Depending on your age, taste, and life circumstances, you might see Brian Wilson as the sunny figurehead of youthful innocence; the tortured ideal of artistic integrity; the paragon of mastercraftsmanship; or a lovable eccentric who played his grand piano inside a giant sandbox. The common thread through all of these archetypes, of course, is that he endured. There has been a comfort in watching Wilson withstand the eras, knowing he might still pop up on concert stages or give strange squirrely interviews, proving by mere existence that some of us are immortal.

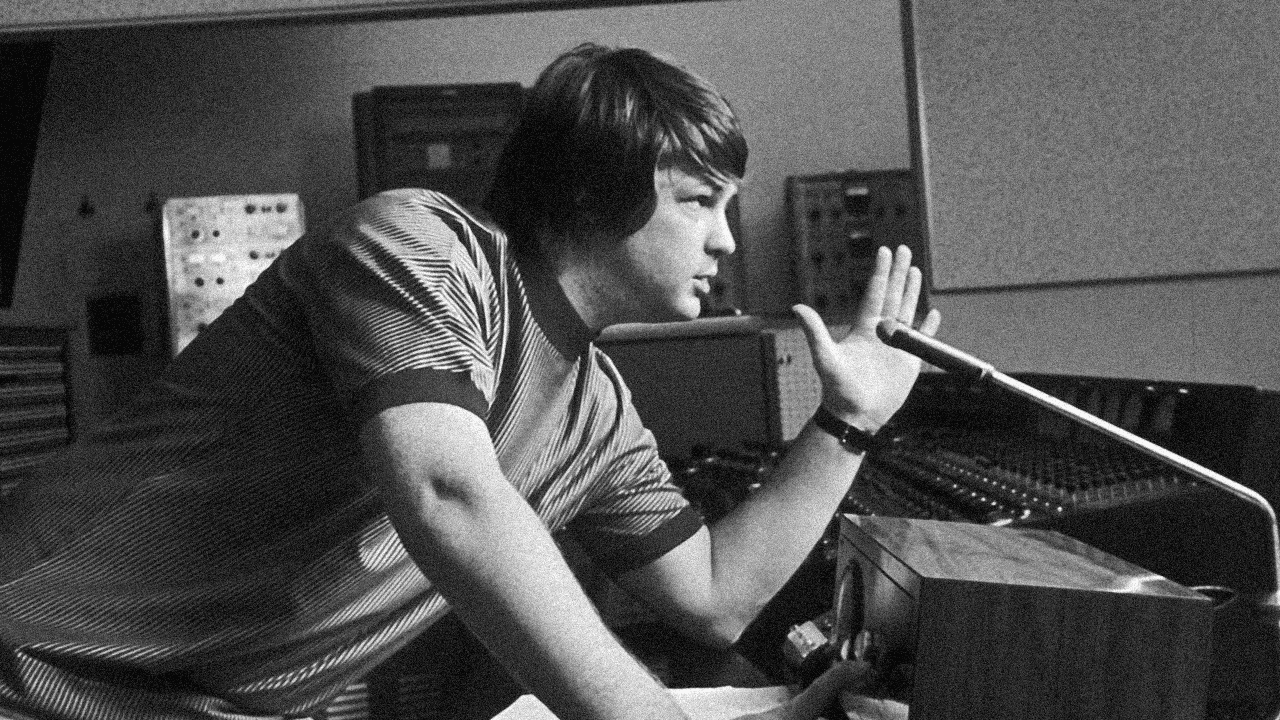

Even after his death this week at the age of 82, “immortal” is still the word that comes to mind. As a child in Inglewood, California, Wilson fell in love with music upon hearing George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” at his grandmother’s house. It doesn’t take long to clock what registered: the movement, the magic, the melody. Spurred on by the energy of Chuck Berry, the harmonies of the Four Freshmen, and the ecstatic production of Phil Spector, Wilson chased these highs through his vast, oceanic career. He was fiercely competitive—keeping up with the Beatles in the 1960s is partially what caused his nervous breakdown—but he was also tapped into an uncommonly deep well of intuition, understanding that the power of music was to communicate feelings that could not be expressed in words.

Accordingly, his legacy is not just in the songs he wrote; it is the breadth of his work and the way people connect to it. He is an artist who authored some of the best-selling records in rock history, as well as its most mythical lost album. He has made pop songs that seem woven into the fabric of life and some of the most stoned outsider art of his—or any—era. As an artist who, even in his 20s, felt he “just wasn’t made for these times,” he lived to see most of his work re-assessed and rehabilitated in the canon. In other words, he endured—which is a blessing and a curse.

Unlike the Beatles, the Beach Boys remained an active unit well into the 21st century, which means that digging through the back catalog is likely to turn up as many lost gems (like 2012’s surprisingly poignant reunion album That’s Why God Made the Radio) as bleak cash grabs (like 1996’s bizarre country project Stars and Stripes Vol. 1). And as Wilson’s mental health dipped and bobbed, he maintained a steady pace of live shows and new releases that occasionally seemed against his better interest, stirring concerns about his well-being and adding another, more troubling persona to his rolodex: the ghostly figure that fans might start worrying about.

Despite occasional glimpses into the darkness—in the 2021 documentary, Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road, he confesses that he “hasn’t had a real friend in three years”—Wilson never let anyone worry for too long. There is a Zen-like quality to his outlook, an unwavering consistency to his vision. Around the time that he scrapped Smile—the legendary project he began with Van Dyke Parks immediately after the creative breakthroughs of 1966’s Pet Sounds—he decided to let go of his voice-of-god perfectionism and start making smaller, sparer records that sparked more joy—pushing past the old obstacles by simply persevering. (To borrow a popular mindfulness phrase, “You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf.”)

