A woman drives fast along the California freeway with the radio screaming, delirious with grief. She does this every morning, dressing quickly in her Beverly Hills home so as to leave no time to think. Changing lanes is like a dance the way she’s trained herself to do it, seamlessly and to the beat. She walks barefoot into gas stations, rinsing down pills with warm Coca-Cola and chatting mindlessly with the attendants. Her marriage is over. Her showbiz career is dead. Her child has been taken away. She is known to cry at parties or get carried home; close friends have come to believe she’s insane. It is only on the freeway, when the music is loud, that she can forget what’s become of her life. To fall asleep she imagines herself on the road: “The Hollywood to the San Bernardino and straight on out, past Barstow, past Baker, driving straight on into the hard white empty core of the world.”

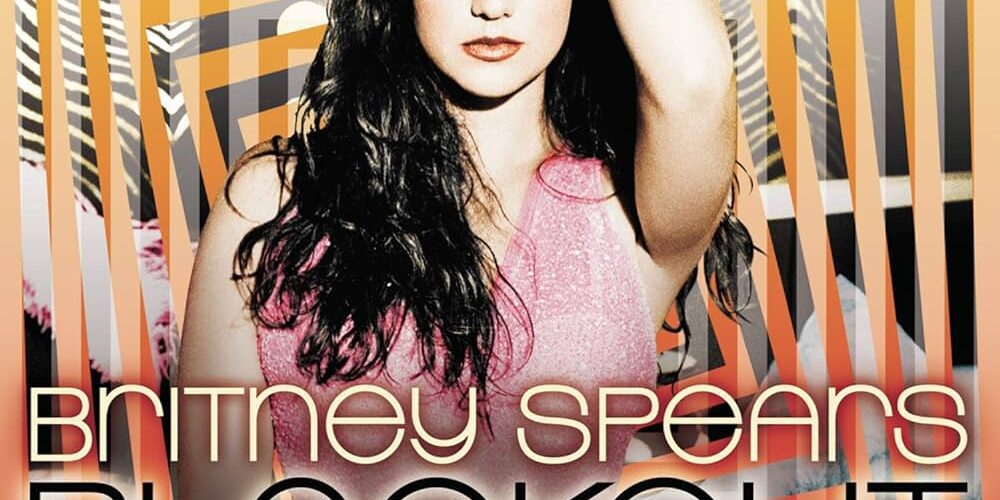

How chic the story sounds the way Joan Didion tells it in her 1970 novel Play It As It Lays. The woman is a trainwreck but a sharp and glamorous one, numbing out on pills as a critique of moral rot in 1960s Tinseltown. Books are great that way. Played out in real life in the year 2007, the tale loses its cool; now the woman is a punchline whose endless personal disasters keep a burgeoning new media economy afloat. It seemed that every week, or sometimes even every day, brought a hysterical new headline regarding the downward spiral of America’s pop princess. (“HELP ME!” “INSANE!” “OUT OF CONTROL!”) “We serialize Britney Spears. She’s our President Bush,” said TMZ founder Harvey Levin in a gruesome Rolling Stone cover story from early 2008, which began with Britney wailing in a San Fernando Valley shopping mall as a crowd closed around her with their Sidekick smartphones brandished. “I don’t know who you think I am, bitch,” 26-year-old Spears snarled to a shopgirl approaching for a photo. “But I’m not that person.”

What had become of the Southern sweetheart was not a symptom or appraisal of a new century’s decay but the foremost emblem of it, or possibly its cause. A New York Times essay that summed up 2007 as the year of the trainwreck, in which “prominent figures from every arena of public life did harm to their reputations and livelihoods in devastating fashion,” led with a description of Spears’ lifeless performance at the VMAs that fall. “Is there any measurable way to prove what many of us feel in our gut,” the article went on, “that 2007 was the year when the excesses of our most reliably outrageous personalities finally started to feel, well, excessive?” Or was it that the billion-dollar gossip industry, newly powerful online, had willed this chaos into being? It was the dawning of the era of perpetual surveillance, and websites once considered too sketchy to break news were scooping the “real” outlets when it came to all things shallow and macabre.