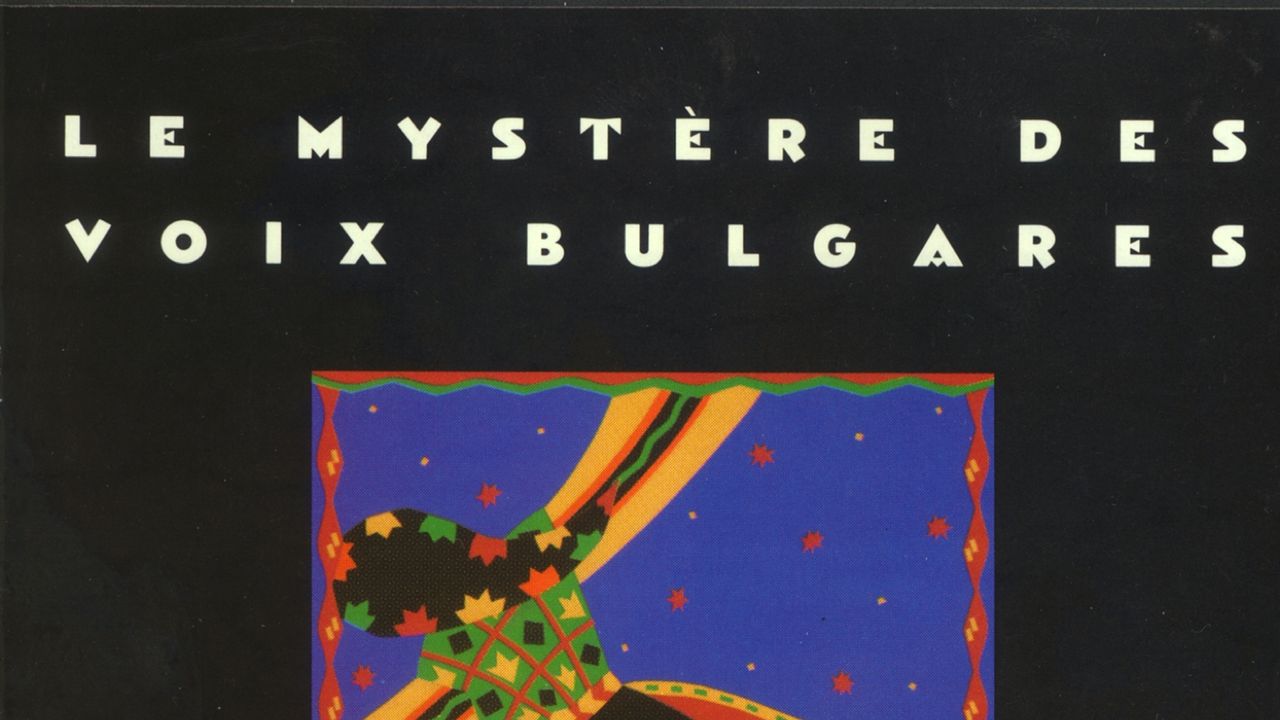

In 1986, the British label 4AD—followed by U.S. distributor Nonesuch in 1987—reissued a little-known 1975 anthology of recordings of the Bulgarian State Radio & Television Female Vocal Choir licensed from Swiss musicologist Marcel Cellier: Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares. Originally released on Cellier’s private Disques Cellier label, the album documented a government-employed ensemble singing modernized versions of Bulgarian village songs.

The ensemble was first formed in 1951 by composer Filip Kutev, who reworked monophonic village tunes into multi-part harmonic arrangements that drew from Western choral singing while preserving the ardent throatiness of Bulgarian folk. His scoring, which blended Bulgarian rootsiness with avant-garde, bore traces of Stravinsky’s grandeur, Debussy’s impressionism, and Schoenberg’s atonality, and resulted in a new musical genre called obrabotki (“handling” or “editing”).

In 1987, 4AD and Nonesuch’s reissues both charted in their respective countries and sold hundreds of thousands of copies; the album even soundtracked David Bowie and Iman’s wedding. A second volume, released by Disques Cellier in 1987 and 4AD the following year, went on to win a Grammy.