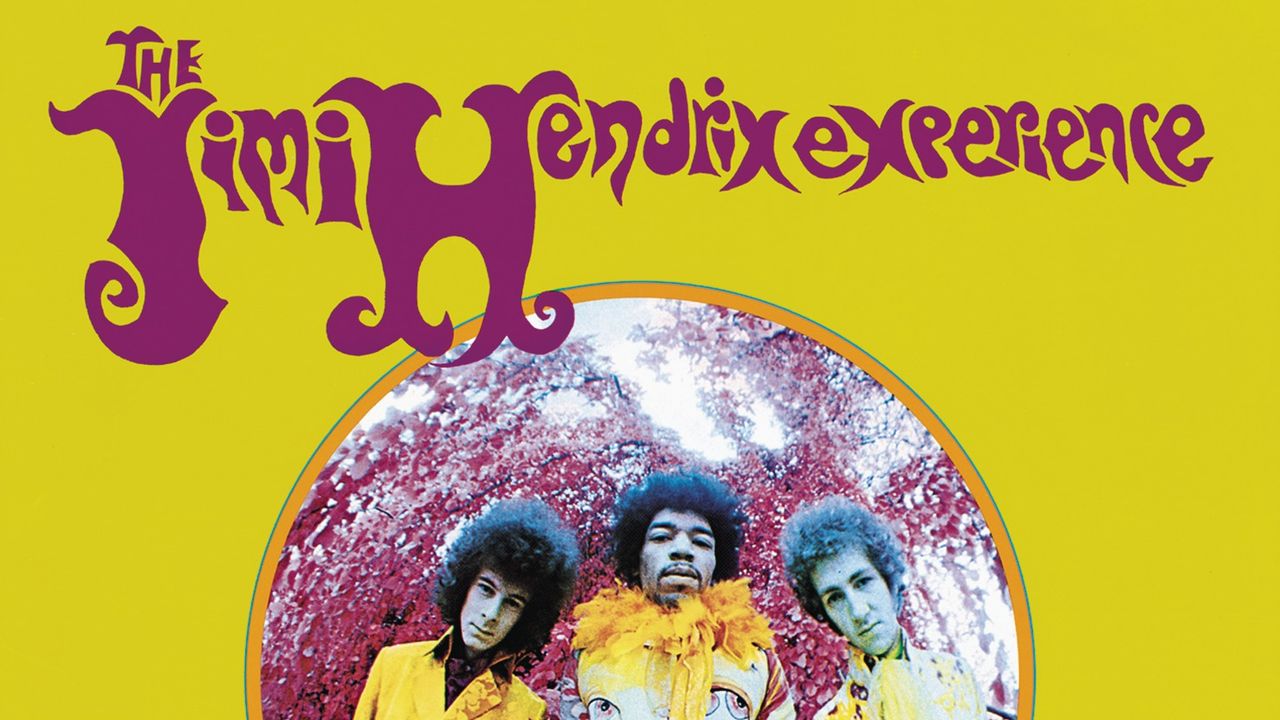

Jimi Hendrix did not want to be onstage at the Hollywood Bowl. A month earlier, in late July 1967, he and arguably England’s hottest new band—The Jimi Hendrix Experience, a riotous power trio formed in London only 10 months earlier—had bailed on their first full American run after opening for the squeaky-clean heartthrobs of the Monkees for eight disastrous dates. Though they were, by many reports, the loudest and most aggressive band on earth—with Noel Redding on bass and Mitch Mitchell on drums—they had not been able to compete with the hormonal pleas of American pubescence for the headliners.

Maybe, though, this silence was worse. Just before releasing their debut album in the States, the Experience had accepted the invitation to warm up the audience at the Bowl for The Mamas & The Papas, the sweet-singing “California Dreamin’” quartet so afraid to offend they’d cropped their first album cover to bowdlerize the toilet originally left in the frame. The Experience seemed to shock almost everyone into submission, the crowd so quiet Hendrix wondered if anyone was there at all.

“Right now, we’d like to continue on—drearily—with a song named ‘Foxey Lady,’” he said near the set’s middle, a moment that must have reminded him of trying to win over fans of Englebert Humperdinck’s saccharine numbers during one early European tour. Hendrix forgot the second verse to “The Wind Cries Mary” and barely bothered trying to recover. A bit later, he sighed: “Well, dig: We’ve got two more records to do, thank god.” The trio slashed into “Purple Haze.”

It was the Summer of Love, sure, but it was also the Long, Hot Summer, with ubiquitous race riots providing a warped mirror of the overseas escalation in Vietnam. The moment was charged. And so, this lilywhite crowd was having none of the Black man in his butter-yellow pants and bejeweled jacket, even if he was letting them off easy. The Experience had opened with “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” maybe the biggest song in the world at the moment, then covered Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, and Bob Dylan. They’d omitted the murder ballad that became their first overseas smash, “Hey Joe,” and didn’t come close to the despondent candor of “Manic Depression” or the astral slink of “Third Stone From the Sun.”

Sure, he played the guitar with his teeth and between his legs, but he didn’t set the thing on fire, smash it to bits, or, as best as anyone remembers, even pretend to fuck it. The most aggressive Hendrix got was to tell whoever happened to be listening to put their hand over their heart for “the American and British anthem”—a feedback-flooded assault on “Wild Thing.” Folks had spent their $1.50, however, to sing along to “Monday, Monday” on a Friday night, not to be confronted with a coming revolution. Hendrix was happy to be done with them, too.