How does one arrive at nihilism? It can’t be the origin point of a belief system. Surely there was light along the way. Was it hope dashed, snubbed out like a cigarette on the sole of a boot, that caused the black veil of ennui to lower? Or could it be that societal abnegation is a direct cause of listening to too much Flipper, the Bay Area punk band who in the 1980s took potshots at mindless happiness with their nonstop morose couplets? “Ever wish the human race didn’t exist,” begins one of the rhetorical questions posed in their song “Ever,” “and then realize you’re one too?” Quite frankly no, I hadn’t, until you brought it up.

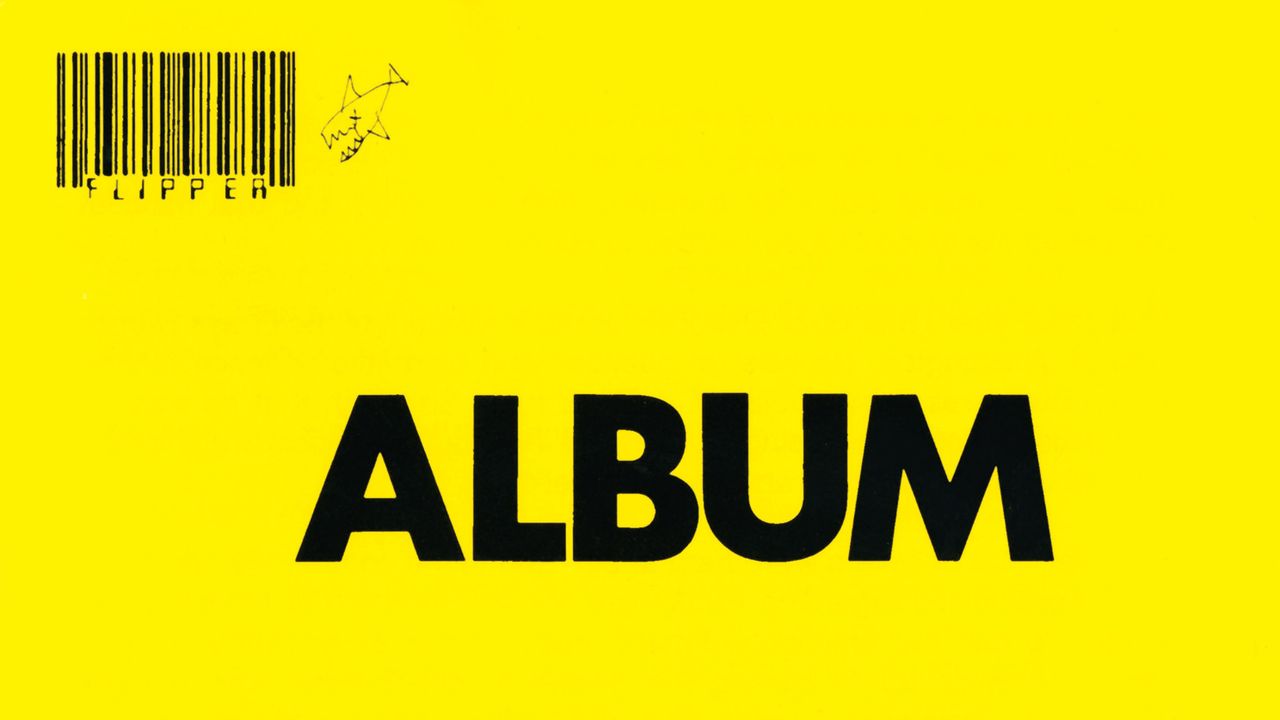

“Ever” is the first song on Flipper’s 1982 debut, Album – Generic Flipper, and it’s a doozy. In three short minutes, vocalist Bruce Loose (formerly Lose; he added the extra “o” later in an attempt to be less of a bummer) spews a series of scenarios that make it clear he wouldn’t be too much fun on a first date. “Ever live a life that’s real, full of zest, but no appeal?” “Ever play the fool and find out that you’re worse?” “Ever look at a flower and hate it?” It feels like Anne Sexton wrote a children’s book.

Flipper’s music is correspondingly off-putting. The band members were ostensibly punks but avowed fans of the Grateful Dead. The blend of those jammy instincts with punk attitude is surreal and often weirdly dazzling. On “Ever,” the downbeats and handclaps are like something out of a Frankie Avalon movie, but it’s not beach music, unless a typhoon looms. Ted Falconi, on guitar, sounds like a drunk trying to play a Buddy Holly song. Drummer Steve DePace keeps time, barely. Loose has a depraved yelp whose disgust subsides only at the song’s end. “Well, have you?” he says. “I have,” he answers, with a touch of shame. And the echoed rejoinder: “So what.”

The song makes a solid case that the world’s gone rotten, but instead of offering resistance or condolence, it gives you a wedgie. Still, it’s that final phrase that gets you: So what… After all the buildup, after all the flowers and ugliness, nothing really matters anyway. Those two flippant words get to the core question at heart of Album – Generic Flipper: Is it better to have hope and be disappointed or not to care in the first place?

Flipper formed in San Francisco in 1979, a time when punk was bleeding into hardcore, and Jimmy Carter was losing reelection. The American underground had anger on its mind; indifference was uncommon. The puckishness of punk, a snotty new genre that had grown out of rock a decade earlier, was beginning to evolve into hardcore, a steelier genre, with more fury and less fun. Originators on both coasts ripped through songs in two or three minutes, vocalists yelling invectives, while the drums marched along, unsettled. Minor Threat, Washington, D.C. hardcore originators, had vicious and obstinate songs like “Screaming at a Wall,” “I Don’t Wanna Hear It,” and “Seeing Red.” Los Angeles’ Black Flag had “Nervous Breakdown,” “Life of Pain,” “Thirsty and Miserable,” and “Depression.” It was impassioned music, and listening could be cathartic, if not exactly joyful.