Still, moments of profundity emerged. There’s a bleak, gorgeous song on the Beach Boys’ 1971 album Surf’s Up where he carries the thread that began with “I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times” to depressive new ends. It’s called “‘Til I Die,” and it’s one of the first songs that a new Beach Boys fan might hear and understand just how much emotional range they covered in their music. In its lyrics, Wilson describes himself a small, meaningless object in a grand universe with no control over his trajectory—a cork on the ocean, a rock in a landslide, a leaf on a windy day—and uses the mellow stormy music to guide him forward: “These things I’ll be until I die,” he sings in the chorus, as hopeless as he’s ever sounded.

As if proving his point, his bandmates were skeptical of the direction and suggested changing some lines: “How about instead of ‘It kills my soul,’ we sing, ‘It holds me up’?” Wilson temporarily acquiesced—you can hear that version on 2021’s Feel Flows compilation—but his original lyrics won out in the end. And while it’s more despondent than most of his characteristic work, it’s hardly an outlier. You don’t need to read the biographies or watch the 2014 biopic named after Wilson’s credo, Love & Mercy, to understand the desperate romance of “Don’t Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder),” or why “In My Room” suggests a level of introspection that goes beyond your average homebody. These were things Wilson couldn’t help but expose through the music, and once you caught them, you felt like you were invited into his mind as it reeled.

Through these songs, Brian Wilson wasn’t just teaching us to listen to music; he was teaching us to feel it. And for several generations of artists, he wasn’t just pushing them to create; he was pushing them to aspire. As with any artist who concerns themselves with themes of childhood and romance, his body of work is carried by a feeling of potential, utopia within grasp, his self-proclaimed “teenage symphonies to God.” This is likely why Smile is often situated at the center of his narrative. Here was an iconic artist with one of the most successful catalogs in recorded music—and his greatest album might be the one we’ll never get to hear. (An extensive reissue called The Smile Sessions, which collected studio outtakes from original sessions in the ’60s, was released in 2011.) For many people, hearing Brian Wilson for the first time was a sort of gateway drug into a life devoted to music as a higher calling.

This type of mythology is also what makes Wilson, paradoxically, one of the most popular cult artists of all time. I would pinpoint this transition to sometime in the ’90s, when he became situated within a canon of artists driven to the brink by their own creative spirit—he is name-dropped alongside figures like Syd Barrett, Scott Walker, and Nick Drake in the Chills’ “Song for Randy Newman Etc.” This was a world where Kurt Cobain was becoming a pop star, when the idea of “authenticity” became a rallying cry for art. Of course, Wilson’s authenticity was different from the rest of these figures. (After all, among his brothers, Brian wasn’t even the surfer!) But does anyone listen to the Beach Boys and wonder if he really feels what he’s singing? Even when he’s listing the planets in “Solar System,” you imagine a part of him that thinks he’ll start orbiting among them if he sings it well enough.

Within this subject matter—innocent wonder at the forces beyond us, heartfelt odes to simpler times, burnt-out submission to our loneliest depths—Wilson sought the connective tissue between all of us. It’s what kept him going. When asked in 2004 how he manages to stay active as an artist, he simply responded, “By force of will.” A decade later, he expressed pride that he had “proven stronger than many imagined me to be.” It’s a vulnerable statement from an artist who had spent his life struggling with mental illness, who lived under conservatorships, fought through multiple bitter legal battles, and operated at the forefront of a family band managed by an abusive father. There were times, I’m sure, when Wilson wouldn’t blame someone for betting against him.

Against these odds, he triumphed. Like few public figures, Brian Wilson is loved by all: From Paul McCartney (“No one is educated musically until they’ve heard Pet Sounds”), to Bob Dylan (“Jesus, that ear. He should donate it to the Smithsonian.”), to Bruce Springsteen (“The level of musicianship—I don’t think anybody’s touched it yet”). You would be hard-pressed to find a songwriter who hasn’t expressed his influence. Like the public domain songs he loved—“Shortenin’ Bread,” for example—his music belongs to everyone. It’s equally fitting for a young family on a road trip or a college freshman’s first experience with psychedelics; at weddings or funerals; in the collection of any self-respecting vinyl aficionado or the window of a Goodwill. There’s a reason why nearly every Beach Boys greatest hit set comes adorned with a sepia-toned image of the ocean on its cover, at some indistinguishable point between sunrise and sunset. It is priceless and free, at any time, forever.

This is why, when Wilson finally released a newly recorded studio version of Smile in September 2004, it still managed to feel new. Not just new, but exciting. At the time, I was just finding my footing with music discovery as a teen. I remember reading the five-star review in Rolling Stone and a glowing write-up on this website. Like the author of that review mentions in the opening paragraph, I was also a child whose father owned a copy of Endless Summer, and my understanding of the Beach Boys had been limited to those otherworldly pop gems about kids on the West Coast and the grinning, bearded faces on the cover. But when I listened to Smile, I heard another dimension to the same music that my dad loved—a lengthening shadow beneath the same sun. I found myself obsessing over its strange, sprawling arc, full of hymns and nursery rhymes, melody and mythos. It felt the way you hope your life will feel when you look back—all your joy alongside your dreams and fears and ambitions, all coated with a heavenly glow of getting to feel it all.