Black Star Sound Searingly Relevant On Their First Album In Twenty Four Years

In 1998, the year Black Star made their debut, shameless commercial rappers were the culture’s equivalent to co-workers who heat up fish in the office microwave. They were guilty of an obvious if prevalent faux pas that probably felt too good to abandon just for propriety’s sake. But Mos Def and Talib Kweli captivated the underground with their Boogie Down Productions–sampling single, “Definition,” whose charming raggamuffin vibes felt refreshingly organic—something like a soul-clearing sage to purify the bad stench on the scene.

The duo’s 13-track LP, Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star, was full of chakra-activating vibrations and pro-Black ideology. And Mos and Talib’s magical chemistry felt as rejuvenating and holistic as black soap and coffee-shop readings before they got stigmatized in the popular imagination as corny.

Arriving a year before Chris Rock joked on the MTV Video Music Awards about Puff Daddy’s saturation of the market, Black Star’s music felt reactionary. But Black star were the right group with the right, inspirational messages—about the boundless rewards found in gaining self-knowledge, escapism from the red-lined confines of the inner-city, Black women empowerment. And they came at just the right moment. The songs made you feel good inside your body when, after the murders of Tupac and Biggie, there wasn’t a lot to celebrate. And despite being branded with the “conscious” epithet, their messages weren’t preachy—anyone who told you differently was probably trying to sell you something.

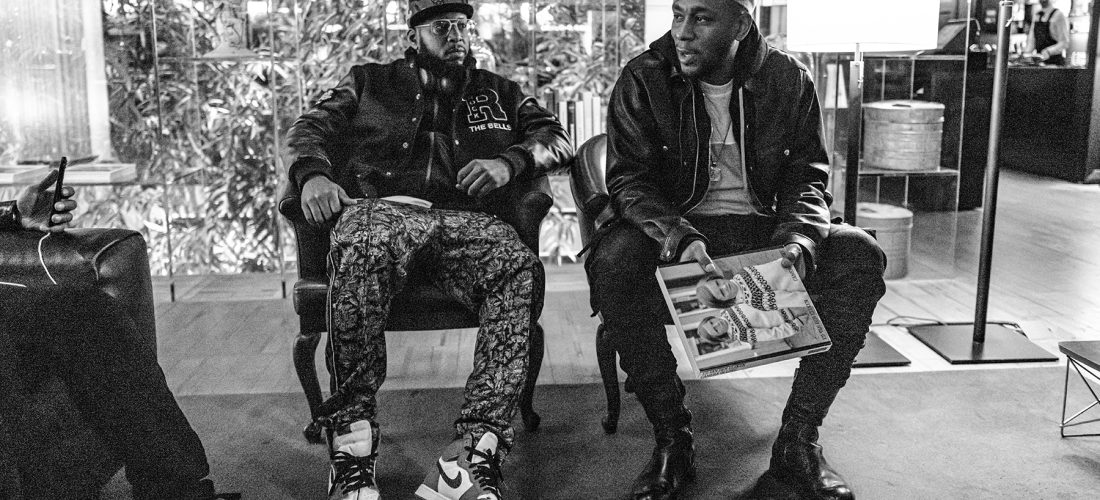

Whatever they do, Black Star don’t do clichés. No Fear of Time, their first album in 24 years is a concise and seamlessly flowing collection of insurrectionary rhymes and propulsive beats by one of rap’s most heralded duos.

On opener ‘O.G.’ Mos Def, who now performs as Yasiin Bey, starts his verse off with “Joy and pain, coin of the realm,” suggesting from the jump that the themes here are equity and maintaining balance. Though he’s been active these last few years, it’s thrilling to hear him with Kweli again, bringing his refined air, by way of Bed-Stuy, to Madlib’s crackling space-age symphonics. Bey’s impeccable diction makes every other word sound like it was composed with a Salt Bae flourish. When he raps, “All good for all hoods and palaces, poised throughout triumphs or challenges,” it resounds like a Mandarin manifesto for the 99 percent.

Kweli is even more to the point on the people-power salvo “So Be It,” where he insists, “My songs is knowledge to heroes that need honoring/A promise we demolishing all Confederate monuments.” Where Bey is breezy and abstract, Talib is urgent and laser-focused. At least two corrupt presidential administrations after they got their start, they still make toppling systems sound starkly amenable—like the aural equal to a classic Kara Walker silhouette.

And it’s all revolutionary love on “Sweetheart. Sweethard. Sweetodd.,” whose summery soul hiccups—like a beautifully warped dubplate of some dutty rock classic—feel dreamy and intense. It’s a callback to Bey and Talib’s celebratory “Brown Skin Lady,” reminding us, implicitly, that matters of the heart are as essential as Black lives.

The murky “Yonders” is a Romare Bearden collage of beautiful Old New York madness, featuring some of the duo’s most arresting wordplay. Over the cinematic strings and cruddy spine-tingling bass, Talib spits, “We born in killer hospitals with doctors who would abuse us/Carry boxcutters, there was other popular usеs.” Then Bey jumps in with a free-associative tangent (”Scarface chains so Miami got drapes drawn/Halloween, egg yolk, mustard gassing their face off”) that looms like the glorious collapse of a crooked empire.

The centerpiece of this nine-song opus, entirely produced by Madlib, is the jazzily titled “The Main Thing Is to Keep the Main Thing the The Main Thing.” It translates as a vehement deconstruction of self-help tropes and dorm-room-poster proverbs someone on Madison Avenue probably got rich off: Bey and Talib repeat “Everything is not for sale” as if it’s some populist mantra. The underlying motif is that material items are ephemeral, and art can’t be commodified. With their decades-in-the-making reunion album, Black Star proves that there’s no category for timelessness.