Arath Herce Refuses to Compromise

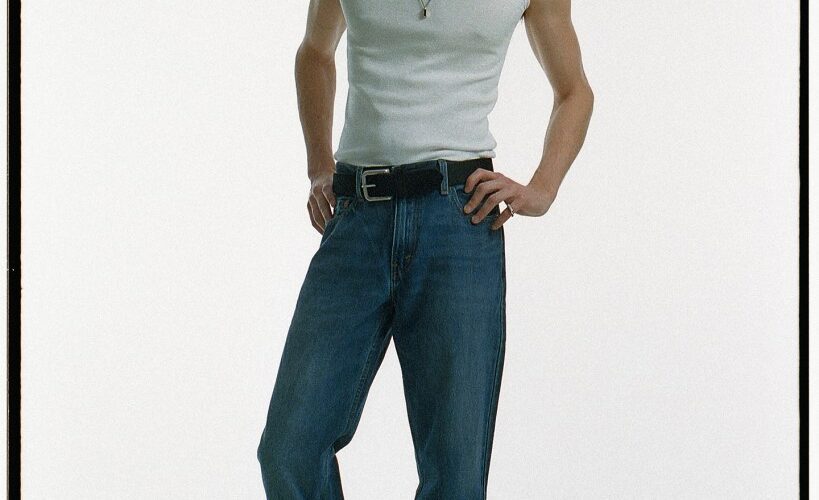

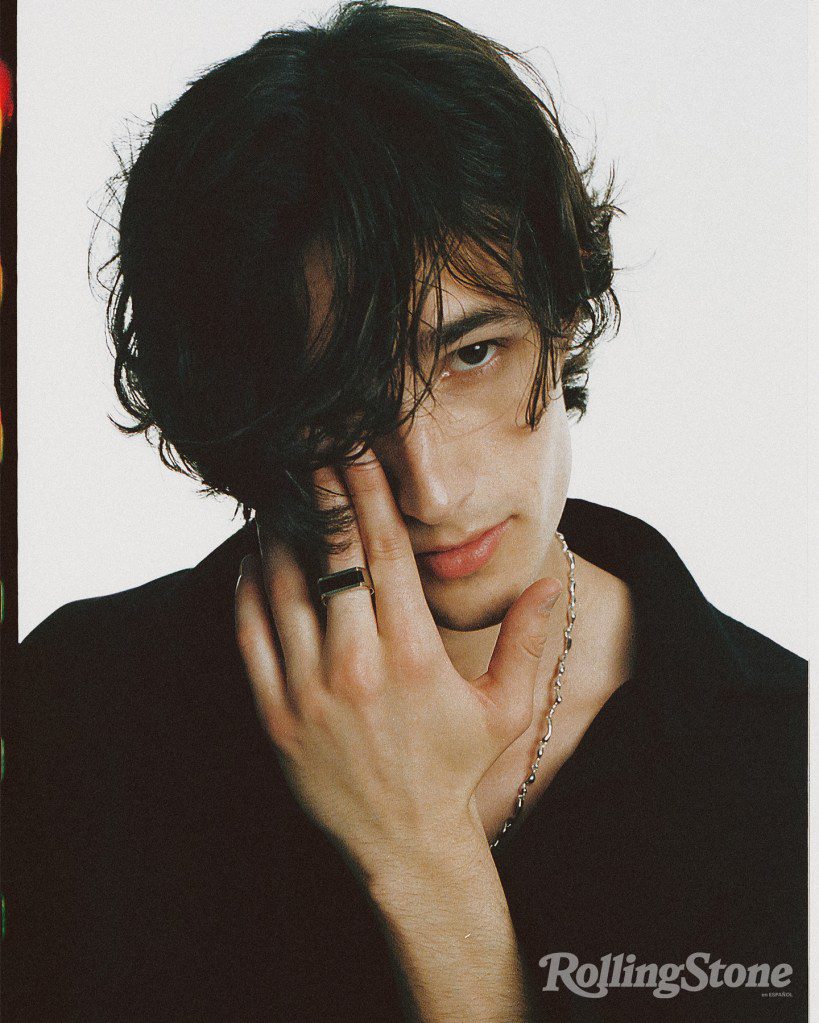

Arath Herce is in his studio in Mexico City, wearing an unbuttoned black shirt, jeans, and a silver chain with a single charm. He touches his face repeatedly, trying to hide his genuine shyness and saying things like, “I guess death haunts us all. It’s the only thing that makes life meaningful.”

