Ronald Reagan knew television. Broadcasting since the birth of the medium, he always understood exactly how he looked on the other side of the camera. He used TV to cast himself as a kindly septuagenarian who loved jelly beans and playing cowboy, while his aides prepped him not with foreign policy debriefings but by telling him what to do in a particular “scene.” His major political battles were waged by the combined force of law and the mass media against enemies foreign (the Soviet Union) and domestic (the poor, especially Black).

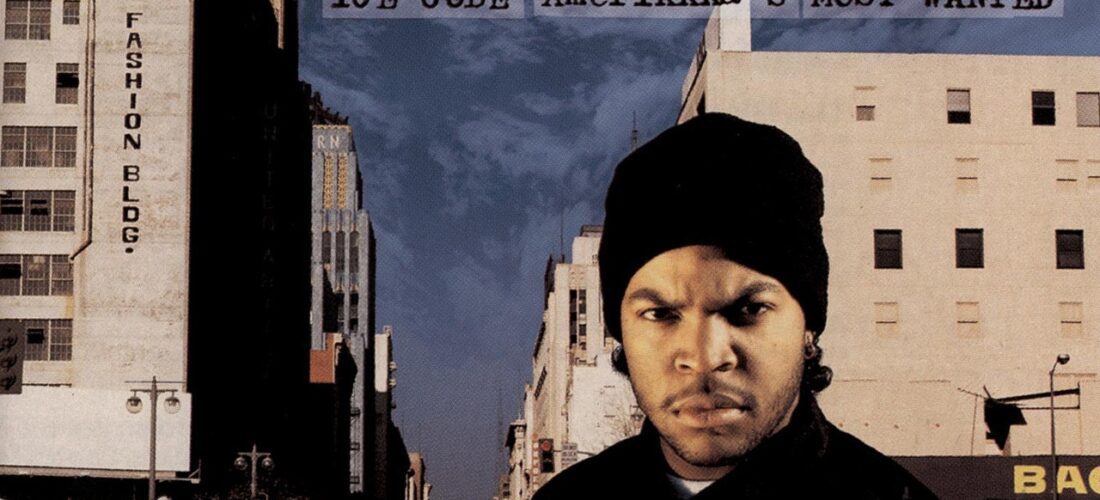

Throughout the decade, a credulous, ratings-hungry TV news media used Reagan’s “law and order” style of right-wing governance to cast young Black men as the nation’s primary criminal menace, known mainly by their Action News poses, described by Ice Cube on “Rollin’ Wit the Lench Mob”: “On my knees in the street /Interlock my hands and feet.” Los Angeles made a great staging ground for Reagan’s so-called war on drugs, and in 1989 the hardline, media-savvy LAPD Chief Daryl Gates invited Nancy Reagan (and a phalanx of TV reporters) to observe a staged raid on a suspected dealer. “The working press arrived to find Mrs. Reagan and Gates munching fruit salad in an air-conditioned motor home parked beside the alleged rock house,” reported the L.A. Times.

By the early 1980s, television had replaced the daily newspaper as the nation’s primary news medium. Increasingly, the cultural relevance or accepted truth of an event was only fully acknowledged once video surfaced on the nightly news, or an evening TV drama ripped the story from the headlines. TV’s unique capacity to absorb, juxtapose, and regurgitate current events through pre-existing genres and cutting-edge visuals would soon come to be characterized as “postmodern,” but a more useful term came from critic Todd Gitlin, who described ’80s TV programming as the ultimate “recombinant” platform. Writing in 1983 of TV shows and films mimicking the increasingly torrid pace of Reagan’s unregulated late-capitalist consumerism, Gitlin explained that “in a world stripped of transcendent unities, the strategy of collage, of juxtaposition, makes the best of a bad situation,” in which “order can be assembled only from the juxtaposition of shards.”

Pop music had been juxtaposing shards into new forms for decades by this point, and no form was doing so more virtuosically than hip-hop, whether via DJs looping rhythmic breaks or rappers adopting outlandish personae and shuffling through pop culture references. As hip-hop became more political, rappers started mimicking the news reporters who were constantly prowling around their neighborhoods. In 1982, Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five’s “The Message” opened with Melle Mel braying a tabloid headline about the shards he saw all around him: “Broken glass, everywhere!” A year later, Run-D.M.C. debuted with their own form of recombinant street journalism by flipping Walter Cronkite’s epochal and confident CBS Evening News signoff—“And that’s the way it is”—to a mordant slogan for young Black no-hopers at the dawn of Reaganism: “It’s like that/And that’s the way it is.” A few years later, Public Enemy frontman Chuck D—who was born in 1960 and came of age during the peaks of Black Power and 1970s Black television—took the metaphor to its logical conclusion, telling Spin that “rap is Black America’s TV station,” a medium that “gives a whole perspective of what exists and what Black life is about.”