Talking about life and death might not sit well with everyone, but it works for Herce. To some, his music can be pretty rock-oriented. However, his ability to intertwine poetic lines like, “I’d like to buy the rain / At whatever cost” with arpeggiated guitars and delirious piano keys produces a sound that recalls the Argentinian sounds of the late Seventies. Latin American artists are starting to name him as an influence when it comes to writing songs in Spanish.

He’s the kind of artist who isn’t interested in pandering to the recording establishment, and he’s certainly not begging for attention from luxury labels. He seems more interested in telling stories to find answers through them.

Although his parents were not professional musicians, his father used to play the guitar, and his mother was deep in literature and poetry. “I guess it all comes from those two worlds; my mom was more poetic, and my dad was more rock & roll,” he says. His father introduced him to the world of videos and songs by Elvis Presley, the Rolling Stones, and the Beatles. Meanwhile, he analyzed song lyrics with his mother; she taught him how to break down and interpret the meaning of each line. Herce was hooked on the idea of understanding the meaning of a whole universe hidden in a song. “I’ve always been timid. And I think I found a way to put my secrets in songs without anyone noticing,” he confesses.

Herce started playing the guitar with his father when he was eight years old. He would meet with several friends to play at home, where he learned a few chords. With just those couple of lessons, he unleashed his imagination and began writing songs. In the meantime, his mother told him something he would never forget: “A poem is like a song but without music.” Deep in a sea of verses and stanzas, he reflects, “Since I was a child, I’ve thought that writing a song was easy. So, with just four chords, I wrote my first song,” he recalls.

As Herce continued his studies, he quickly began developing his writing skills. While studying piano, the artist had early epiphanies and found himself finishing several songs at a very young age. His parents supported him in building an artistic career. “From the day I wrote my first song, I haven’t stopped.” Nourished by experiences, especially family ones, he managed to interpret feelings like love, loneliness, and death, eventually completing first demos. “I never thought of anything else. Suddenly, by a stroke of luck, there came a day when I was heard by someone. And that’s why I’m here today, I guess.”

As we talk about the process of writing songs, Herece tends to get lost in the answers. He claims that his only formula for song-making is honesty. “I don’t know what a good or a bad lyric is, but I know when it’s not honest,” he explains. And that has to do with the fact that a great deal of his lyrics portray the reality of his experiences and that he finds melody in simplicity. However, reading all his songs’ lyrics, it is clear they fulfill their purpose. “I guess the hard thing about writing a song is everything you have to detach yourself from,” he explains, biting a fingernail. “It’s like a stone, and you’re whittling away until you find what’s really honest.” We talk at length about how important it is to feel that an artist is true to himself. “The only thing I’d like is to hear my voice and know I’m not lying to myself,” he says humbly.

When I listened to him for the first time, artists like Luis Alberto Spinetta or Bob Dylan came to my mind, because of the honesty of his storytelling, but also for his melancholic sound and poetic overtures. He grew up listening to Dylan and Joni Mitchell, whom he defines as “artists who make you feel that art is easy.”

On his desk, Herce has a book of poems by Charles Bukowski, who he describes as a natural writer:

“[His poetry] is very quotidian. Suddenly, if I let my guard down, he hits me with something; I love that, the surprise. Sometimes it’s very hard for us to move on to that simplicity.”

Herce’s artistic development was always accompanied by literature. His mother’s influence was essential during his creative process. He recalls being curious, at a very young age, about a book by Gabriel García Márquez which had the word “whores” on the cover. He had always wanted to read it, and “when I was finally able to,” he tells me, “I did it in a single night.”

Some of his compositions make a direct reference to death, “going where Heaven burns,” as one song says. He claims with both certainty and uncertainty, “I’m terrified of dying.” While he was writing his debut album, Balboa, two people very close to him died, and it’s from that place of sadness that “Quiero Sentirlo Todo’” was born. It’s a song that defines the sound of folk in Spanish for the next decade. “Life doesn’t exist without death, just as to write a love song you have to know loneliness,” he says.

Jesús Soto Fuentes for Rolling Stone Español

IT’S ALMOST 8 P.M., and Herce is in Colombian singer-songwriter Santiago Cruz’s dressing room minutes before going onstage. It’s a treat to see two generations of singer-songwriters discussing and remembering songs that complement each other. “His voice has the sensitivity of an old soul,” Santiago says.

A few days ago they began discussing which songs they would sing together: “Did you know that his first single is over six minutes long? Arath is someone who takes the risk of showing us what he wants to say, in his own way. He truly moves us,” Cruz says.

Balboa became an exercise of fresh new folk songs that Herce recorded in Los Angeles, co-produced alongside Aureo Baqueiro. “It was me and him, plus a bunch of incredible musicians.” The album was recorded partially live. He then traveled to London to finish the remaining songs with Jake Josling in a totally different technical process in which he got to be a multi-instrumentalist. “I feel that from the moment I wrote those songs I knew what I needed. I can actually say it was pretty clear. I was lucky that Aureo and Jake let me play; I’m very grateful for that.”

For Herce, his goal is to create songs that last forever. He is not really interested in making songs for a generation or to follow a trend. “I guess I can only be myself,” he says. “A lot of songs were born out of the need to connect with myself first.” He tries to stay true to the real reason he’s an artist; the music will always come first for him. “I keep my songs like a diary. I hope I can look back and remember what I was going through.”

A few moments have already felt like big achievements for himl. He fondly remembers when Leonel García listened to his songs and when Natalia Lafourcade gave him her personal and artistic support. Herce recalls showing all his songs to Lafourcade before going into the studio. “That day she played me some voice notes of De todas las flores on her phone,” he recalls, thrilled Lafourcade would be the first person to hear this demos. “I felt so uncertain and insecure, even though I was so clear about what I wanted. I feel like my head would have played against me if I was all alone.” Upon hearing the songs, she suggested he should work with Leif Vollebekk.

The album is a statement of artistic principles and an ode to live analog music. Co-produced by Vollebeck and recorded live in the city of Los Angeles, it features an unmatched group of musicians. Jay Bellerose (Robert Plant, Elton John, Regina Spektor) and Jim Keltner (John Lennon, George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, Tom Petty) took charge of the drums, and the double bass ended up in the hands of Tony Garnier (Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Tom Waits). “They are musicians I greatly admire. I will never forget this journey,” Herce says.

After recording Balboa, Herce released a solo version of the same album, Balboa Naked, another version of the same songs performed only by him. “Songs are like photographs, and they get old,” he notes. That’s why he had the need to reconnect with his songs in their rawest form, as they were first born, in his room alone only with his guitar and voice. Meanwhile, he’s in a constant process of writing, searching for inspiration to connect with new stories. “Maybe I’ll talk more about death this time. Death and hope,” Herce entices. “I fell in love after a long time, and it’s also about reopening myself to that.” It makes sense that Herce, at his young age, is going through constant growth and change. “My music will change in the same way as I do. This is my story and it’s my life, it’s all I can do.”

Jesús Soto Fuentes for Rolling Stone Español

However, he understands that he faces pressure from a cutthroat market that demands numbers and seeks audience growth on TikTok. “As I was telling you, my real goal is to write and make something that lives up to my heroes.” He’s aware that eventually the years will go by and any success can fade away. But he prefers to be recognized and judged by his work. “Once I die, I would love to know what I became.”